By Rachel Horvath

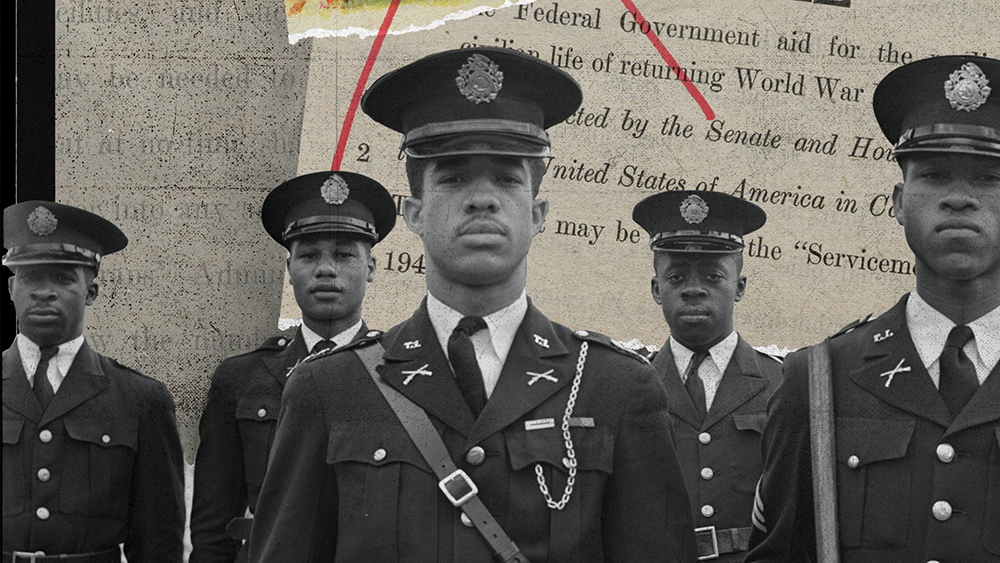

When millions of U.S. servicemen and servicewomen returned home at the end of World War II, the 1944 Servicemen’s Readjustment Act, more widely known as the GI Bill, offered a broad range of benefits for reentry to those who served their country. But a study done by Heller’s Institute for Economic and Racial Equity (IERE) reveals the struggle that Black veterans faced as they tried to obtain their GI Bill benefits, leading to generations of inequity.

The way the GI Bill was written, its goal was to distribute benefits in education, homeownership, and unemployment fairly and equally for all veterans. However, the localized implementation challenged access to these benefits for Black service members, leaving ample room for discrimination. At the same time, white service members and their families flourished in post-war society.

Understanding Black Voices

A key part of the IERE research involved talking to both Black and white World War II veterans and their families. White interviewees spoke about the opportunities that the GI Bill provided for economic mobility. Education helped veterans pursue more well-paying jobs so they could provide better lives for their families, and home loan guarantees allowed white homeownership to skyrocket.

But Black interviewees painted a different picture. They talked about the discrimination they saw while serving and upon returning home, and the difficulties they faced when trying to obtain health care and other benefits from their local Veterans Affairs offices. Service members, both Black and white, put their lives on the line for their country during the war, but unlike white veterans, Black veterans faced open hostility from the society they had helped to preserve.

Inequity in the Implementation of the GI Bill

The research took a close look at available data from annual VA reports and veterans surveys collected between 1950 and 1987. According to the data analysis, the U.S. government allocated a similar amount of funds per person for GI benefits to both Black and white veterans. Nevertheless, there was a contrasting distribution pattern of benefits overall, with Black veterans receiving fewer home loan guarantees. This means that Black veterans were staying in impoverished areas instead of moving to the suburbs, as their white counterparts did.

It was also found that though Black veterans received more heavily subsidized educational opportunities, many of these opportunities were of low quality. Instead of enrolling in high school, college, or graduate programs, as their white peers did, many Black veterans registered for vocational training programs, which offered a lower return when it came to lifetime earnings.

A Lasting Impact

Many descendants of white World War II veterans can still feel the value that the GI Bill provided their family members. White service members were able to obtain funding for the education and housing needed to build a solid middle-class foundation. Generational wealth was built upon that, with their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren feeling the repercussions of stable, secure housing, college education, and more, decades later.

Black veterans, however, didn’t have the opportunity to build this foundation for generational wealth, especially in terms of homeownership, and, as decades passed, the financial gap widened. The research done at IERE notes that while the descendants of Black veterans do hold more wealth than those of Black non-veterans, the wealth gap between the families of white veterans and the families of Black veterans is staggering. The researchers found that the families of white veterans held, on average, 32 times the wealth that Black veterans did.

With the 80th anniversary of the GI Bill quickly approaching, the repercussions of this legislation can still be felt today. Though the benefits of the bill were open to all veterans, Jim Crow-era discrimination prevented Black veterans from receiving the same opportunities as their white counterparts. The years and generations have widened this wealth gap and magnified the struggles that many Black Americans face today.