By Bethany Romano, MBA’17

Illustration by John Jay Cabuay

In September 2021, University Professor Anita Hill released her third book, “Believing: Our Thirty-Year Journey to End Gender Violence,” a comprehensive examination of gender-based violence. In it, she provides a breathtakingly thorough and occasionally gut-wrenching review of the myriad ways that this violence infiltrates and damages lives, communities and social structures.

Hill connects the dots from elementary-school bullying to college sexual assault, workplace harassment and intimate partner violence, laying bare the broken systems that often fail to provide accountability or properly investigate complaints. Along the way, she interweaves stories from her own life and others’, poignant reminders that although gender-based violence is almost too ubiquitous to fully comprehend, its consequences are meted out on individual lives.

Hill spoke with Heller Communications about the book, the true scope and impact of gender-based violence, and her goals and ambitions for change. These are edited excerpts from that conversation.

You describe “the struggle” for social change as neither a race nor a marathon, but a relay. How does “Believing” contribute to that relay?

Gender-based violence has been passed from generation to generation. If you consider all the different behaviors that fall under that category, it includes bullying, harassment, sexual harassment, sexual assault, rape and intimate partner violence. It’s an intergenerational problem that implicates all of our systems.

This is not going to be solved in one generation, and that’s what I mean by the relay. I feel like this book sheds light on the whole of the problem and the connection between the different behaviors that drive it, how it’s built into our structures and systems. That means some things won’t be done in this generation. But it also means that we have to get started.

I talk about this as our country’s 30-year journey, but it’s really just a slice of the longer journey. Many people have gone before me. Many people are traveling with me. And I hope there will be many to follow.

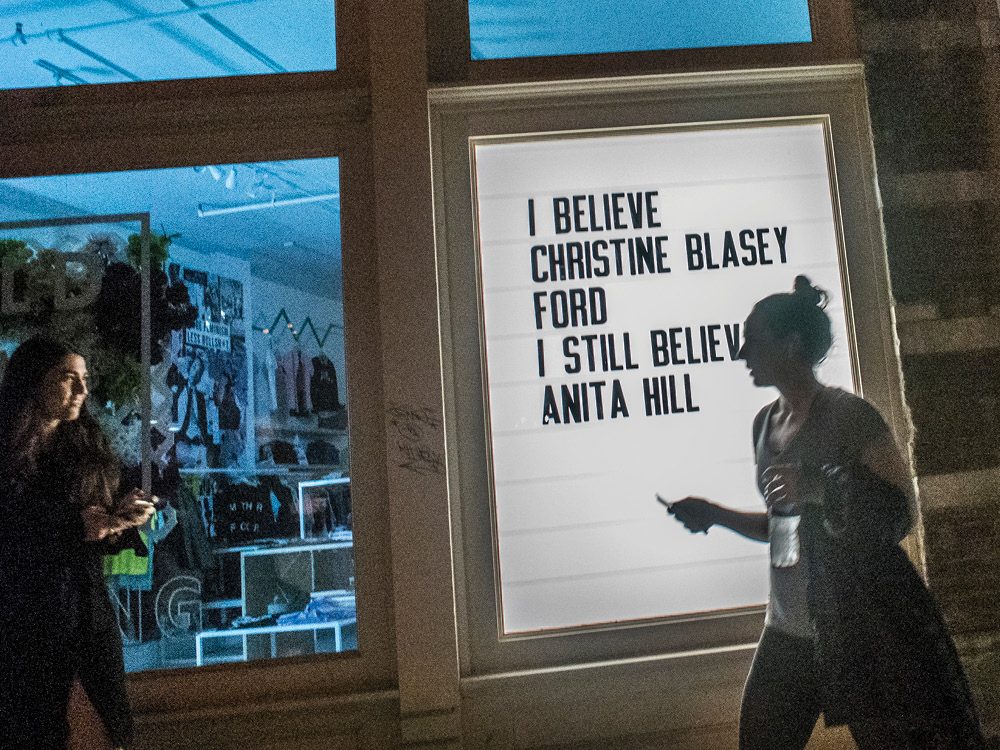

There’s a section of the book in which you bounce back and forth between your 1991 testimony and Christine Blasey Ford’s in 2018. It illustrates how aspects of our culture have changed in the last 30 years, but the rules of those Senate proceedings did not. What are some of the gaps in those proceedings, and the legal system more broadly, that you wish more people were aware of?

In 1991, as well as in 2018, there was no transparency or clarity on how to file a complaint, what the contents of a complaint should be, who would investigate it, how thoroughly it would be investigated — I mean, there was no process. What happened in Washington seems really odd and sort of spectacular in terms of a failure, but it’s a replica of what is happening in many, many settings.

Some of the details may be different, but the overall lack of transparency and clarity, and the intention for the system to help survivors and victims, are not there. Where does a person who is working in a factory, or in Silicon Valley, file a complaint? What can they expect to happen? Will they ever know whether it’s been investigated? And if they are a gig worker, contract worker or volunteer, there may be no recourse at all.

When we think about the legal processes in a sexual harassment case, ultimately it comes down to whether a judge or jury determines that the behavior was “severe or pervasive.” And that term is very broadly interpreted. In some cases, really egregious, derogatory remarks about women have been categorized by judges as “stray remarks,” which the law does not protect against. And it’s not just verbal comments; often, even physical touching is tolerated under the “severe or pervasive” standard.

And, of course, there are problems with the criminal justice system. The actual number of rape cases that are brought to trial is minuscule. According to a Washington Post article, less than 6% of rape complaints result in arrest, and only 1% are referred to a prosecutor. A massive number of rape kits are shelved and completely untested, or await DNA analysis. The system allows police officers broad discretion in investigating claims, and they sometimes misclassify or dismiss claims of rape because they don’t believe prosecutors will pursue them. It also allows prosecutors to determine whether they’ll pursue a claim, and they want to make sure it’s a winner.

And on top of the systemic failures and structural failures, there are cultural issues, including victim blaming. You have to put all the dots together to understand the colossal problem we face. This is why, I believe, we do not have stronger protections and why our rates of abuse are so high.

So, given how massive and multisystemic the problem is, how did you decide the boundaries of this book?

I’m smiling now because someone said to me, “You know, you’re trying to take all this on; it’s like boiling the ocean.” And it is. There’s this ocean of behavior out there. We know it’s happening to our neighbors, our friends, our co-workers. In some ways, I think people feel that this problem is so big, we can’t fix it. What I decided when I started out is to develop the mindset that it’s so big, we have to solve it.

Too many lives are at stake, too many individuals’ well-being is at stake. When you talk about this problem in terms of our military, our national security is at stake. Our confidence in our courts is at stake. All of those things are at stake, and that means we need to do something.

I decided to think about it in terms of people’s lives. I write about what happens to children in elementary school who are bullied because of their gender, gender expression or sexual identity. Then I take it through college, and ultimately into the workplace, homes and the larger world of politics. I look at how race, ethnicity, sexuality or sexual identity impact the experiences of victims and survivors. I wanted to break it down in terms of how people experience this behavior throughout their life. I wanted to humanize it.

One of the most important parts of the book to me is the chapter on race- and gender-based violence. I talk about the role of race and some of the dilemmas that women of color face coming forward into systems that continue to be racist. Anti-racism is not going to eliminate gender-based violence, but you can’t eliminate gender violence for women of color unless you take on racism. That chapter also includes sections about the sexual assault of boys, and about male gender policing that usually shows up in the form of violence. I put all of that together in one chapter because shaming is at the core of many of those experiences.

I also wanted to answer some questions I have been asked along the way, like: “What do I tell my daughter?” My answer is, talk to your daughter, but also talk to your son. There are two reasons: First, we know men are more likely to be perpetrators, or if they’re not perpetrators, they probably know others who have participated in this kind of behavior. And the other reason is because one in six boys and men has been a victim of sexual assault or some kind of violation. That is a lot. We can’t forget about that.

You need to talk to both, but you can’t let the conversation stop there. You’ve got to talk to teachers, principals, superintendents, the school board or whoever is shaping the experience of students in school. And you’ve got to demand accountability.

You take a lot of care to explore how gender-based violence does great harm to families and communities, in addition to individual victims and survivors. Could you talk a little bit about that?

We never want to make the survivor secondary, and that is not my goal, but I think most survivors would tell you that the harm is not to them alone. There’s harm to their family, to their relationships.

If we look at intimate partner violence as just one example of behavior that harms us all, an estimated 10 million people per year in the U.S. will experience some kind of domestic or family violence. Many of those people — one estimate is 38% — will become homeless as a result. We know that when people are homeless, there is an impact on the education of their children. They may have problems keeping a job, or more absences from work. Part of the cost is lost productivity. There are also medical costs, and societal costs, to support individuals who experience intimate partner violence.

There’s an emotional impact on the community as well. In the book, I talk about a community where there were five murder-suicides within the span of two or three years. Just think about all of the people who suffer. One woman worked as a cashier at the grocery store. One drove a school bus. One was very involved in Little League. One person, who knew one of the victims, said, “He didn’t take her from one person, he took her from all of us,” meaning all of the people that she knew in this community.

The children of these individuals suffer. Co-workers are impacted, families are impacted, people you do volunteer work with or people you worship with. Communities are left wondering: What could we have done to prevent this?

In your introduction, you say, “I envisioned myself as an educator, not a crusader … I do not fit the stereotype of a movement leader.” How do you think of yourself as a change-maker?

I want to make people aware of the problem, offer a solution and make them believe that solutions are possible. I don’t know exactly what to call that. I tell people that I’m not an activist because an activist has to be a really good organizer. There are things that I do pretty well, which is research and putting together information. But organizing people? No.

I decided that I’m not going to try to deal with just one piece of this problem. I’m going to deal with the whole of it. I know what I want to do with my work, and I want to use every tool we have.

We need to be out there measuring more. In 2018, Sens. Warren, Gillibrand, Feinstein and Murray sent a letter to the Government Accountability Office asking them to calculate the economic cost of sexual harassment in the workplace. And the answer is, we don’t really know. We know there are health implications and housing implications, workplace and productivity implications. But our government has not calculated the overall cost of those impacts.

As the saying goes, you can’t fix what you haven’t measured. But to go along with that, what we care about, we do measure.

At the end of your book, you call on people at the highest levels of power — including President Biden — to take action.

I talk about Joe Biden and the role that he can play, and I call for policy change that could begin to acknowledge the problem and commit resources, with an array of our federal agencies solving it. But I’m really talking about all leaders of all institutions. Whether it’s the CEO of a company, or the president of the United States, or admirals and generals in the military. Leadership needs to address this as a public crisis. We need to really closely examine our structures and understand how they actually support this problem instead of solving it.

I do want people to have hope, because I think we’ve come so far. We know more because researchers are amassing the knowledge to inform better approaches. All the research and all the work that people are doing has revealed and educated people about gender-based violence. Public sentiment has changed, and people expect and are willing to demand accountability. Survivors and victims have found their voices. All this gives me hope. And even though Christine Blasey Ford’s outcome was similar to mine, the public response was different. As a culture, we’ve moved. Now it’s time to take the knowledge and energy and go forward to demand change.