By Tony Moore

“Let’s grab a drink after work.”

“It’s 5 o’clock somewhere.”

“Another round?”

Most people reading this article have likely heard at least one of these phrases before. Alcohol is consumed in many cultures across the globe in different ways, in different settings, for different reasons. It is used socially around sports, concerts, and weddings.

In the United States, in fact, according to the 2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, 86% of adults reported that they drank alcohol at some point in their lifetime.

Also in 2019, 26% of adults reported that they binge drank in the previous month, which rounds out to a woman consuming four or more drinks or a man consuming five or more drinks in about two hours.

And you’re probably thinking — that’s not very surprising.

Maybe none of these findings will be either: According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, around 95,000 people die from alcohol-related causes annually, making it the third-leading preventable cause of death in the U.S. Alcohol contributes to about 18.5% of emergency department visits, and a decade ago, alcohol misuse cost the U.S. $249 billion per year. The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) website detailing the detrimental effects of alcohol misuse on people, families, society, and U.S. and global health care is exhaustive (and exhausting). The site also includes The Healthcare Professional’s Core Resource on Alcohol, which provides guidance on evidence-based care for patients who drink alcohol.

All of this evidence is why the Heller School’s Institute for Behavioral Health (IBH) of the Schneider Institutes for Health Policy and Research launched its NIAAA training program in 1994, preparing doctoral students for research careers in universities, governmental agencies, and other settings devoted to alcohol-related services research. The strength of the program has been the quality and breadth of its faculty and researchers and its home in IBH, with its active research portfolio that provides opportunities for trainees to serve as graduate research assistants, participating as part of the research team and contributing to analyses, presentations, and publications.

Training the next generation

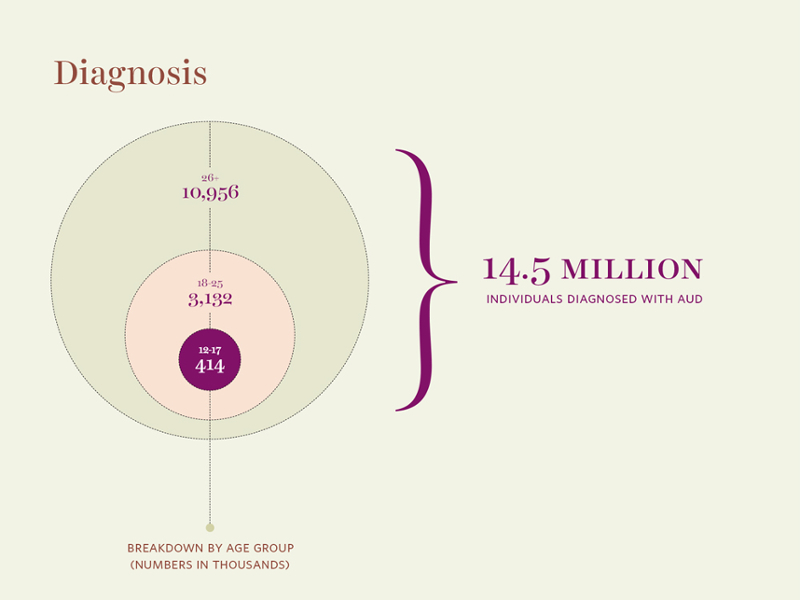

According to Constance Horgan, professor and director of IBH and co-director of the Schneider Institutes for Health Policy and Research, “Alcohol is the most commonly used substance in the United States, with approximately 69.5% of adults consuming alcohol in a given year, and about 15 million persons age 12 and over estimated to need treatment for alcohol-use disorder.” She also notes that around 65 million people in the U.S. engage in risky alcohol use, while only 10% of those with substance-use problems seek help.

“Alcohol-related services research is vital to changing this situation through improved systems for prevention, treatment, and recovery services,” Horgan says. “Training the next generation of alcohol-services researchers is crucial because of the continued magnitude of alcohol problems in the U.S., the complexity of delivery systems, and the rapid changes in the overall health environment.”

Funded by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, Heller’s NIAAA Training Program in Alcohol-Related Health Services Research was recently renewed for another five years. Led by inaugural director Horgan since 1994, the program remains a full-time PhD fellowship that includes full tuition support for three years and an annual stipend, with a fourth year of funding available through the Heller School. And it continues to lead its graduates to successful careers in the field.

“I think it would be fair to say I wouldn’t have been aware of this opportunity or qualified for it without the mentorship, training, and exposure to national behavioral health policy I received in the NIAAA program at Heller,” says Timothy Creedon, PhD’14, of his current position as a behavioral health services researcher and policy analyst with the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation.

He explains, “The program provided the quantitative research methods expertise I need for this job, as well as the subject-matter expertise required with respect to alcohol-use disorder treatment policy — and policy regarding other substance-use disorders and mental illness.”

Where alcohol and society meet

The program focuses on studying the many facets and inherent intersectionality of alcohol prevention and treatment services, from organization, financing, and management to the quality, cost, access to, and outcomes of care. Graduates go on to research careers in universities, governmental agencies, or other research settings devoted to alcohol-related services research.

“The multidisciplinary approach of the program is critical because alcohol-use issues in the U.S. are complex and multifaceted,” says Creedon. “The NIAAA program trains new researchers to build a full-spectrum view of the numerous, multilevel challenges that need to be addressed in order to implement effective policies for preventing and treating alcohol-use disorders and their consequences with accessible, quality interventions.”

Sharon Reif, PhD’02, a professor and division director in IBH who also was trained in the NIAAA program, emphasizes the importance of conducting research across the full breadth of alcohol prevention, treatment, and recovery services, learning what works and for what populations while stressing that research on its own isn’t enough to address society’s needs — needs that often exist outside a clinical setting at the far side of the “research to practice” continuum.

“We must understand how to address alcohol problems in the real world, within systems of care that intersect — for example, health, social services, criminal-legal — and with an understanding of the workforce, payment/financing, and policy issues that determine how services are implemented,” Reif says, emphasizing that certain treatment approaches may not be available in the “real world” because of existing insurance or policy issues. She also says that learning where the application of research falls short is not only eye-opening but instructive, allowing health services researchers a chance to identify how these practices could be expanded and sustained across systems and populations.

Trainees learn to examine these types of questions: How do people get access to alcohol-related prevention and treatment services and determine if they are of high quality? How much do these services cost? What is the outcome as a result of this care? Trainees study the most effective ways to organize, manage, and finance high-quality care based on evidence, and they gain the research skills to address the financing, delivery, policy, workforce, and other mechanisms to more fully support people with alcohol problems.

Boots on the ground

Before enrolling at Heller, Brooke Evans, PhD’17, was a clinician and supervisor in behavioral health settings. Now, she’s a senior research associate at Comagine Health, where she leads research and evaluation projects centered on implementing, improving, and evaluating behavioral health services — particularly substance-use prevention, treatment, and recovery programs. Evans says the NIAAA program can prepare students to succeed “in just about any advanced career in research and policy you might hope to pursue,” a point her trajectory proves well.

“My career path has been shaped by the research skills, mentorship, and other opportunities that I received through the NIAAA program at the Heller School,” Evans says, adding that the program provides all of the financial support, research opportunities, and expertise that scholars interested in advancing the knowledge base in alcohol and other substance use and misuse require. “The NIAAA program provided me with the chance to deepen my knowledge surrounding alcohol and other substance use and integrate my clinical background and understanding. It also offered new knowledge as well as research skills and methods to inform and effect policy and system-level change/transformation.”

To prepare for a life in the field, students in the program participate in ongoing projects with experienced researchers who are engaged in a wide variety of studies that address alcohol-related services and policy concerns, working either at Brandeis or at a research setting outside the university.

In the classroom, the NIAAA program offers its doctoral students a core curriculum that stresses conceptual models and research methods and competencies, emphasizing the societal context for alcohol treatment and prevention services and the intersection of these services with behavioral health, general health care delivery, and other service systems.

Serving at-risk populations

Also residing at that intersection are issues of how alcohol use and abuse affect certain populations that are more at-risk than others.

“Many people with addiction problems have other experiences that can also contribute to their vulnerability, and social determinants of health — such as insufficient housing, income, food supports, insurance, social supports — that may create conditions for which alcohol use is a coping mechanism or that interfere with the ability to seek help for alcohol problems,” says Horgan.

She adds that many people with alcohol or drug problems also have mental illness or psychological distress which, in turn, increases vulnerability. “Experience of trauma is quite common among people with alcohol, drug, or mental health problems. Each of these types of co-occurring disorders or experiences contributes to increased likelihood of unhealthy alcohol use and reduced likelihood of seeking treatment or having access to care.”

Reif says the program brings an enhanced focus on race, ethnicity, and gender. “These groups may differ in rates of alcohol use and problems but generally have had less access to treatment,” she continues. “In part, this reflects interventions that were not developed specifically for these groups, but it may also reflect systemic inequities in systems to address and pay for substance use problems.”

For Andrea Acevedo, PhD’08, associate professor in the Department of Community Health at Tufts University, these issues are at the forefront of her work as her research focuses on racial/ethnic equity issues in substance use and substance-use treatment services.

“I use a multilevel approach to understand the multiple factors — for example, individual, facility, community, and policy factors — that might contribute to inequities in services and outcomes, and factors and policies that might help reduce them,” says Acevedo, who spends her time both in and out of the classroom conducting research and teaching courses on substance use, policy, and quantitative methods, all at the heart of the NIAAA program.

“As a fellow in the program, I had the opportunity to learn from and work with some of the top addiction health services researchers in the country, right at Heller,” she continues. “I received excellent mentorship and had opportunities to publish, attend, and present at conferences and meet other top addiction researchers who were invited to speak at IBH or through the conferences. If you are interested in addressing alcohol- or substance-use problems through research, as a fellow in the NIAAA training program at Heller, you will receive unparalleled research training.”

What’s abundantly clear is that the training leads to fulfilling careers that not only allow graduates to make valuable use of their degrees, their time, and their energy for the field but also to make a difference.

“One of the things that keeps us going is seeing the contributions that so many of the individuals we have trained are making in improving both the broader societal consequences of alcohol problems, as well as the lives of persons with addiction issues,” says Horgan. “That is an immensely rewarding goal.”