This September marks the conclusion of a four-year joint venture between Heller’s Institute on Assets and Social Policy (IASP) and New Hampshire’s Office of Minority Health and Refugee Affairs (OMHRA) to strengthen the diversity of the state’s healthcare workforce. As the patient population of New Hampshire grows increasingly diverse, the state strives to mirror that diversity among healthcare workers as well.

Throughout the Healthcare Employer Research Initiative, principal investigator Janet Boguslaw and co-investigator Sandra Venner have helped New Hampshire employers and other stakeholders improve the hiring, retention and advancement of its minority healthcare workers. This partnership, funded by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families, seeks to understand the role that job training and workplace practices have in advancing the racial, ethnic, and linguistic diversity of the healthcare workforce.

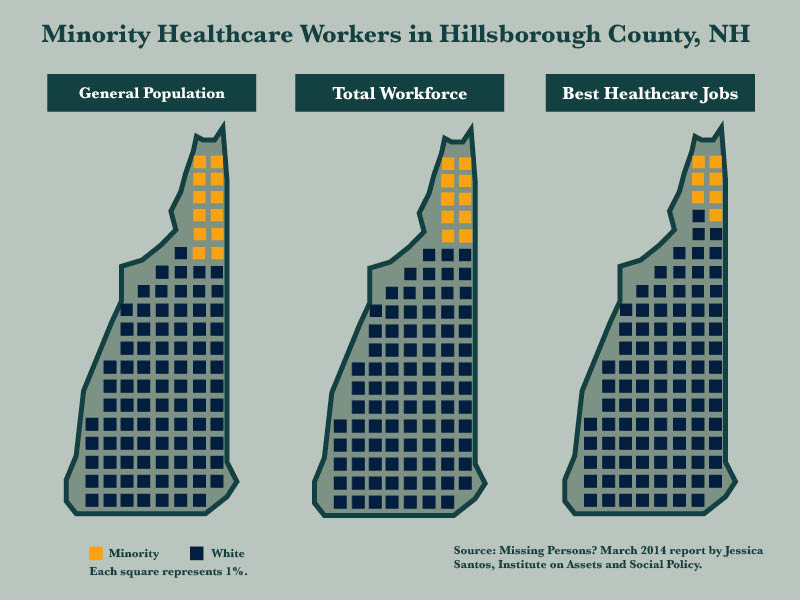

OMHRA explicitly seeks to enroll 25 percent minority trainees in its program. While the minority population of New Hampshire is just 8 percent, Nashua and Manchester—New Hampshire’s two largest cities—are more diverse, with minority populations of approximately 20 percent. Despite these rising figures, minority workers in Hillsborough County (which includes Nashua and Manchester) account for less than 10 percent of the total workforce, reflecting the youth of this population and its growing prominence as the workforce of the future.

However, the long-term objective of OMHRA’s work goes beyond just getting minority workers into the healthcare field. Through their work with the IASP team, they intend to sculpt an industry culture that promotes equitable inclusion, retention and promotion of minority healthcare workers at all levels. “For example, minority healthcare workers are over-represented in the lowest-paying healthcare positions, such as nursing and residential care facilities, and underrepresented in higher-paying positions,” says Venner. White employees are over-represented in hospitals and ambulatory care jobs, which not only pay more—they’re also more stable and offer greater opportunities for promotion.

Janet Boguslaw and Sandra Venner of IASP

Both within and beyond the healthcare sector, racial and linguistic minorities have traditionally been excluded from these desirable jobs as well as the educational pipelines and social networks that facilitate entry to them. “Data shows that there is still high occupational segregation by race,” says Boguslaw. “Since most people utilize their family, community, and school networks to enter the workforce and choose a career path, we need to build workforce development systems and employer practices that are effective in facilitating upward mobility.”

To that end, the IASP team has helped employers and OMHRA reveal barriers to upward mobility for minorities in the healthcare workforce—such as isolation from social and professional networks and experience. To counter these barriers, the team developed simple recommendations, like altering job descriptions, as well as more complex ones, such as fostering professional mentoring and interning programs. Another key focal point is promoting not just employee cultural competence trainings, but true cultural effectiveness at the institutional level through systematic policy changes.

Kris McCracken, director of the Manchester Community Health Center, has embraced cultural effectiveness as a way to improve both the workplace environment and the level of care provided to patients. McCracken says “We are exceedingly grateful for the experience and guidance that the team from IASP has provided as we work to implement a Center of Excellence for Culturally Effective Care. The team has a rare set of skills, and their combined experience in social justice, employment opportunities and challenges for diverse communities, health equity and disparities research and culturally effective organizations is irreplaceable.”

Broadly, this project contributes to the growing literature on the determinants of the racial and ethnic wealth gaps, asserts Boguslaw. “We have to change how institutions function, and the transparency with which they structure opportunity in their organizations,” she says. “Doing so will enable many more employees to have opportunity and equity that doesn’t exist currently. The barriers to opportunity are often very subtle, and employers typically say ‘this is the only way to do business.’ In fact, there are other, better ways to do business that can help improve the well-being of employees and their families, as well as the health of communities and the business itself.”