By Danna Lorch

More than 4.5% of African Americans grapple with alcohol use disorder, an addiction that tears apart their lives and sense of self-worth. Yet their recovery trajectories have rarely been researched in depth, and the few studies that do exist compare small samples of Black people to larger samples of white people, and provide little insight into the experiences of African Americans involved with substance use and recovery.

Senior research associate and lecturer Robert Dunigan, PhD’04, has built his academic career on changing that dynamic by developing strong relationships with institutions and organizations serving primarily people of color. Previously, Dunigan was a social worker who supported adults profoundly affected by mental illness and addiction. “I was serving a very diverse population and fell in love with them and the work,” he says.

Dunigan initially entered the MSW program at Boston College, aspiring to have a leadership role in his job but unexpectedly discovering a propensity and a passion for research, which led him to the Heller PhD program. He is currently a co-investigator on Understanding Pathways to Wellness and Alcohol Recovery in Detroit, known as the UPWARD study.

Funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, UPWARD is a partnership between Heller’s Institute for Behavioral Health and the Detroit Recovery Project, a nonprofit providing Black-majority populations with outpatient recovery-support services for substance use and co-occurring mental health disorders.

The study aims to define what recovery means to Black communities, how it can be measured, and how to advance recovery journeys. From the very beginning, the Detroit Recovery Project staff were included as UPWARD co-investigators, and the populations they serve were briefed on the project through a community advisory board and regular briefings.

Many previous studies on polysubstance use and recovery reduce those struggling with substance use down to their addictions rather than taking a whole-person perspective. The initial phase of the UPWARD study involved 37 in-depth interviews that took a qualitative-first approach.

Dunigan explains, “We interviewed an all-African American population, asking individuals about not only their backgrounds but also what engaged them and retained them in recovery. In other words, which methods and factors work.”

While Dunigan and his colleagues went into the study with the assumption that they would hear about more polysubstance use with drugs rather than alcohol, the interviews revealed otherwise: The majority of their participants’ entry substance was alcohol.

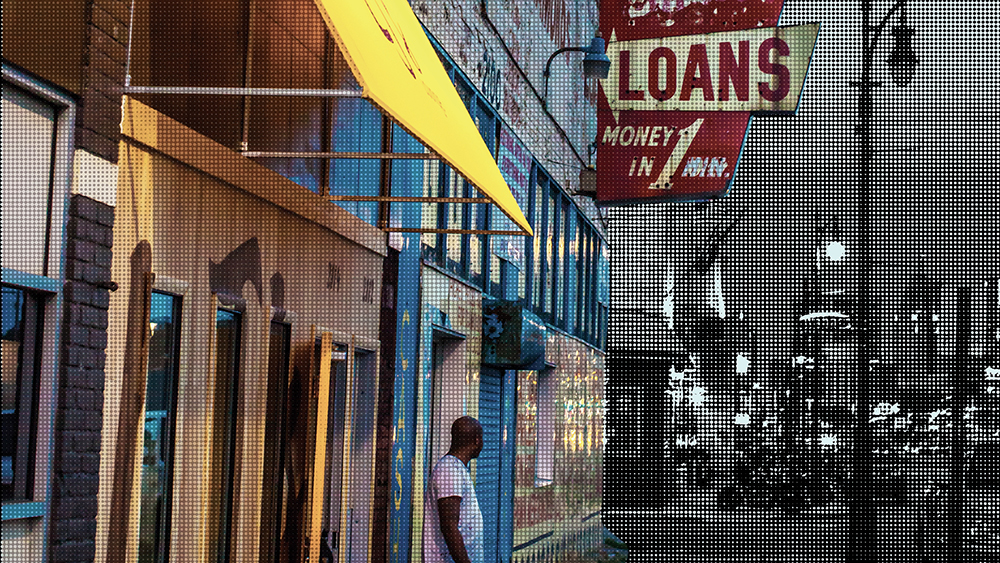

“I was surprised by how many folks talked about beginning alcohol use at an early age,” Dunigan says. “It had a lot to do with availability. The corner liquor store. Access to alcohol within the home. A lot had to do with dealing with issues around poverty, trauma, and colorism.”

For example, one young woman described how when she was in middle school, she was looked down on by her peers for the color of her skin and her figure. “She didn’t have the phenotype associated with attractiveness. She used alcohol to numb the pain beginning in junior high school,” Dunigan notes.

He and his Heller colleagues, including principal investigator Sharon Reif, PhD’02, with whom he’s collaborated since their graduate school days, as well as a team of research associates, presented their findings at three conferences in 2024. They shared their initial results on a poster at the National Conference on Addiction Recovery Science.

Launching in fall 2024, phase two of the UPWARD study will analyze the interviews to identify different groups based on their pathways through recovery, letting the qualitative analysis guide the quantitative, reviewing respondents’ experiences, and looking for emerging trends and patterns in long-term outcomes.