By Karen Shih

Just a few hours after society collapsed, its members sat in a vast circle, crunching on homemade toffee.

No war broke out—except some verbal accusations about what went wrong. No resources were stolen—except some cookies and chocolate that were redistributed among the members. And there was no foreign invasion—except for the couple of observers who offered their insights.

After all, it was just a simulated society.

But for the first-year students in the MA in Conflict Resolution and Coexistence Program (COEX), who applied everything they learned about negotiation and peacebuilding during their first semester to the exercise, it was an incredibly valuable experience.

“Every time we do SIMSOC (the simulated society exercise), something else comes out of it,” said COEX Program Director Alain Lempereur. “I’ve done this game for 14 years and it’s the first time I had to look up what we do if society collapses.”

In SIMSOC, participants are split into four groups, roughly representing four different economic classes. They must find a way to work together to create a functional—even thriving—society where people are not only fed, but working productively to improve the economy and investing in public welfare and the environment. That’s the only way to keep national indicators at healthy levels, which determine whether the game continues.

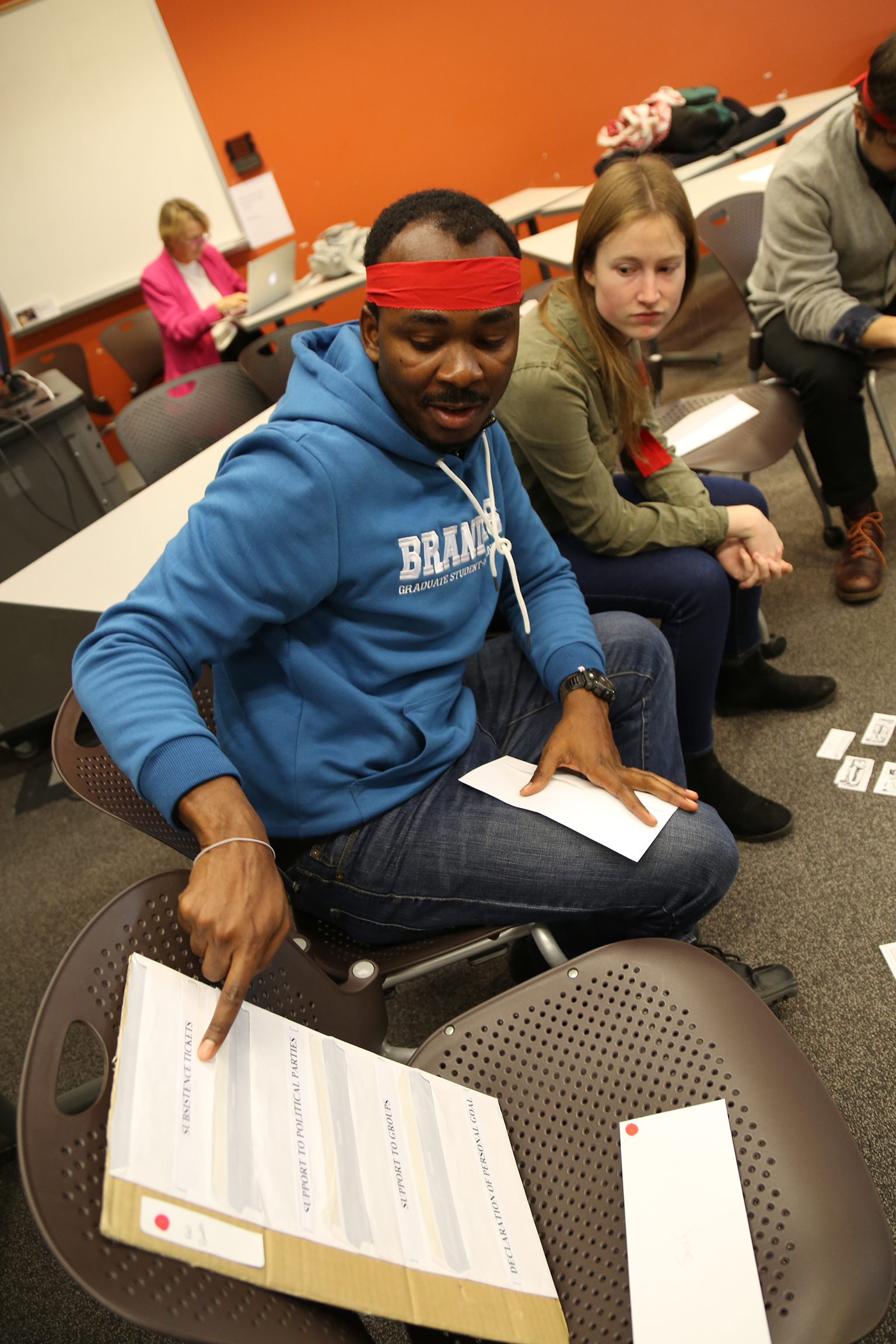

In this year’s simulation, the green team was the richest, with a high concentration of the heads of society’s important institutions like the mining industry, a political party, a non-governmental organization and the judiciary, as well as plentiful food tickets. The blue and yellow were the two middle or working classes, with a couple institutional leaders like the mass media and union heads and some food tickets. The red team had no institutions and no food. Teams were deliberately sequestered in separate rooms for hours as the exercise went on, allowed only to interact with people from other groups if they had a travel pass.

The minimum requirement at the end of each round was for all 45 participants to have a food ticket, which could be obtained directly from someone who had one or through employment. At the end of each round, Lempereur and second-year student organizers Priyanka Renugopalakrishnan, MA COEX’18, and Sarah LaMorey, MA COEX’18, calculated the updated numbers for the national indicators, based on the students’ actions. By round three, the indicators for food and energy supply and standard of living had fallen below zero. That meant societal collapse.

So what went wrong for this year’s COEX class? “You needed to act sooner to get rid of unemployment more drastically,” Lempereur said. “There was no economic activity during the first round whatsoever. There’s no peace without development—you can’t take care of people by just surviving and handing out subsistence tickets.”

But that’s why the exercise is so important—it’s a chance to learn essential lessons without any risk to real people in conflict areas, before the students take their skills into the real world.

The simulation reinforced “the importance of the media to shed light on problems we didn’t know were happening,” said Isaac Cudjoe, MA COEX’18, of the yellow team. With limited travel tickets, most participants relied on communication from the game’s designated head of mass media (who could visit any group at any time) or reports from their own team members to figure out what was happening down the hall.

“I realized how powerful it is to travel to other teams and see what is on the ground in other areas,” said Kate Fahey, MA COEX’19, of the blue team.

Because of the haphazard nature of travel and communication, participants’ intentions were often lost. “Paranoia runs high in this game,” said Lempereur.

The situation became particularly tense between the green and the red teams.

“We came with a human approach to give you jobs and food. You just needed to sign up for our political party and NGO,” said green team member Hauke Ziessler, MA COEX’18, to the red team. “But the moment I entered your room everyone tried the grab the food tickets. Later, when we found out only one person signed up for the NGO, we thought you guys had stabbed us in the back and made a deal with someone else.”

Every group succumbed to regionalism, prioritizing the immediate needs of their members to the long-term prosperity of the society.

“SIMSOC showed us how hard it is to change systems,” said Marine Ragueneau, MA COEX’18, of the red team. “We were idealistic but still reactionary when we had the chance to create our own society. It’s discouraging but invigorating.”

After nearly two hours of discussion, as the emotionally exhausted students laughed and shared their frustrations, pointed the occasional finger and offered thoughtful self-reflections, Lempereur wrapped up the day.

“Can you reconcile self-interest with the interest of everyone? When we are in positions of wealth and power, we behave exactly as expected. When we have basic needs we need to fulfill, that’s the priority,” he said, touching on the power dynamics that ruled the day. “I hope you understand why I love SIMSOC. It’s a way to pull it all together.”