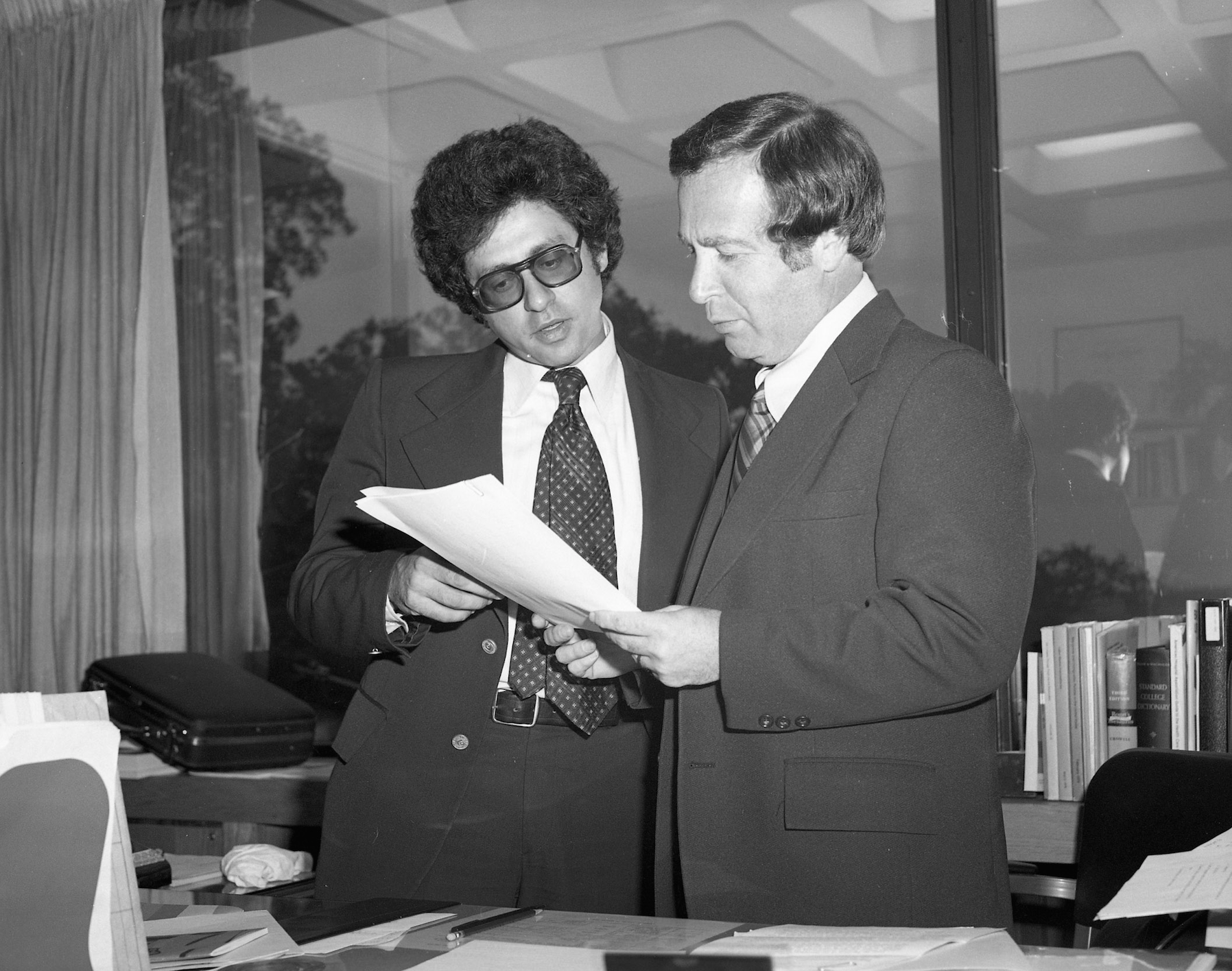

When he came to the Heller School in 1978, economist Stan Wallack had already played important roles on the national policy stage, having served as an economic policy fellow at the Brookings Institution and as a policy analyst with federal agencies including the Department of Health, Education and Welfare and the Congressional Budget Office.

“While in Washington, Stan was a driving force to reform our healthcare system,” recalls Stuart Altman, who recruited Wallack to become the founding director of Heller’s new institute for health policy. “Stan was an important reason why Irving Schneider chose to provide endowment support for this new institute, which now carries his name,” Altman says. “It’s hard to imagine that we’d have the Schneider Institutes today without him.”

During the next four decades, Wallack led the Schneider Institutes as it became what Heller Interim Dean Marty Krauss calls “one of the great health policy centers in the country.”

In his own work, Wallack analyzed problems in the financing and delivery of health services, in hopes of finding innovative solutions. One of his first major accomplishments at Heller happened in the early 1980’s, when he examined the uncontrolled, high-costs associated with long-term medical care—a problem that particularly impacted America’s elderly population. Wallack developed the concept of the Social Health Maintenance Organization, or SHMO, which served as a precursor to the current Medicare Advantage Plans.

Twenty years later, another of his research projects helped restructure how the federal government paid health care providers by linking incentives to achieving both financial savings and improved clinical outcomes. The project inspired the idea of Accountable Care Organizations.

Over the years, Wallack’s research interests diversified. “He became passionately interested in aging, mental health care, global health and organization and management,” Altman says. “Stan’s intellect was eclectic and as a result, the Schneider Institutes had a broad-based focus on a wide range of issues.”

Constance Horgan, the director of Schneider’s Institute for Behavioral Health, says while many people will remember Wallack “for his creative thinking about the design of the healthcare delivery system in our nation, and about his brilliant leaps of intuition about what the next important policy issue might be,” she prefers to focus “on the quiet moments, the ones that happened day in and day out—his sage advice about leading an institute, his interest in making everyone's work life better and his ongoing interest in the details of being a mentor and a colleague.”

In addition to his leadership at the Schneider Institutes, Wallack also played a pivotal role on the academic side of Heller. “He was very much involved in ensuring the highest standards for his students,” says Altman. “Many have gone on to earn PhDs and become senior policy advisors in Massachusetts and around the country.”

Some of his former students, like Michael Doonan, who now directs Heller’s Master of Public Policy program, ultimately became Wallack’s colleagues. “While incredibly accomplished in helping shape national health policy, Stan always took the time to mentor, prepare, and inspire the next generation of health services researchers,” Doonan says. “He brought the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) Training Program to Heller, provided research opportunities and mentorship and was always generous with his time and access to his expanded network. In addition to his direct contributions, his impact will live on through his students.“

Another of his former students, Schneider Institutes researcher Cindy Thomas, says Wallack “drove us to be better thinkers, and created an environment in which new ideas flourished. I know no one who was better at challenging our intellect, while remaining focused on solutions to real world problems.”

Interim Dean Krauss says Wallack embodied Heller’s institutional spirit as a mission-driven school. “He inspired those he recruited to investigate common assumptions about health care in all its dimensions, to dissect those assumptions in a systematic way and then to propose innovative alternatives,” she says. “He is the architect, with his colleagues, of many of the most innovative advances in how health care can be organized, structured, and financed to better meet the comprehensive medical and mental health needs of all Americans. He was always ahead of the curve."

Allyala Nandakumar, who Wallack hired as director of Schneider’s Institute for Global Health and Development, similarly describes him as “a visionary who used his superb intellect, incredible confidence and sheer force of personality to transform and reshape the health care system in the U.S.” But what mattered more, Nandakumar says, was how deeply Wallack cared for those who worked with him. “He gave so much of himself expecting so little in return. He was the eternal optimist, always excited about what lay around the next bend in the road. I walked over to his office this morning and peeped in through the door. It was as he had left it on Tuesday: papers strewn around; a sweater hanging; photos of his family; a coffee cup and a bookshelf full of interesting readings. The only thing missing was Stan. There never can or will be another human being like him. He will be missed more than we can even begin to fathom."