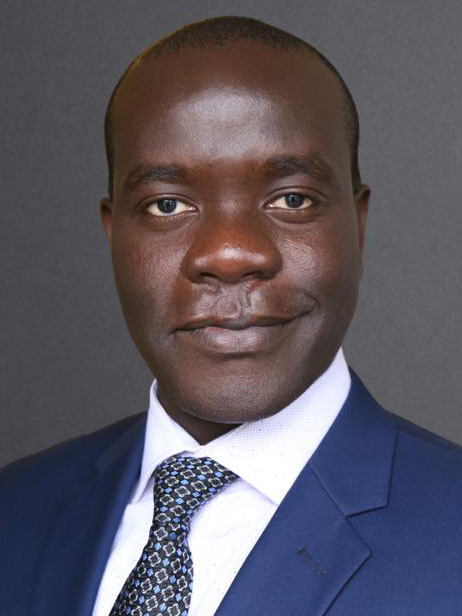

By Sarah C. Baldwin

Growing up in Uganda, Francis Ojok, MA COEX’21, witnessed violent conflict firsthand. In the 1990s, the infamous Ugandan warlord Joseph Kony formed the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) with the goal of overthrowing the government of President Yoweri Museveni. The LRA is notorious for its violence against civilians, including children, thousands of whom have been abducted and forced to become child soldiers.

While he was not a child soldier himself, Ojok did visit the United States on three awareness-raising tours under the auspices of Invisible Children, Inc., a lobbying and advocacy organization that works to disarm, rehabilitate, and reintegrate LRA escapees and help rebuild communities through financial, educational, and mentorship support.

Heller Magazine spoke with Ojok about Heller’s MA in Conflict Resolution and Coexistence program (which, in fall 2024, converged with the Sustainable International Development program to form the MA in Global Sustainability Policy and Management) and how it aligns with and informs his work.

What made you want to pursue a career in dispute resolution and peaceful coexistence?

As a child, my life was characterized by losing people. Many of my peers were abducted and forced to be child soldiers. My family was forced into a displacement camp. Even there, we were not safe from attacks by the rebels as well as, sometimes, government soldiers. Growing up, I wanted to become a priest. My intention was to spread the gospel of love and forgiveness, and through that be able to create an impact on my community.

But as I grew older, I thought, I don’t have to wait for people to come to church to do that. I decided the most effective tool I could use to bring change to my community was law. So I went to law school and then worked as an associate in a private law firm in Kampala. But at the firm, I realized that everything I was doing was contrary to why I went to law school in the first place: to be the voice for my community. As a lawyer I was trained to look at a situation from either point A or point B. There was nothing in between. I realized that a solution based on either-or does not guarantee peaceful coexistence in the community. Because even if party A wins a case in court, party B loses, and they still have to go back [to their community] and live together.

That is when I started asking myself, “What about those things between A and B? How can I use the law to look for solutions that are not handed down to the parties by the judge, but are arrived at by the parties themselves?”

What made you choose to attend the MA COEX program at Heller?

In Kampala, I started an NGO called Kuponya Peace and Justice Initiative, which works to create peaceful coexistence between the modern justice mechanism and the traditional justice practices that have been in Uganda for generations. Traditional justice is entirely based on reconciliation, on creating a peaceful end.

Uganda is home to more than 1.5 million refugees. And it is a developing country itself, suffering from high population growth. Because of the high numbers of refugees and limited resources, there have been clashes between the refugees and the host communities. I realized I needed new tools and skills to carry out Kuponya Peace and Justice Initiative’s mission.

I learned about the Heller School’s MA COEX program through an associate at Invisible Children. I researched it and noted that Professor Pamina Firchow had done work in Uganda, and Professor Alain Lempereur [the Alan B. Slifka Professor of Conflict Resolution and Coexistence] had done work in East Africa. I also appreciated the diversity of the program. I'm the only person in my family to not only attain this level of education, but to travel outside of my village. Seeing that the COEX program includes so many international students, I felt that even if I’m away from home, I will have a new community, a community convening around service learning and living a life of purpose.

In addition to running the nonprofit, you also founded and are CEO of a business in Washington. What is it?

In 2023, when I moved to the District of Columbia, I asked myself, “Now that this is the place I call home, how can I use my skills to contribute to making it better?” That led me to found DC Mediation and Dispute Resolution Institute. Our goals are to prevent, resolve, and transform conflict. We offer mediation services, but we also provide training, with the goal of enabling anyone to become a change maker in their community. Impact is like a puzzle, where you add your piece, the other person adds a piece, and the next person adds theirs. Collectively we can all bring our pieces together and make a holistic impact in the community.

You also do family mediation in D.C. Superior Court. Why?

I do family mediation simply because I never had parents in my life. My hope is that I can use my skills so children caught up in family disputes never have to choose to go with the mother or to go with the father. There is nothing that I find more fulfilling than watching parents walk into my mediation when they’re not talking and seeing them smiling when they leave. That is the most rewarding thing ever.

What are some takeaways from the COEX program?

Uganda is a very diverse country. Professor Ted Johnson [former director of the COEX program] taught me critical approaches to diversity.

Another class was Responsible Negotiation with Professor Alain. During the debrief after a negotiation simulation, he said, “You may get everything you want, but is that the best solution?” He introduced the idea of putting yourself in your counterpart’s shoes, of looking beyond what you want. That was the first time I heard that notion. It’s not something I was trained to do. In law school, you’re trained to represent your client. It’s a concept that now guides my interactions on a daily basis. I strive to look at the world not from just my viewpoint, but from other people’s perspectives.

Heller also gave me the opportunity of sitting in class with people from all over Africa, every part of the globe, and learning to embrace every individual. It made me appreciate the uniqueness of every human being. That guides my work, at both the personal and professional levels.

What do you wish people understood about mediation?

A lot of people have no idea what mediation is. I don’t blame them! I spent years in law school, but I only took a few hours of mediation. Mediation is the most effective tool if people truly utilize it well. Conflict generates emotion, and when emotion takes over, we stop reasoning. When we stop reasoning, we stop listening. And when we stop listening, we’re just reacting. We think, “What can I do to this person?” rather than, “What can we do?”

In mediation, sometimes the disputing parties are sitting and truly talking for the first time. Through effective facilitation they’re able to hear each other, see each other for the first time. Even if they fail to reach an agreement, they know where each other is coming from. That clarity alone is a huge success.

Where do your positivity and resilience come from?

When I was growing up, my environment gave me two options — to accept the war, the violence, the killing as a norm, or to transform my anger into a positive force I could use to make a difference. I chose the latter. People are not as bad as we think. I have seen the goodness and the badness in people, and the goodness always outweighs the bad.

When I was working at the law firm in Uganda, we represented one of the leaders of the rebel group that terrorized my community. As a junior associate, I was assigned to his case. I had to go visit him at the prison. It was a difficult thing for me to sit in a small room with him, face to face, knowing that he was directly responsible for attacking my village. But I felt, “If I hold onto that, it means he has the keys to my happiness, to my healing.” I chose to heal — to take back the keys to my happiness. Even though he did not show any sign of remorse, I was able to visit him and provide him with the best legal services I could.

Growing up, I lost everything and there was nothing more to lose. I only had one thing: From here, what can I give as opposed to what can I gain?