By Karen Shih

Protestors took to the streets in 2020 for racial justice and police reform. The Black Lives Matter movement turned the nation’s attention to the brutal deaths of Black citizens like Breonna Taylor and George Floyd at the hands of law enforcement. Calls to “defund the police” became a rallying cry as activists and policy experts began reimagining community safety and proposed redistributing resources from law enforcement to social services.

This push for change isn’t new. In every era of American history, from slavery to Jim Crow to the Civil Rights Movement, Black Americans have been challenged by law enforcement as they’ve fought for equal rights. In recent decades, police departments have grown increasingly powerful, backed by racist policies like the Nixon-era “War on Drugs” and 1994 crime bill, and have gained military-grade weaponry. Today, the ubiquity of smartphones and social media has increasingly brought acts of police brutality to light.

So how can the protests of 2020 spur tangible action? Transforming the system requires the ongoing work of individuals and organizations on the ground, including the efforts of Heller students and alumni who have dedicated their lives and careers to racial equity and police accountability. Today, they’re harnessing the energy of the movement to advance important policies and programs.

Kelcey Duggan, MPP’18, is empowering local leaders across the country with the research and tools to hold police accountable and redistribute resources. Brenda Bond-Fortier, PhD’06, is using years of research and firsthand experience in a police department to create organizational change. And PhD student Christian Bijoux is training police departments across the country to confront racial bias and change mindsets, as well as changing outcomes for system-involved youth.

“We have to use this moment and opportunity wisely and effectively and present radical solutions,” Bijoux says. “Ordinary solutions cannot work to solve wicked problems.”

Promising new efforts

Across the country, local leaders are starting to reevaluate the role of police in their communities—thanks in part to the Community Resource Hub for Safety and Accountability (“the Hub”) in Philadelphia, where Kelcey Duggan, MPP’18, works as a research and policy associate.

“We’re empowering city council members to make decisions and give them proof that you can do something else other than increasing the police budget,” she says, providing them with research, toolkits, and model policies and legislation to reform policing and enhance community safety measures. “It’s still a new situation, but there have been some relatively promising efforts.”

Since the protests started, cities like Seattle, Austin, Texas, and Berkeley, California have cut their police budgets. Berkeley even took it a step further, creating a new traffic enforcement agency to remove police from traffic stops—an innovative new step that could save the lives of Black drivers, who are pulled over 20% more than white drivers, according to the Stanford Open Policing Project.

But while redirecting funding is a good first step, there’s more to do, Duggan says, especially as the COVID-19 pandemic puts pressure on underserved populations, especially those of color. “There’s still a struggle to get cities to meaningfully reinvest in needed community resources like housing assistance, especially as we see eviction moratoriums run out, childcare services, unemployment assistance and more.”

Duggan started her career with the parole board of Florida, but quickly “realized I wasn’t on the right side of what I wanted to do. I wanted to help work toward more change in the criminal justice system, rather than perpetuate it.”

That’s what led her to Heller for graduate school, where she focused her Master of Public Policy studies on Black women and LGBTQ people in the criminal justice system, and to work for the Hub after graduating. Today, she’s using her research and writing skills to address issues like police unions, which remain powerful obstacles to major change in law enforcement. (Read full Q&A about Duggan's work.)

“We’re strengthening civilians’ understanding of how police unions operate,” she says. Locally, she’s providing support for efforts to amend Pennsylvania Act 111, which gives the police union power to undo disciplinary action and keep officers on the job after incidents of police brutality. Advocates using the Hub’s resources have also pushed the Philadelphia mayor and city council to hold a public hearing before finalizing a new police union contract, giving the community a voice in the process for the first time.

Another research area is the use of surveillance technology in law enforcement, a major project Duggan recently wrapped up with the Action Center on Race and the Economy.

“Surveillance has been used to track down people by their faces, the clothes they wear, the tattoos they have, their license plates, to then arrest them and keep them in jail on excessive charges. That’s something that poses a major concern for First Amendment rights and due process rights,” she says. These technologies can also be racially biased and rely on mugshot databases that have disproportionately more Black and brown faces.

The Hub Director Hiram Rivera says, “Kelcey’s role at the Hub has been vital to the technical assistance we provide frontline organizations working on policing accountability and police transformation campaigns across the country. There’s no question that the success of the Hub’s work nationally is due in great part to the work Kelcey has provided.”

Duggan is cautiously optimistic that continued activism from community members, advocates and organizations can keep cities moving in the right direction.

“Each setback still has bits of progress in it, and with the pandemic and the wealth and racial inequality in this country being pushed to the forefront once again, coupled with the continued police brutality that spurred this current Defund movement, I think change is coming. And it will likely start on the local, city level, which is where people can have great power when they organize and commit to justice.”

A roadmap for change

While many working on police reform have an outsider’s view, Brenda Bond-Fortier, PhD’06, has an unusual vantage point. She worked for seven years as director of research and development at the Lowell Police Department in Lowell, Massachusetts before coming to Heller to earn her PhD.

That gave her a first-hand look at how to implement new ideas to build community relationships and improve performance management systems in a police agency. In early 2020, she released the book, “Organizational Change in an Urban Police Department,” based on her work in Lowell as well as her research as a professor at Suffolk University’s Institute for Public Service.

“When you look at the research around reforming policing and criminal justice, it is usually focused on what works to reduce crime,” she says. “What I see in the current debate around reform is it really is laser-focused on the institution and how it’s constructed in a way that creates conflict and tension between communities of color and police agencies.”

To begin to address these tensions, police departments must invest time in community conversations to understand different perspectives on public safety, especially from Black, immigrant and other marginalized populations.

“You can’t impose on a community what you think safety is,” she says.

She uses this approach in her work as a consultant for police departments across the country, working to redefine public safety. (She’s currently consulting for Brandeis as the university searches for a new director of public safety and chief of police.)

The problem with the current policing system, Bond-Fortier says, is that it relies on measures of safety that don’t accurately reflect community priorities. The 18,000 police agencies across the country largely rely on the Uniform Crime Reporting Program and the National Incident-Based Reporting System. They track particular types of crime, such as homicide, robbery, rape, aggravated assault and property crimes.

“But these measures don’t capture community perceptions of safety, such as if someone doesn’t feel safe walking in a neighborhood because there aren’t any street lights.” she says. It misses out big questions like, “Will I call the police? Do I trust the police?”

To effectively increase community safety, police can only be one part of the equation.

“The police have become the 24/7 response for every emergency, including things like mental health challenges, opioid addiction, homelessness,” she says, but resources should be redistributed to the service providers who are best suited to respond, such as mental health clinicians.

Local government leaders must bring together schools, agencies, nonprofits and business leaders to more comprehensively address community issues, Bond-Fortier says. Through a formalized structure like a memorandum of understanding (MOU), leaders can commit partners to working together and sharing data.

“These formal structures can help outlive political cycles,” which are one of the biggest obstacles to lasting change, she says. “With the MOU set up, it’s harder for a new leader to come in and dismantle it.”

Using this model of local leadership and inter-agency cooperation, Bond-Fortier believes the issues of institutional racism and police brutality can begin to be addressed.

“What we’re seeing now is some real political will to face that reality that has not been taken seriously before, prompted by videos and technology and evidence that there are patterns across institutions,” she says. “We have to change policing. But it can’t be in isolation of what happens in other areas of local policy, such as housing, employment and education.”

“Racism is a virus”

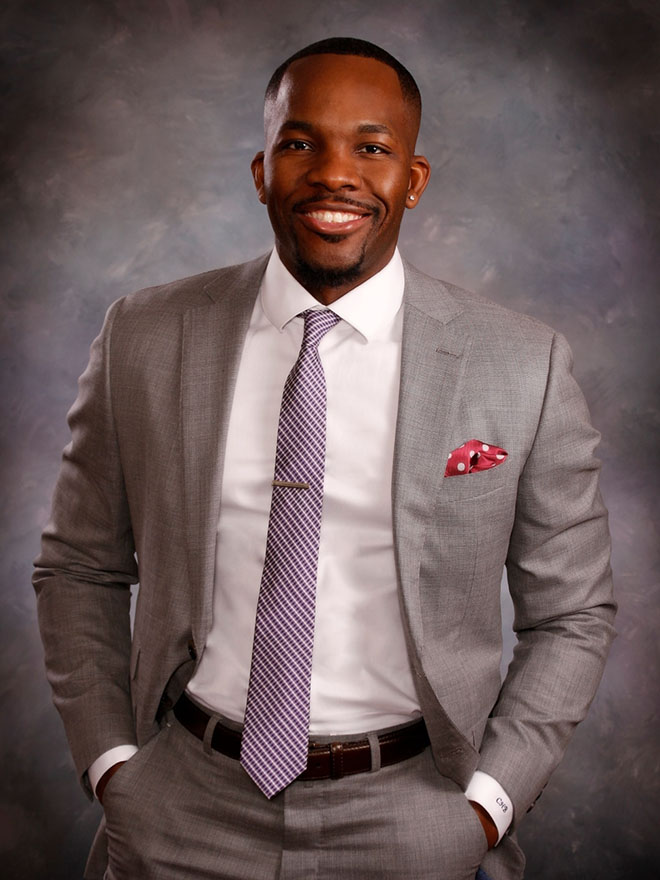

“In the Black community, we’ve always experienced police injustice, educational and healthcare disparities and injustice. This has always been our reality and it needs to be addressed with a great sense of urgency,” says PhD student Christian Bijoux, Gerben DeJong and Janice DeJong Fellow.

That’s why he’s been working with police departments across the country for the last five years to address racial bias in law enforcement. He started in 2016, when he was working for the Department of Youth Services in Massachusetts and spoke at a Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI) Conference on addressing disparities in the legal system. Patricia Contente, director of community outreach and help and recovery at the Somerville Police Department, heard his talk and invited him to work with the department’s Crisis Intervention Team for an initial hour-and-a-half session, which turned into ongoing training.

“It’s been incredibly powerful—Chris is skilled. In his model, instead of statistics or big PowerPoint presentations, he uses conversations, where officers can bring up questions,” Contente says. “I’ll be honest, there was pushback. But the positive feedback we received from officers led us to create a two-and-a-half-hour training, and we’re looking to expand further.”

Bijoux’s interactive sessions include having the officers role-play as someone in a racially subjugated position.

“Every room I go into is 95% male, and 90% white. There’s a challenge for them to recognize the inherent privilege and enormous power they have,” he says. “But I facilitate it in a way that they know I’m on this journey with them. I give them my personal phone number and email and make myself accessible if they don’t know how to respond to something.”

He’s also been working with police agencies on creating public-facing dashboards that create transparency and build more trust with law enforcement and community members.

“If there’s transparency in the process, if you shared that communication with the community before it’s requested, people will trust the process more,” he says.

In addition to his extensive training work, Bijoux is also committed to creating better outcomes for youth of color who become involved with the police. Today, he is the director for the Dually Involved Youth Initiative in Santa Clara County, California, bringing together the child welfare, juvenile probation, and behavioral health services departments.

“It’s a misnomer to call it the juvenile justice system because it’s anything but a justice system,” he says. “My responsibility is to prevent youth from bouncing from one agency to the next, in order to minimize the collateral effects of the system and help them develop into healthy, productive adults.”

A key component of his work is to identify policies that have harmful consequences and change them or the way they are executed to prevent harm. One such policy is kinship placement, which says that youth should be kept with family members when they transition out of the legal system.

“But what happens when you have a family that doesn’t fit in the traditional definition? Or someone who’s willing to take in the youth but doesn’t have the state-mandated number of rooms or bathrooms? What we deem safe from our privileged lenses is so Euro-centric. Kinship placement is an example of the subtle discrimination in these policies that aren’t at face value written to do harm,” he says.

That’s why organizations and corporations, including police agencies, must upend the traditional hiring model to bring in new voices.

“Do more recruiting and less hiring,” Bijoux says. Simply releasing a job description and giving a basic rubric of education and years of experience immediately limits the applicant pool. “We have to move away from, ‘We can’t find qualified minority applicants.’ They’re not on Mars or in a fairy tale. There are thousands who are extremely qualified—but have you been creating those intentional relationships for them to come into your organization and feel like their voices will be heard and they will truly be seen?”

There are numerous anti-racist frameworks that organizations can adopt, and at Heller, Bijoux is researching for his dissertation which of them is truly effective in changing organizational culture and creating more diverse and equitable internal and external environments.

He urges all who are committed to social justice, including white allies, to put in the effort to advance to a place of true racial inclusion.

“Racism is a virus,” he says. “The trauma is real in the Black and brown community. If you want to be part of the solution, you have to do the work. Don’t perpetuate the status quo. Change your mindset, the policy and the practice. It’s 24/7, every day.”