By Karen Shih

Photos by Kevin Brown, Johnny Khan, and Tasnim Zaki

The remote mountain region of Gilgit-Baltistan in northern Pakistan — where K2 and several of the world’s highest peaks tower above turquoise glacial lakes and rivers — holds special meaning for Ambreen Khan, MA SID’19.

Most of her childhood summers, her father and uncle would pack up their combined 13 kids in the crowded city of Karachi, the largest in the country, and head north to their ancestral village in the Hunza Valley. There, Khan and her siblings played in the fields and fresh mountain air with their cousins. Khan, always a leader, often rallied the other kids for games and adventures.

“As pretty as the valley was, I always thought, ‘I’m here for summer break and I can leave, but what about my cousins and other family members, especially the young girls?’ There’s no infrastructure, no roads, no bathrooms here,” she says. Beyond marrying young and having a family, Khan saw few opportunities for girls.

Years later, after Khan established herself as a successful couture fashion designer and television host, these childhood experiences motivated her to use her skills and influence to establish the Empyrean Foundation, a nonprofit organization that teaches income-building skills to women and girls. In the years since, she’s adopted a nimble, hands-on approach that has taken her work from artisans and garment workers in rural and urban Pakistan to Afghan refugees in her new home of Dallas-Forth Worth, Texas.

An unexpected path

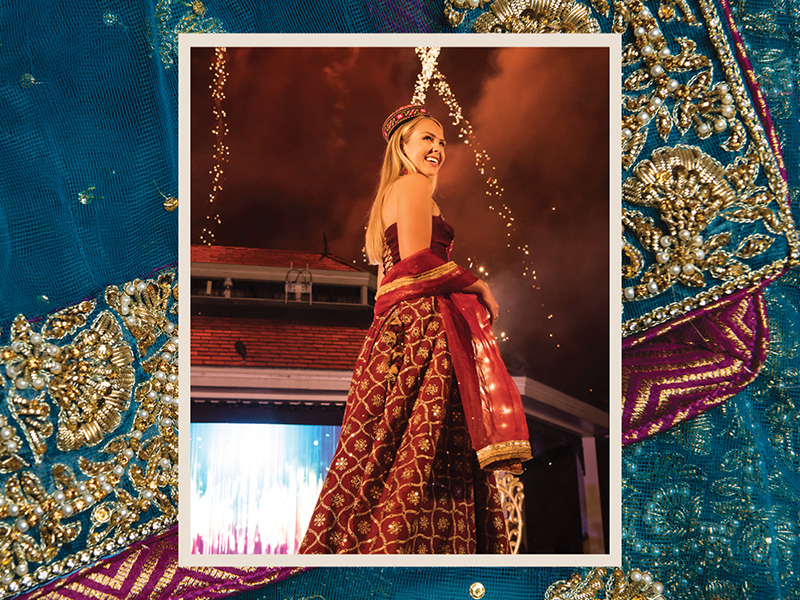

It’s easy to get lost in the beauty of Khan’s bridal designs. The intricate embroidery, detailed ornamentation and geometric shapes, which echo the Mughal architecture that inspires her, create complex patterns across the flowing fabric.

That complexity is reflected in Khan’s life, which never followed the path others may have expected from her.

“The elders established in my head that I would be a doctor or a nurse, or go into computer science or become an accountant,” she says. “But none of that was for me. I was so into art and fashion, but no schools in Karachi taught fashion design.”

Not to be discouraged, she started making clothes at home. Her mother taught her to make harem pants. From there, Khan kept experimenting.

“When I was 15, I designed a tunic with embroidery and flared pants for me and my friend — we became very famous at school,” she says. “My dream was to go to the U.S. and study at FIT [the Fashion Institute of Technology in New York City],” but her family didn’t have the means to send her abroad.

Instead, she studied commerce as an undergraduate. But just as she finished her degree, Karachi became home to the Asian Institute of Fashion Design, led by a French-educated designer. Despite having already completed one bachelor’s degree, and undeterred by the fact that she was older than many of the other students, Khan took the entrance exam and enrolled in its very first class, with financial support from her brother, Johnny.

Khan knew she was entering uncharted territory when she graduated, so she took every opportunity that came her way. She taught at local textile and vocational schools and consulted for multinational companies producing clothing for brands like Wrangler and Levi’s. She then started her own business, based on her passion for high fashion: designing custom-made wedding gowns.

Then, unexpectedly, she became a morning-television staple, having caught the eye of television producers after doing a short TV segment about pattern-making. “One thing led to another, and I became a prominent morning-show anchor, five days a week,” Khan says.

Her ability to multitask is remarkable, even to her friends. Ayesha Shafi, CEO of the Radio Azad network, where Khan has a show today, says, “I think her day has 48 hours. The way she is able to balance all her different responsibilities; it is not easy.”

Khan’s early wedding-gown business was her first foray into empowering women. She opened a small factory in Karachi to produce her designs and today has 12 employees — all from impoverished backgrounds and some, refugees. Khan offers training, bonuses and maternity leave, benefits available to few working women, especially factory workers.

“I want these girls to have economic sustenance, social growth and mental growth,” says Khan, who hopes to expand into menswear and seasonal collections so she can increase the number of women she employs.

No easy answer

Back in 2010, a tragedy in Hunza Valley reconnected her to her ancestral homeland. A massive landslide destroyed the village of Attabad and others downstream, not far from where she spent her childhood summers. Dozens died and thousands were displaced, forcing families to find new means to earn a living.

The Aga Khan Foundation, a nongovernmental organization (NGO) with a strong presence throughout South and Central Asia, reached out to Khan, who had always proudly proclaimed her Gilgit-Baltistan roots. The foundation asked her to help train women interested in becoming tailors, since she had a teaching background and speaks the local language. Over the next eight years, she took on skills-training and artisan-support programs for large NGOs, including BRAC Pakistan, and managed a World Bank grant at the Indus Heritage Trust. Khan trained over 5,000 artisans and helped create better local and international markets for their products.

Throughout this period, she was able to continue her fashion design and television work, thanks to supportive female bosses. But she felt increasingly drawn to the women and girls in the northern villages, where she felt she could make a bigger difference.

“There was a point where I had to make a choice,” she says. “Should I quit television and pursue my education to become a development practitioner, and leave everything behind?”

There was no easy answer: Her friends and family asked if she was having a midlife crisis, and she faced criticism for walking away from what appeared to be a glamorous, successful life.

“I remember submitting a proposal for program amendments with the World Bank grant, and it was dismissed because of my qualifications, since I had gone to fashion school,” Khan says. She wanted to be taken more seriously. That’s when she decided to come to the Heller School.

‘Heller gave me the courage’

In 2017, Khan created the Empyrean Foundation with her sister, Nadia, and her brother, Johnny. Their original focus was on female artisans living in extreme poverty in South Asia, teaching them to take traditional handicrafts and embroidery to market, and training them in fashion design and textile creation to start small businesses.

But the Empyrean Foundation quickly moved beyond its original focus — providing garment-industry skills to women artisans in South Asia — and adopted a nimble, hands-on approach.

“If I was working for another organization, I would not be able to create all these programs,” Khan says.

It was just one year later that Khan enrolled in Heller’s MA in Sustainable International Development (SID) program. She was drawn to Heller’s welcoming environment, where nobody remarked on her accent, and its ideal combination of international development and social entrepreneurship courses, which gave her the grounding she needed to take her Empyrean Foundation to the next level and expand the reach of her work.

“Heller gave me the courage to do hands-on things in the field,” says Khan. “What I’m doing now is enhancing what I learned with real-world experience.”

“Ambreen brought a strong voice as a woman from a part of the world where women have to fight through a lot of obstacles to develop their own voices,” says Joan Dassin ’69, then-director of the SID program and Khan’s academic adviser. “I wish we had more students with artistic inclinations, like Ambreen. There’s room in this field for people to pursue all types of activities, even music or dance, because they can generate income and employment.”

For her master’s practicum, Khan worked for Proyecto Inmigrante, an outreach project in Texas. The experience gave her insight into the experiences of those trying to navigate the complicated U.S. immigration system, and opened her eyes to how she might expand her foundation not only in South Asia but also within the United States.

When Khan graduated from Heller, she moved to the Dallas-Fort Worth area, where she met her husband, immigration attorney Bhavik Amaidas. “We got married in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic over a Zoom call,” recalls Khan. “The judge allowed five people to be on the call, and due to the shutdown, we couldn’t invite anyone else. It was hilarious, as the wedding was six-and-a-half minutes long.”

In Texas, Khan realized that the recent influx of Afghan refugees could also benefit from her foundation’s work, and in addition to collecting household items to donate to refugee families, she developed a program to train women in dressmaking. Khan also piloted an online program for domestic violence victims in the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex to learn graphic design, spurred by her sister and co-founder, Nadia, a graphic designer.

As COVID-19 brought the world to a standstill, the Empyrean Foundation’s agility became even more important. “Where bigger organizations need more time to plan and get approval, we can take these liberties and meet the immediate need,” she says. For example, when COVID-19 disrupted supply chains, Khan and her local consultants created a program to teach women in Gilgit-Baltistan to stitch reusable cloth sanitary pads, providing both a livelihood for the women and a way for girls to continue attending school during their menstrual cycles.

Khan’s brother and co-founder, Johnny, says, “We’re immensely proud of Ambreen. She has such a passion for empowering women, and young girls can look at her and see the possibilities when you work hard and have tenacity.”

Creating a multiplier effect

Khan continues to raise her profile as a designer, with brides from Saudi Arabia to Canada requesting her services, and hopes the increased visibility will help her better advocate for overlooked populations. One way she’s doing that is through her weekly show on Radio Azad, a South Asian entertainment station that broadcasts locally in Texas and globally online. She addresses topics that are often taboo, such as LGBTQ+ rights, using her platform to open the minds of more conservative listeners.

“She is able to tackle these difficult issues by making the shows fact-based, logical and very empathetic,” says Radio Azad CEO Shafi. “She is able to see things from different viewpoints, outside of one’s own bubble. Ambreen is just a trailblazer.”

Though her road to development work has been unusual, Khan has no regrets about her circuitous path. She’s eager to expand her impact beyond her homeland of Pakistan and her new home in the United States.

“I see myself becoming a better activist for women,” she says. “I envision my foundation and my social enterprise growing. If we can get these girls to train more girlsfrom humble backgrounds, we can create a multiplier effect in these communities.”