By Nomi Sofer ’91

Five-year old Cristian loves to dance and play video games – and he’s excited to be back in kindergarten in person after a year of remote schooling. Like many other children in the U.S., Cristian’s parents lost their jobs during the pandemic. His mom, María, is a house cleaner, and his dad, Rafael, is a house painter. COVID-19 caused work for both parents to disappear, and the family quickly fell behind on rent in Hollywood, Florida.

When the CARES Act passed in March 2020, many families celebrated the much-needed relief payments of $1,200 per adult and $500 per child. But Cristian’s family was left out because his dad does not have a Social Security number – even though Cristian and his mother are U.S. citizens.

“The issue of rent has been the toughest.... We do not qualify for the government aid, and for that reason we cannot pay rent,” María explains. “I didn’t decide for the pandemic to come to cause everything to fall apart.” She urges lawmakers to keep families like hers in mind when they make policy: “Think about families. Think about the children. Think about a better future for the country.”

María and Cristian are among the 5.1 million U.S. citizen children and spouses who were excluded from CARES Act stimulus payments designed to help struggling families survive during a pandemic. For the nearly 10 million children in the U.S. living in poverty – 41% of whom are Hispanic children—this exclusion has far-reaching impacts.

That’s why Heller researchers Dolores Acevedo-Garcia, director of the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy (ICYFP), and Pamela Joshi, PhD’01, ICYFP associate director, are leading research in collaboration with UnidosUS, a Hispanic advocacy organization, to better understand and advocate for the needs of these overlooked children.

Their research has already started to inform policy changes. In December 2020, UnidosUS and other advocates used it to help roll back the exclusion of U.S. citizens in mixed-status families from additional stimulus payments when Congress amended the CARES Act. And in March 2021, UnidosUS’s advocacy helped expand the Child Tax Credit to include these children in the American Rescue Plan. But there’s more work to be done, because the policy rationale for excluding families like Cristian’s from most safety net programs remains in effect.

“How social policy treats children in immigrant families is important to our country, not just to immigrant communities,” says Joshi. “This project is a unique opportunity to get research evidence into the hands of policymakers who are working right now to create a more equitable safety net that includes all children and families.”

Cutting child poverty in half

The 13% child poverty rate in the U.S. is higher than most developed countries, and the U.S. spends less on children than other peer countries do. Between 1990 and 2015, U.S. spending on families never exceeded 1% of GDP. In contrast, spending rose from less than 2% of GDP to nearly 3% in Australia and more than 3% in Ireland and the United Kingdom. Children who grow up in poverty, especially persistent poverty, suffer long-term negative education, health and economic outcomes. And it’s not just an individual cost—child poverty costs the U.S. economy between $800 billion and $1.1 trillion each year, because of increased health care costs, lost adult productivity and higher crime costs.

“The long-term health of our country is shaped by the anti-poverty investments we make today,” explains Acevedo-Garcia. “The research is very clear—the lack of adequate family income compromises children’s development and their ability to achieve success in adulthood. Poverty not only hurts children, it also hurts the economy.”

In recent months, the Biden administration has signed legislation to dramatically reduce child poverty in the short term, starting with the American Rescue Plan. The economic relief package increases the amount of Child Tax Credit per child and expands the credit to include very low-income families. And because part of the credit could be paid monthly, this “child allowance” provides a stable source of income to families whose other sources of income might be erratic and vulnerable to disruptions like work schedule changes or health issues. If these changes become permanent, the U.S. could come close to cutting child poverty in half – a bold but achievable goal laid out in the 2019 National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty.

Acevedo-Garcia was a member of the congressionally-commissioned NASEM Committee on Building an Agenda to Reduce the Number of Children in Poverty by Half in 10 Years that produced the Roadmap. The report detailed policies and programs to achieve that goal, which were incorporated into Biden’s economic relief package as short-term measures.

Congresswoman Rosa DeLauro, a key architect of the Child Tax Credit expansion in the American Rescue Plan, said during a recent public conversation with Dean David Weil, “I am so grateful for Professor Acevedo-Garcia’s leadership in this effort. …It stops being anecdotal when you can stand on the shoulders of that kind of research.”

“The NASEM roadmap showed that we could cut child poverty by 50% if we went down this road,” DeLauro said. “Now, we need to put something in place that is permanent that will allow people to get on their feet, to be economically secure, to take good care of themselves and their families.”

The challenge now is to make sure reductions in child poverty will be distributed equitably across all racial and ethnic groups. If existing exclusions are left unchanged, children in immigrant families, most of whom are Hispanic, will benefit far less than other children.

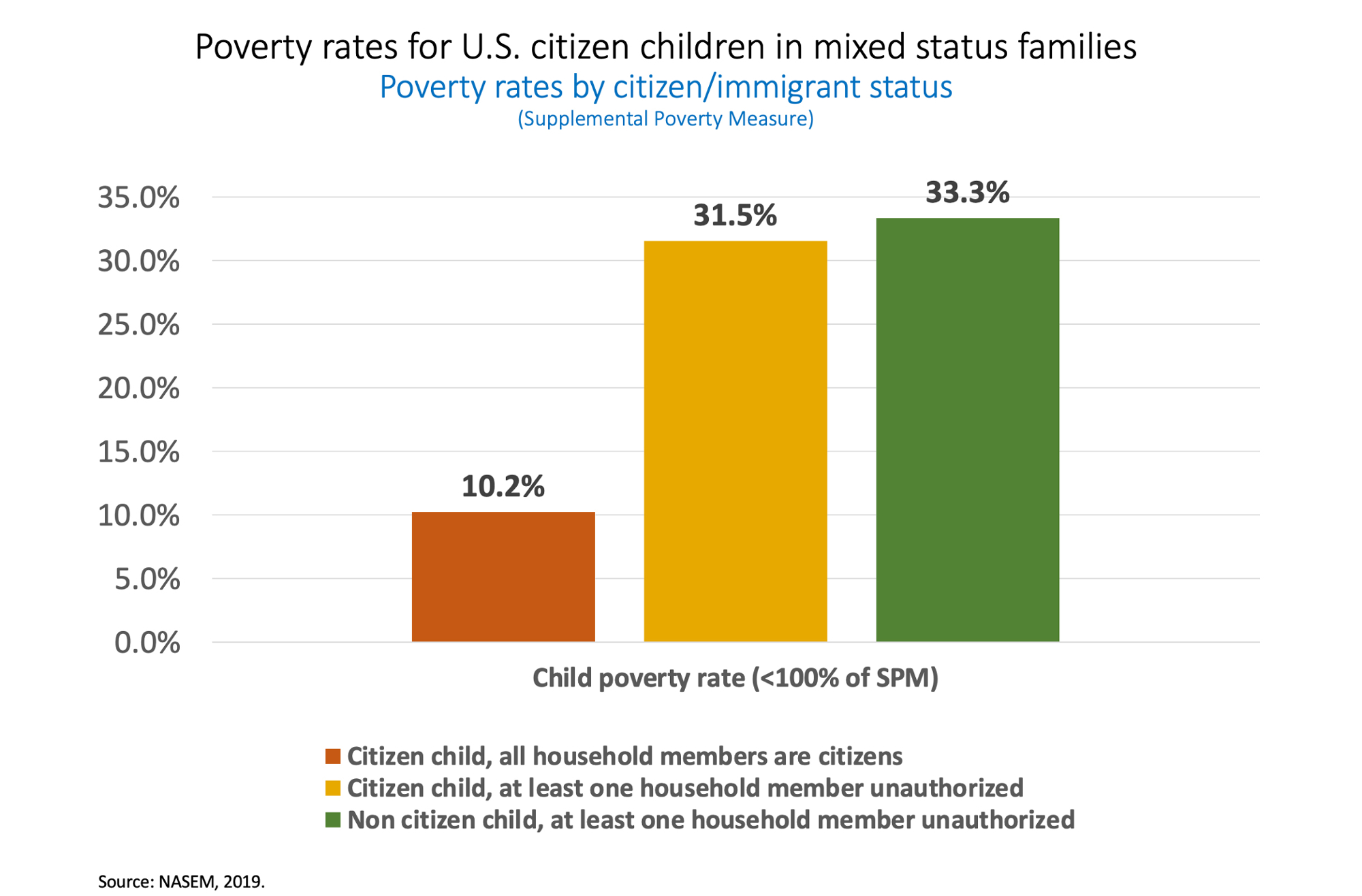

For example, the NASEM report found that a 40% expansion in the Earned Income Tax Credit would reduce poverty by 20% for citizen children in all-citizen households, but it would reduce poverty by less than 3% for U.S. citizen children in mixed-status families like Cristian’s. Mixed-status families, which are disproportionately Hispanic, have different immigration statuses and some have at least one member who doesn’t have a Social Security number.

“Safety net programs are designed to ensure that all children have the minimal conditions they need to thrive,” Acevedo-Garcia explains. “But Cristian and millions of other children who are U.S. citizens are unfairly excluded from these basic protections because their parents are immigrants.”

An unraveling safety net

The exclusion of children in immigrant families from U.S. safety net programs is relatively new. Between 1935 and 1971, no federal law barred non-citizens from Social Security benefits, unemployment insurance, or welfare. The 1970s marked a departure from this inclusive social policy by restricting access for unauthorized immigrants for the first time in U.S. history, leading to a domino effect across programs ranging from Social Security Insurance to food stamps and unemployment insurance.

By 1996, the welfare reform act introduced additional restrictions that excluded legal immigrants such as green card holders for their first five years in the U.S., as well as U.S. citizen children and spouses who live in families with non-citizens.

When COVID-19 hit, millions of immigrant essential workers were excluded from relief measures like the CARES Act payments, emergency food assistance through the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), subsidized housing and Medicaid—right when they needed help the most. Immigrants are disproportionately employed in essential front-line jobs at hospitals, grocery stores, food processing plants and agriculture, and frequently lack access to health insurance, paid leave or personal protective equipment.

“The pandemic presents an opportunity to rethink these exclusions to U.S. social policy, which were driven largely by anti-immigrant and anti-Hispanic sentiment,” says Acevedo-Garcia. “I am encouraged by the new administration’s commitment to reducing longstanding, structural racial and ethnic inequities. Reducing child poverty equitably for children in all racial and ethnic groups requires that we address the structural racism that has produced residential segregation and disinvestment in minority communities and the discriminatory social policies that disproportionately impact Hispanic and Black communities.”

A new Rapid Response Research Award from the W.T. Grant Foundation and the Spencer Foundation, “Including Children of Immigrants in the Post-Pandemic Economic Recovery Efforts and Safety Net,” has allowed Acevedo-Garcia and Joshi to work quickly to produce new research, building on the findings of the NASEM report to provide actionable policy recommendations for the Biden administration. Partnering with UnidosUS, with its decades of legislative experience and deep understanding of how policy is developed and implemented, puts Heller’s research into the hands of lawmakers to develop and implement evidence-based legislation and policy.

Eric Rodriguez, senior vice president at UnidosUS, explains how partnerships between researchers and advocates contribute to more equitable social policy.

“UnidosUS has long carried out extensive policy advocacy on Capitol Hill promoting a more equitable and inclusive social safety net that would end the immigrant eligibility exclusions which harm millions of U.S. citizens in immigrant families,” Rodriguez says. “Partnering with the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy has taken this work to an entirely new level through more painstaking, rigorous research and entree to the country’s most esteemed social science networks. About 5.1 million U.S. citizens were afforded access to previously-denied stimulus payments in recent legislation—a result that would have been much more difficult to achieve without our partnership with the institute.”

Building towards a better future

Back in Florida, Cristian’s dad is working again and the family is slowly paying back the rent they owe. They are thankful that their landlord has been understanding and accepted payments of any size during the difficult months of the pandemic. And although the family has now received some CARES Act payments, which they became eligible for retroactively in December 2020, they are still not eligible for other essential safety net programs like the Earned Income Tax Credit, which could have provided as much as $3,584 based on their income. But because Cristian’s dad doesn’t have a Social Security number, the family will receive $0—even though both parents work and pay taxes.

For the one million non-citizen children living in the United States, the situation is even more dire. They are left out of one of the most important features of the American Rescue Plan, the expansion of the Child Tax Credit, because of a 2018 tax law. The exclusion further adds to the struggles of a population that already has a poverty rate of more than 30%.

Few lawmakers realize the size of the impacted population or the magnitude of these harmful exclusions. But new research evidence from Joshi and Acevedo-Garcia has been crucial in raising awareness among policymakers. This research will continue to inform policy decisions as lawmakers consider making the Child Tax Credit permanent, restoring access to the Child Tax Credit for undocumented children (who were eligible before 2018), and building public support for a more inclusive social safety net.

“The U.S. economy relies on immigrant labor, and as the richest nation in the world, we have a moral obligation to care for all children and ensure that they have the resources they need to grow and thrive,” says Joshi. “But the U.S. is failing many of its most vulnerable children. Building back better requires not just reopening schools and businesses and getting everyone vaccinated, it requires building a more inclusive social policy framework that is explicitly designed to protect all children equitably.”