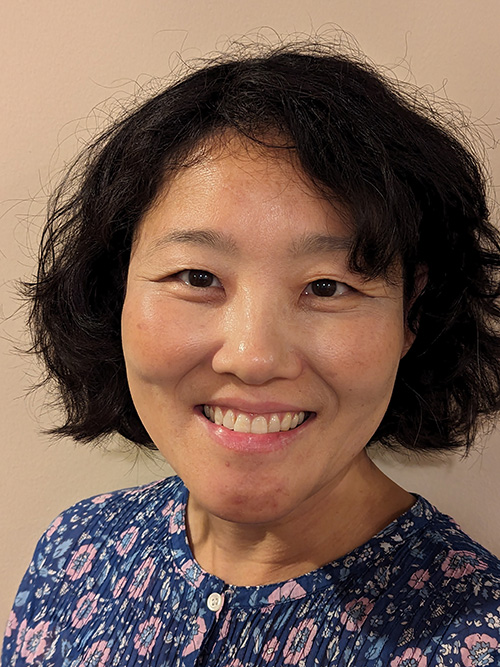

Meelee Kim, PhD’19, is a scientist in the Institute for Behavioral Health (IBH) at Heller. With nearly two decades of experience conducting research and evaluation using mixed methods, she applies a participatory action research approach when working with community-based organizations and other community stakeholders. In 2023, she received Heller’s Early Career Research Investigator Award for her work in communities with underserved populations to reduce the impact of alcohol, drug, and mental health problems, as well as building supports for youth and young adult populations.

Tell me about your research.

I’ve worked with communities to enhance services for underserved populations on a wide range of issues and research topics, including substance use and addiction, prescription drug misuse, recovery supports, health information systems, HIV prevention, homelessness, and trauma-informed services. For me, it’s more about partnerships with community-based organizations, letting them determine what the priority areas are at the moment, and working with them to identify community-based practices, or curricula, or policies that would have the best odds at addressing those issues.

The work I do is never done alone. I’ve got a team of people I work with on a day-to-day basis that includes people outside of Heller. Sometimes I hear from community members that they’ve worked with researchers who come into their community with good intentions and great study designs, but after the scientists collect their data, they disappear and there’s not much time and space to engage in the process. While the research topic and the work itself is important, I also try to focus on the process of engaging with community stakeholders and staying connected as much as possible, even after the grant is completed.

How did you first get interested in this area of research?

My first entrance into the world of social services was working in a soup kitchen when I was in high school, and then I spent a few years working as an advocate in a homeless shelter for women. Like many frontline staff, I got burned out, but I didn’t want to leave the field. I got involved with a consulting agency in Boston that Mary Brolin [a senior scientist with IBH] was a part of, and that’s where my career in research and evaluation began.

I’ve had the privilege of working on a wide range of issues and interventions at the national, state, and local levels. While they’re all equally important, I find more excitement and engagement working as closely as possible with the population that is being served. Learning directly from them helps me as a researcher have a greater appreciation for the impact these programs and policies have.

How can communities support youth and young adult populations?

The pandemic has really highlighted some crisis-level needs. The isolation and the disruption in their everyday routines has magnified the need for behavioral health services, and while there are a lot more resources now through federal grants to increase services and [provide] easier access, there is also a real workforce shortage issue in the behavioral health field. However, communities have many ways to increase protective factors for youth development, like a sense of belonging, reliable support systems, and opportunities for positive social engagement. Youth are extremely resilient and creative, and sometimes adults in communities miss opportunities because they don’t know how to collaborate with and empower them. I think at some level, we have to go back to the basics and learn how to listen and respond respectfully to their ideas, and seek out those youth who don’t typically engage in school activities.

What’s something you’d like policymakers to understand?

I think this is a [societal] issue, but policymakers need to be a little more trusting of the research and take a more comprehensive view of problems. For example, regarding the issue of opioids, for several years policymakers were really focused on overdose deaths as the metric to address. While I absolutely agree that it is critical to prevent deaths, there wasn’t enough attention paid to primary prevention for all kids and secondary prevention for kids who are already identified as being at risk.

If you can’t get to the primary prevention work, you’re just constantly in this battle of using a Band-Aid on a critical problem. So while I appreciate that policymakers don’t have time to wait for the final results of a multiyear research study, they can still be data-driven and look at root causes to inform a more comprehensive approach for creating policies.