By Chris Carroll

Active for years in social justice campaigns ranging from vigils for AIDS victims to demonstrating against apartheid, Elizabeth Horton Sheff was less focused on a problem that hit closer to home—the unequal education opportunities afforded children in the Hartford, Connecticut public schools, where her two children were enrolled.

That changed during a local church meeting one night in early 1988. Horton Sheff listened with growing shock to statistics quoted by the group of civil right lawyers that had arranged the meeting: Nearly three-quarters of Hartford’s fourth-graders barely qualified as remedial readers—a figure that dipped into the single digits for many nearby suburban school districts.

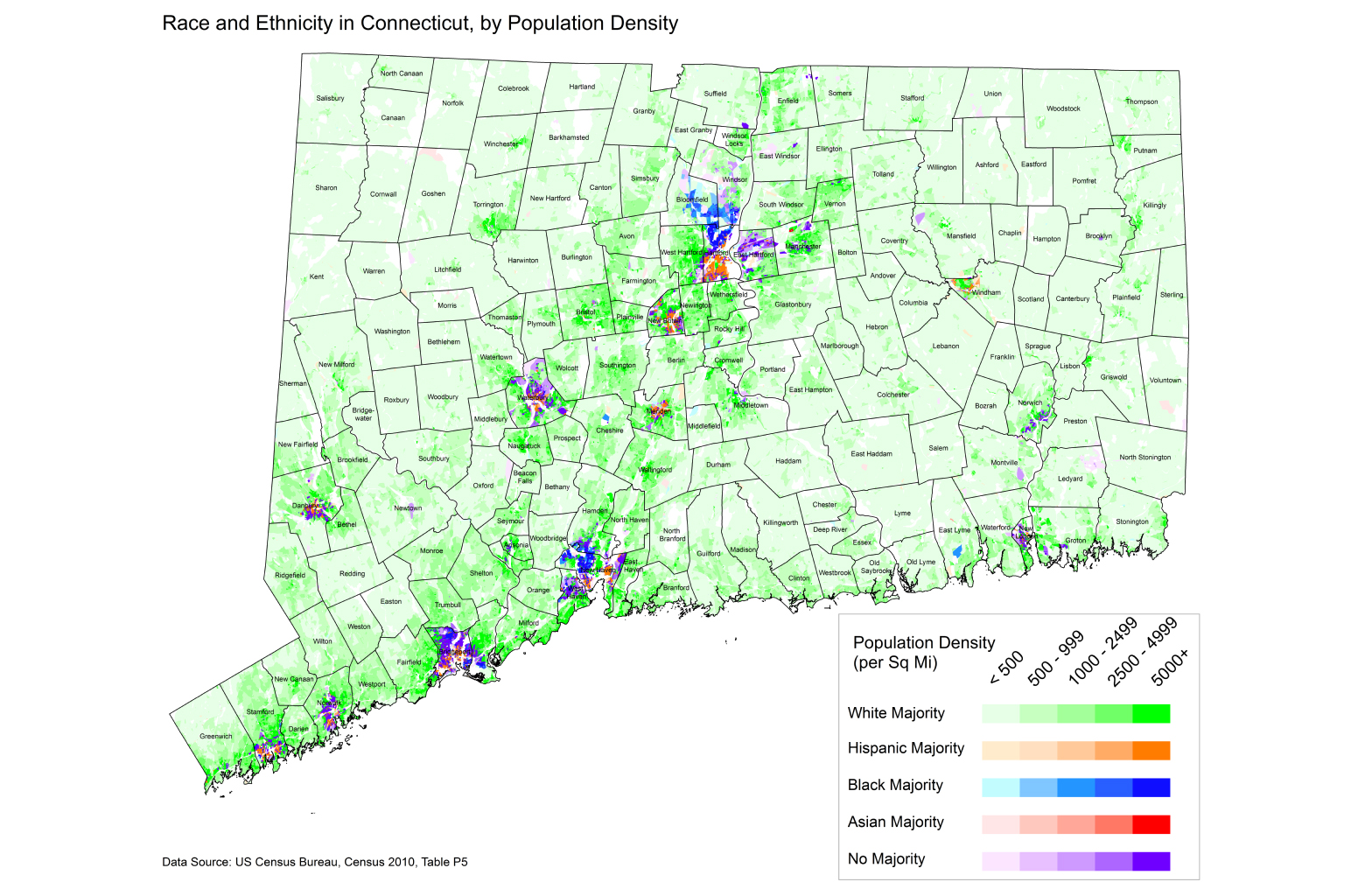

Another group of numbers put it all in maddening perspective for Sheff, an avid reader who could hardly imagine life without literacy: In Hartford schools, more than 90% of children were Black or Latinx. In surrounding districts with high test scores, students of color generally constituted less than 10% of the population.

“The realization I felt that night will stay with me for life—I was simply dumbfounded,” Horton Sheff says. “It wasn’t 74% of the children failing, but the system failing 74% of the children.”

The following year, her fourth-grade son Milo became the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit that would eventually make its way to the Connecticut Supreme Court and result in the landmark Sheff v. O’Neill ruling in 1996, affirming that children in the state have a right to equal education unmarred by racial and ethnic segregation.

Milo himself was an enthusiastic participant eager to help set things right, his mother remembers. “He thought it would be something like a Judge Judy episode—go in, present your case and come out 30 minutes later with a victory,” Horton Sheff says, acknowledging that despite the ruling, the pace of progress has been slow. “But it’s been 30 years, and in many ways, we’re still fighting the same fight.”

Connecticut’s nickname, “The Land of Steady Habits,” was likely coined in the early 19th century to describe a sensible place where officials and policies didn’t change with the wind. The sobriquet still fits, but in a darker sense, writes Susan Eaton, director of the Sillerman Center for the Advancement of Philanthropy, in her new report, “A Steady Habit of Segregation: The Origins and Continuing Harm of Separate and Unequal Housing and Public Schools in Metropolitan Hartford, Connecticut.”

Designed to help guide local and state policymakers, politicians, educators, nonprofit organizations and philanthropic bodies seeking change, Eaton’s report reaches back to the 1830s to show the roots of the stark racial and ethnic segregation that exists, with about 70% of the state’s people of color clustered in just 15 of 169 Connecticut cities and towns.

It’s not an accident of history, Eaton writes, but a system engineered over decades and still maintained in many ways even now. The result of this segregation is deeply disparate access to opportunities and outcomes, resulting in fewer educational opportunities, access to healthy recreation and food, less wealth due to constrained housing choices, lower quality of public services, less access to transportation and fewer social networks connected to job opportunities.

“My goal for the report was to bring everything together in one place to show how segregation is rooted in racial discrimination and that it misshapes a region and creates deeply unequal opportunities and life chances for human beings based upon race,” says Eaton, who began her career as an education reporter in Stamford, Connecticut, in the 1980s before earning a doctorate from Harvard’s Graduate School of Education. She went on to write several books about de facto segregation of schools, including a book-length narrative account of the Sheff v. O’Neill litigation, published in 2007, “The Children in Room E4.”

“Susan’s work and the work of other policy-minded scholars in this area helps us understand why things are the way they are in Connecticut today,” says Kate Szczerbacki, PhD’18, the director of strategic learning and evaluation at the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving. “We’re dealing with structural racism and systems of white supremacy … (and) this work helps with that naming of what is actually happening.”

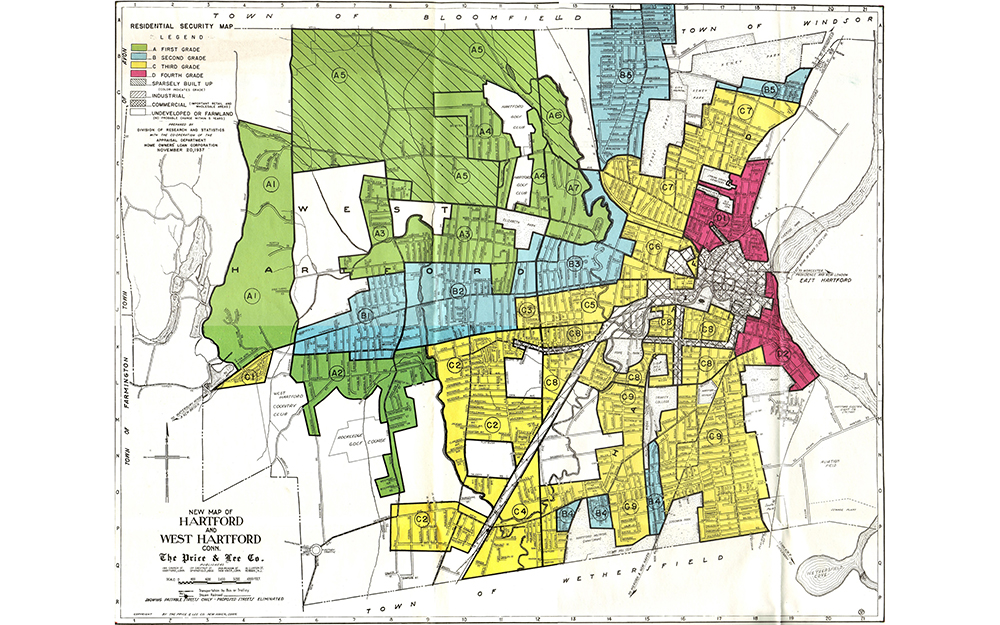

Mutually reinforcing barriers—exclusionary school district boundaries, federal and state government housing practice and policies, and restrictive local planning and zoning polices—have long been the foundation of segregation in the Hartford area. What’s maintained them, at least since the early 1960s, Eaton says, is lingering race and class discrimination and staunch resistance to greater regional oversight in school and housing practice and policy.

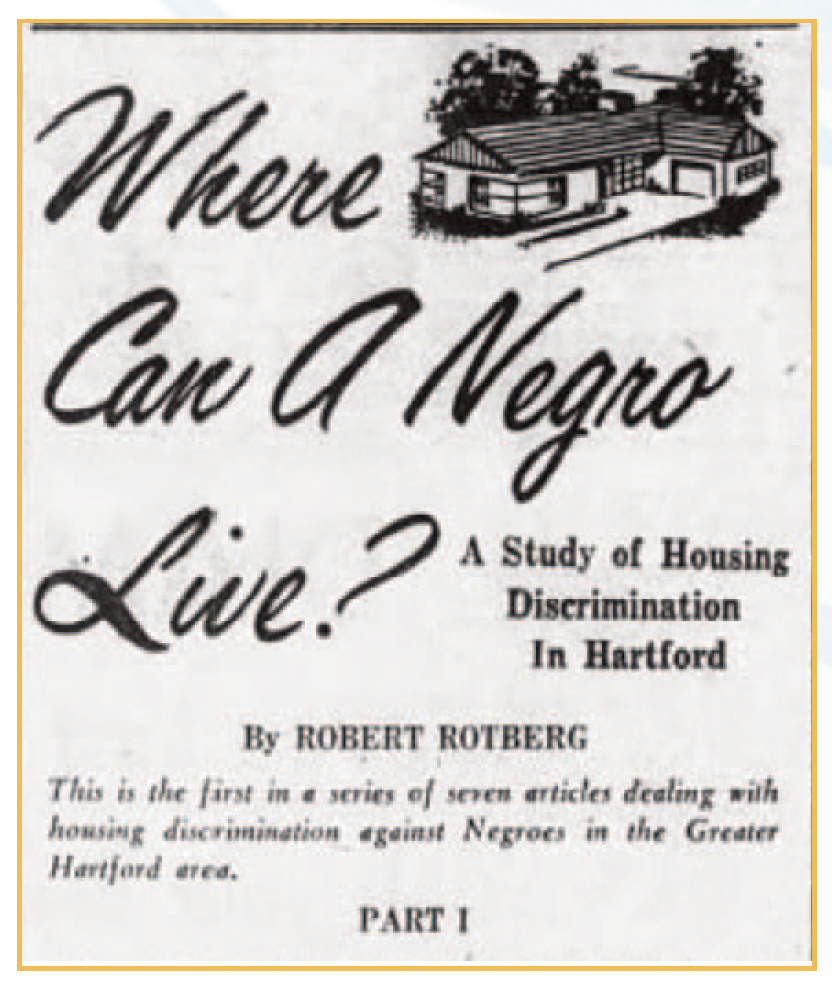

“It surprised me when I found all these things were up for debate and discussion decades ago … there were serious people talking about it and raising concerns about it, including African American parents, legislators and scholars at Trinity University,” Eaton says. “Segregation in schools and housing was not discovered with the Sheff v. O’Neill case in 1989.”

As local leaders watched accelerating white migration to the suburbs in the early 1960s, the Hartford Board of Education commissioned a report from Harvard scholars. It recommended regional school districting as a means to head off worsening segregation while diffusing white flight, which the group predicted would result from trying to fix problems within the boundaries of existing districts.

The Harvard group’s suggestions would have required state legislation and were never acted upon, although a relatively small program known as “Project Concern” sent limited numbers of Hartford students to suburban schools. Within the city, as the authors predicted, integration attempts sparked angry reactions from white residents who responded with complaints about socialism, and in some cases, with open racism. Meanwhile, in 1967, a bill to create a regional housing authority to place subsidized housing in the suburbs led one to Glastonbury representative declaring, “We are violently opposed to this.”

Suburban residents who wanted to prop up the racial status quo knew that strict control of where people can live is the key, says John Brittain, a prominent civil rights attorney who, while a professor at the University of Connecticut School of Law, was part of the counsel team that brought the Sheff v. O’Neill lawsuit.

“Housing segregation is the overriding, number one cause of segregation in schools,” says Brittain, now a professor of law at the David A. Clarke School of Law at the University of the District of Columbia. “And the strong local control that exists in Connecticut maintains the racial zoning that maintains the de facto segregation.”

While Connecticut may be a Northeastern state that votes reliably blue, it competes with the Deep South on some metrics that relate to housing segregation. For example, it trails only Mississippi in how much of its affordable housing is concentrated in low income areas, according to a 2015 federal report, Eaton writes. Twenty-five of the state’s 169 municipalities allow the construction of no new affordable housing, while most limit multifamily housing to certain zones and require special permitting to build it.

The result: Disproportionately, people of color looking for greater economic opportunity are often stuck in places with little to offer, while even the towns and suburbs with restrictive zoning suffer from a lack of local labor and talent in their own economies, all due to locked-down local control.

“This is a little postage stamp of a state, but it functions like 169 sovereign entities,” Horton Sheff says.

Solutions to school desegregation in the Hartford area are proceeding, albeit slowly, via a series of plans that stem from the 1996 Connecticut Supreme Court decision. Dozens of magnet schools have opened that draw students from both Hartford and surrounding areas, and Horton Sheff, who remains active on a range of civil rights issues, frequently is stopped by parents thanking her that their children have the opportunity to obtain high-quality education.

“And sometimes I’ll get stopped and laid out by a person of color who hasn’t been successful in the lottery for admission, or I’ll get laid out by white people who want to keep Jim Crow alive,” she says. “It’s been bittersweet, but the fact that we have improved thousands of children’s lives over the years makes it all worthwhile.”

Similar plans that cut across district lines to create magnet schools are rare around the country, but highly successful where they exist, Brittain says. Even in Connecticut, the 1996 Sheff v. O’Neill ruling in favor of civil rights plaintiffs applies only in Hartford, although other major cities could operationalize it if they chose. The value of Eaton’s decades of work, he says, lies in assembling a number of threads leading to an inescapable conclusion that should drive civil rights advocates to take that kind of action: “You can see the racial isolation that exists if you just look,” he says.

Fair housing advocates are still seeking a big win that’s been a long time coming. The state legislature recently passed a bill that institutes a number of lesser reforms to address housing disparities, but blocked a statewide remedy known as “Fair Share” that would require municipalities to come up with enforceable plans to promote affordable housing development.

Resistance is so entrenched in many areas that trying to work out solutions on a case-by-case basis is an intractable problem, says Erin Boggs, executive director of the Open Communities Alliance, a Connecticut civil rights organization that works to give people housing choices.

“There was a case where a town planner actually told a developer we don’t have sewers on purpose so we don’t have to have affordable housing,” Boggs says. The advantage of the Fair Share bill was that “we don’t actually have to dig into all the nitty gritty details on what towns are doing. It just says ‘Here’s your number, town. We don’t care how you do it, but the number of affordable housing units you have to plan and zone for and promote over the next 10 years is 542,’” she says.

Though she and other advocates now have to return to the drawing board, she says Eaton’s report delivers important historical context at a time when many people seem ready to rethink de facto racial exclusion.

“Something has happened since the murder of George Floyd and all that followed,” Boggs says. “We’ve been inundated with calls from people in white suburbs interested in fostering changes.”

While legislative efforts might take longer, philanthropic organizations could move more quickly with financial support, say Eaton and Szczerbacki. Funders could strengthen programs that provide “mobility counseling” to families seeking to escape racial segregation, as well as invest in community groups in communities of color advocating for greater equity.

The upsurge in society’s willingness to acknowledge structural inequality following the Black Lives Matter movement gives Eaton hope her report will have an impact as education and fair housing advocates fight the latest battles in a long conflict.

“I think the national consciousness has changed somewhat—but we’ve had similar changes before that didn’t last,” Eaton says. “I hope this time, we all decide to learn from history, and understand that a problem created collectively needs to be solved collectively.”