By Chris Carroll

Last April, as the first wave of the coronavirus pandemic was pounding the United States, some community advocates and politicians began to raise an alarm: The frightening new disease killing thousands each day wasn’t hitting everyone equally. A few months and tens of thousands of deaths later, data from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Medicare and others showed that Black and Hispanic people are about four times more likely to be hospitalized and nearly three times as likely to die from coronavirus as white Americans—a shocking disparity.

Or is it?

For those versed in how racial and socioeconomic factors impact health, the virus’s rampage in communities of color was depressing, but not surprising. Underserved communities face a stacked deck when it comes to COVID risk: a disproportionate rate of chronic health problems linked to poverty and racism; overrepresentation in frontline jobs where infection is more likely; and corresponding underrepresentation at higher organizational levels, particularly in health care. That’s where an earlier recognition of who was getting hit hardest by the virus might have saved lives.

“In the wake of the COVID crisis, there has been intense discussion about the lag time in understanding this disparity,” says Janet Boguslaw, a senior scientist at the Institute for Economic and Racial Equity (IERE) at the Heller School, and an expert in work quality, equity and family financial stability. “That lag happened in large part because (health systems) lack a diverse workforce, which stems directly from a lack of career advancement.”

Boguslaw, the principal investigator, has worked with IERE Scientist Jessica Santos, PhD'15, co-principal investigator, on a long-running research project that’s tackling this lack of representation from both sides of the equation: teaching job seekers and trainees how to better negotiate their planned careers in healthcare, and working to change perspectives and funding frameworks about advancement and equity among those who do training and hiring.

Barriers to Advancement

Over nearly a decade, Boguslaw and her team have partnered with workforce training agencies in New Hampshire and Connecticut that receive funds from the federal Health Professions Opportunities Grants (HPOG) program of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Administration for Children and Families (which also funded the research study). HPOG is meant to funnel low-income trainees from local workforce development agencies into high demand health care positions—certified nursing or dental assistants, pharmacy technicians or medical billing specialists, for instance—that can be stepping stones to well-paying careers. Too frequently, however, it doesn’t turn out that way for workers.

“There is this myth that if people get their foot in the door, there’s a ladder waiting for them to advance,” says Santos, who researches racial and gender equity in labor markets. “But what we have found from these last eight years is that it’s a really long road, and career advancement isn’t nearly as accessible for many people as we’d like to think it is.”

Their own research as well as that of others shows that health care employees who get stranded at the first rung are often low-income women of color. These women receive training and certification through public-funded programs for entry-level jobs that frequently don’t pay enough to support a household, or provide benefits or practical solutions for pursuing advancement. So after a few years as a nursing assistant or home-care attendant, many erstwhile trainees migrate to jobs in retail or elsewhere that have better benefits or pay.

Beyond disappointment and disruption for those aspiring to health care careers, such failures result in worse care for ethnically and racially diverse patients as well.

“If we can make shifts to improve equity in the labor sector in health care, we can improve health care itself,” Santos said. “We know from the research that patients of color have better adherence to treatment, and do better overall, if they have access to providers who are racially, culturally and linguistically congruent.”

Career Roadmaps

To empower job seekers, the researchers developed a curriculum, “Passport to Career Advancement,” which is currently part of the program at the Health CareeRx Academy at the WorkPlace, a workforce development agency in Bridgeport, Connecticut, that receives HPOG funding.

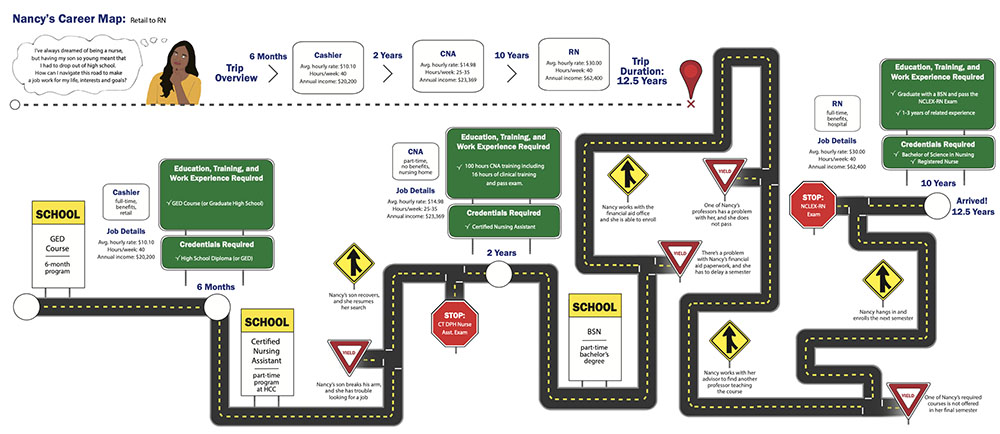

Through the course, prospective employees who enroll at the academy quickly learn that career trajectories are rarely a matter of attending a few months of training and stepping into your dream job. It can instead be a long, winding road—a fact visually presented in the curriculum as virtual roadmaps accompanying stories of real job seekers from the academy.

Each woman starts with different goals and deals with different challenges, which are represented as detours and stop signs on her career map. In all, their career paths from training to target jobs range from 5.5 to 12.5 years—a surprise for some of the participants, who are mostly women of color.

One of the examples highlights the journey of a Bridgeport woman, Nancy, attracted to the field by what she had seen in her own family. “My grandma worked as a nurse and owned her home, so I figured that was probably a great way to make money and secure a good future for my family.”

But unlike in her grandmother’s day, as Nancy learned from a counselor at the Health CareeRx Academy, registered nurses now need bachelor’s degrees. Her first step was to become a certified nursing assistant, a relatively low-paying job that requires only a few months training. Coupled with the demands of working both in retail and health care to make ends meet, and raising a child as a single parent, it took Nancy well over a decade to reach her goal of earning a middle-class income as a registered nurse, as she details in her own words and career map.

“One of the biggest challenges in this work is helping people understand what advancement in health care requires and how to stay on track,” Boguslaw says. “It’s rarely a straight line.”

To help avoid career aspirants being thrown off track permanently, the curriculum builds knowledge of the different options, entry points and potential outcomes. While a two-month training to become a home health worker might seem like a good place to get a quick start, a somewhat longer program leading to an entry-level radiological technician job is more likely to lead to steady employment and benefits.

Beyond providing job trainees with a wide-angle view of the career landscape to help with decision-making, the curriculum focuses on tactics to deal with specific problems, like dealing with family and child care issues or discrimination or other misconduct in the workplace. It teaches the concept of securing “micro advancements”—shorter commutes by transferring to another office, perhaps, or better hours—as steps on the path toward a destination job.

“People came out of the workshops more confident about taking clear actions to advance their career,” says IERE Research Associate Sylvia Stewart, MPP'18, who helped develop the curriculum and present it to job seekers. “They’re able to engage their boss in conversation about a promotion, or they fill out a specific resume for a job they want. They know better how to take the steps they need to take to specific goals, and overall, they felt more positive about their future careers.”

Changing the system

Although the Health CareeRx Academy already took a highly individualized approach to career training, the IERE researchers’ work was still eye-opening, says Nordia Savage, director of the program and vice president of Strategic Initiatives at the WorkPlace.

“I think workforce development in general accepts the idea that you get your foot in the door and you advance, but through this research, we saw that is often not the case,” Savage says.

How does that new perspective play out in reality? Savage gave the example of a young woman she worked with who’d had to drop out just before finishing training elsewhere as a medical assistant (MA)—a job with significant earning and advancement potential. She came to the academy seeking to quickly become a certified nursing assistant in order to save money so she could afford to finish the more in-depth MA program. But armed with knowledge from the Brandeis project, Savage realized it probably wouldn’t work, and instead worked with the woman to help fund the conclusion of her MA training.

“That’s the beautiful thing—this project helped us look at the participants and understand what they didn’t know,” she said. “It broadened our perspective so we can better help broaden their perspective.”

But beyond improved training and placement, more is still needed to build greater diversity in America’s massive health care sector, the researchers say. The conclusion of their HPOG project will be a public policy push this year that will highlight to lawmakers and policymakers the need to fund better job training that sets job seekers of color on the path to higher-quality jobs. Just as important, better salaries for entry-level health care jobs across the board (based on adjusting federal and state reimbursement rates) is essential to ensuring that training leads to jobs that move people out of poverty.

Until then, they say, barriers that create an unbalanced workforce will continue to impede not only the prosperity of communities of color, but as is now playing out tragically during the coronavirus pandemic, their very survival.

“Efforts to reduce health disparities, which are now widely recognized as needing immediate attention, require a direct tie to reducing economic disparities,” Boguslaw says. “Health organizations and policymakers must invest in bringing all populations into the workforce with intention, equity and sufficient funding.”