By Alyssa Martino

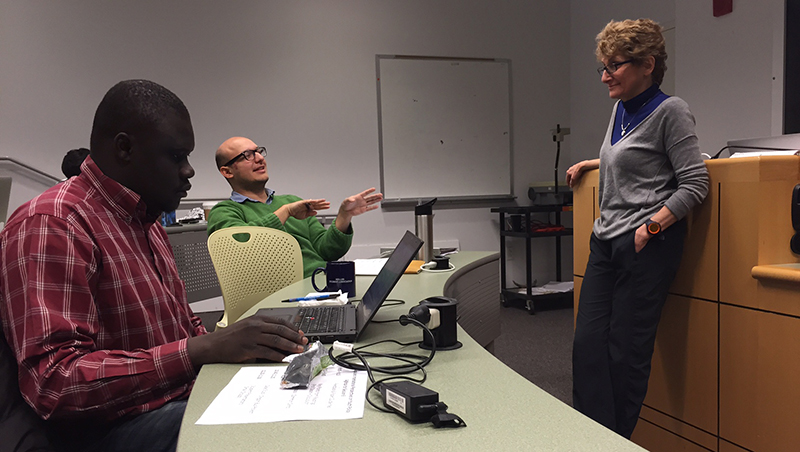

Professor Joan Dassin '69 talks with students in class.

Thirty students stare at a large projector screen in the front of a classroom, mesmerized by a man with red hair nearly 3,000 miles away. He’s Jefferson Smith, founder of The Oregon Bus Project, a project in hands-on democracy. Today, he woke up early to video chat with students in Professor Joan Dassin ’69’s seven-week class, “National and International Perspectives on Youth Policy and Programs.”

Smith flashes a sudden grin and confesses, “I’m wearing my Superman pajama bottoms.” He points his laptop camera at his pant leg to show off the tiny red-caped heroes. Laughter erupts throughout the classroom. “But that’s not because I don’t take this subject matter seriously,” he adds.

The course is part of Heller’s Master's Program in Sustainable International Development (SID)—a program that Dassin took over last fall as director and professor of international education and development. Dassin returned to her undergraduate alma mater after working as the founding executive director of the Ford Foundation’s International Fellowships Program, which operated from 2000-2013. In this role, she oversaw thousands of scholarships for social justice leaders to study abroad at the graduate level. Over 150 of the fellows studied at SID. Dassin also previously directed the Ford Foundation’s Rio de Janeiro office and Latin American programs, and has received three Fulbright Scholar Awards for research and teaching in Brazil.

But why teach a class on global youth policy in 2015? Dassin says the necessity is rooted in recent demographic trends. Today, there are more than 1.8 billion young people between the ages of 10-24, according to the United Nations Population Fund. That’s more youth than ever before. “Because the fertility rate has declined everywhere in the world, there are fewer children coming behind the group of young people born before those drops occurred,” Dassin explains. “So, what has been created is called the youth bulge.”

The young people in this “bulge” often live in developing countries, she says. In fact, nine out of ten of them currently live in conditions of poverty. “The question of poverty and the question of youth are inextricably linked,” says Dassin, “which means that, by definition, youth is a development question.”

That’s why Dassin has arranged many class meetings around one or more guest speakers who connect with students from as close by as Manhattan and as far away as Kenya. Many activists, policymakers, and researchers recognize the importance of addressing issues related to youth. Fortunately, technology advances like video chatting have made sessions like today’s with Smith possible.

Between cracking jokes, Smith notes that 80 percent of the U.S. budget is spent on Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid, the military and national debt service. “Which of those things serves your generation?” he asks, pointing toward students. “Most of that stuff is not for young people.”

After attending Harvard Law School and watching the country’s post-9/11 evolution, Smith grew interested in public service—particularly in the way face-to-face contact can motivate voter engagement. So, he took the obvious next steps: he bought a bus and filled it with young activists who knocked on 70,000 doors to discuss local state senate elections in Oregon. Now, the Oregon Bus Project has developed into a national, nonprofit, nonpartisan federation, with seven headquarters around the country.

But Smith’s focus—civics and youth engagement—is just one of four policy areas the class has tackled over its time together. Others key topics include employment, education, civic engagement, and avoiding risky behaviors and violence, all of which are critical to the advancement of young people.

Dassin says that many students have career or volunteer experience in one of those areas, which may be why the class energy level seems so high. Hands shoot up eagerly when Smith says he is available to answer a few questions.

“Every single person in this class is really passionate about youth,” says Rodrigo Moran, a first-year in the SID program. “I decided to take the class because I worked in youth policy for six years.” Moran’s experience includes working on a United States Agency for International Development (USAID)-funded project in El Salvador’s capital, San Salvador. “What we did was create a movement of youth in San Salvador, tired of the situation of violence,” says Moran, “who wanted to propose a set of recommendations to the Salvadorian government in order to have a national violence prevention policy.”

Moran says he was also enthusiastic about working with Dassin because of her Ford Foundation background, as well as the “international cohort that comprises the class.” Lisette Anzoategui, a second year SID/Coexistence and Conflict Master's candidate, agrees: “What surprised me about the course is the remarkable collective knowledge and experience our class was able to build based on our diverse experiences in youth development.” She adds that, “in one single classroom space, we are able to discuss the relevancy of vocational educational training for social mobility in Kigali, San Salvador, Juba or in my hometown, Los Angeles.”

Dassin says the class, just like the SID program, is extremely diverse, with students from all over the world bringing a wide range of experiences working with youth. In fact, the topic is so popular that several students audited the course.

One reason for this may be the international focus. “I’ve tried to design a course that’s global in its outlook,” she says. At the same time, she’s taken advantage of deep domestic expertise at Heller, inviting Professor Susan Curnan and Della Hughes of the Center for Youth and Communities (CYC) to share the center’s work in youth development, education, and employment in the U.S. with her students (Dassin was invited to take over the course by Professor Andy Hahn, who co-founded the CYC with Curnan and recently retired as director of the Sillerman Center for the Advancement of Philanthropy).

At the end of the video chat, Smith shares a quote he once heard: “We are not put on this planet to do everything. We are put on it to do something.” His expression grows more serious. “The accomplishments of the bus project aren’t everything, but they are something.”

Dassin hopes students will be inspired in her classroom—both by the passion and drive of guest speakers, and by each other. “In my view the SID program isn’t only about providing students with training for good jobs in the development sector,” she says. “What it’s really about is how to understand and shape key policy areas such as youth employment, education and civic engagement in order to drive social change, both in the U.S. and in developing countries.”