The U.S. economy has been in recovery from the Great Recession for over 10 years—a decade of unprecedented economic growth in which the country boasted net positive job growth every single month since October 2010, and a sub-4% unemployment rate since July 2018.

Any introductory economics classroom might consider this a tight labor market: As the economy grows and the supply of available labor falls, wages and workplace conditions should improve. But, as economist and Heller School Dean David Weil knows all too well, that’s not happening.

“This is an unprecedented economic recovery, but it’s also unprecedented how little, in real terms, wages have responded,” says Weil.

“Something’s going on out there.”

Wage stagnation in the U.S. is extremely well documented, but to the frustration of Weil and many others, the causes remain poorly understood. To gain a new perspective on this persistent issue, Weil has convened a research team to investigate two additional factors that influence wages: wage norms and labor market shocks.

“Wage norms can be understood as what people feel is a fair wage to be paid for a given job,” says Weil. These wage norms and other labor market conditions have eroded in recent decades, he adds, as the federal minimum wage stagnates, union density drops and more workers enter the “fissured workplace” as independent contractors, rather than employees.

“In traditional economics, we think about a ‘reservation wage’ as the minimum rate required to convince an economically rational person to accept a job offer. That wage rate is partly affected by the value of workers’ other options, such as alternative employment, or the value they place on non-work hours,” he says. “But, often less considered in formal economic analysis, a reservation wage is also strongly affected by the perception that the wage is fair or unfair based on lots of factors, including family background, community standards, and what peers in the workplace and relevant labor market are being paid.”

Weil and his team are interested in how social factors—such as demographics, union density, and the depth and breadth of social networks—interact with wage norms in different labor markets. One of the ways economists study wage norms is to find something that disrupts them. “A shock to the system,” says Weil. “Or actually, in this case, three shocks.”

The three shocks that Weil and his team plan to examine each represent a sudden increase to the minimum wage in specific labor markets. The study, which is jointly funded by the Russell Sage Foundation and Equitable Growth, is co-led by labor economist Ellora Derenoncourt, a postdoctoral research associate at Princeton University. Weil and Derenoncourt are joined by Heller School colleague Clemens Noelke, a scientist at the Institute for Child, Youth and Family Policy, as well as PhD and undergraduate student researchers from across the Heller School and Brandeis.

Derenoncourt says, “This is a dream team. I feel so positively about this collaboration experience. We’re aligned on the broader goal of making things better for low-wage workers and addressing inequality, which is such a critical issue right now.”

Though they are still in the first phase of this study, the preliminary results are promising. For the first shock, they’re looking at labor markets where large employers—such as Amazon and Wal-Mart—voluntarily raised their in-house minimum wage. Using a dataset containing millions of job postings from Burning Glass Technology, they’ll then look to see whether other companies in these labor markets raised their entry level wages in response to these high-profile increases.

Says Derenoncourt, “In the national conversation about moving toward a $15 minimum wage, we’ve seen a few employers take on some of these policies internally. Amazon is probably the biggest example of that. But we actually don’t have any evidence of whether those employers actually do what they say and change their polices, first of all, and secondly we don’t know the spillover effects of that policy change in the broader labor market.”

Weil adds, “It’s early still, but our initial results indicate that yes, these big companies do have an impact on the wage behavior of other employers. They don’t sit quietly by when a company like Amazon decides to pay $15 an hour.”

Once this initial analysis is complete, the team will then look at the social and demographic characteristics of these labor markets to see whether they had an impact on the extent of these wage shocks.

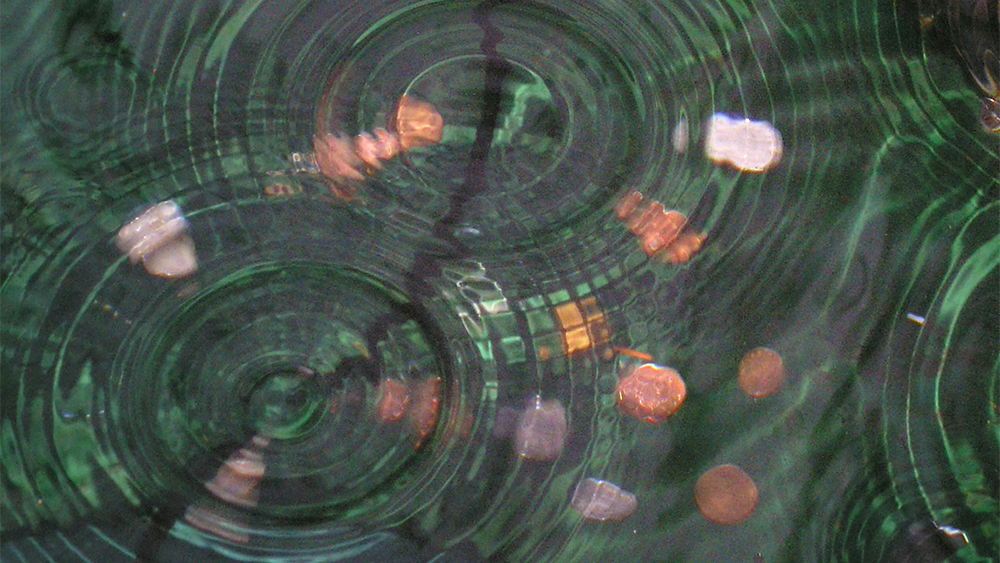

Weil describes this two-part research question as, “Plunking rocks and studying the ripples. You can plunk a rock into water or into pudding, and the waves will dissipate differently. We’re looking to see whether the rocks—the wage shocks—have an effect on the labor markets. And if there is an effect, it will be felt differently in communities with different social networks and norms, union density, other measures of social capital—water versus pudding.”

The second shock the team plans to study stems from Weil’s prior work as head of the Wage and Hour Division at the U.S. Department of Labor. In 2014 President Obama signed an Executive Order raising the minimum wage for federal contract employees to $10.10 an hour, impacting hundreds of thousands of workers. Weil and his team will examine the effects of this shock on wage norms in local labor markets, and whether the social composition of those markets played a role.

The third and final shock reflects a direct attempt to change wage norms—the Fight for $15 advocacy campaign from 2014-2015. Fight for $15 pushed for state-level change, contributing to minimum wage increases above the federal minimum wage in 29 states and the District of Columbia. For this shock, the team will examine whether the Fight for $15 campaign affected local wage norms directly by changing employer behavior in areas where the campaign was particularly active, as well as by amplifying the impact of the other shocks studied by the team.

Jenny Yang, a Heller Board of Advisors member and former commissioner of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC), says, “This research provides a powerful foundation for understanding the policies that matter, to help boost the pay of our lowest-wage workers.”

Weil and his team hope to publish their findings in peer-reviewed publications in the coming months. “But because we’re doing this research at Heller,” he adds, “We also ask ourselves: So what? Really, the point of this research is to understand how wage norms can change, and by extension, what tools we can use to raise wage norms beyond policy changes.”

“Unlike other markets, the labor market is inherently unbalanced in terms of bargaining leverage: Low-wage workers and contract workers in fissured workplaces have comparatively less power. That’s why we have labor market protections in the first place—we have to protect those workers because many employers, left to their own devices, won’t do it.”

Labor attorney and former Massachusetts Secretary of Labor and Workforce Development Joanne Goldstein, says, “The intractable problems with the fissured workplace include the inability to identify an employer and the lack of accountability for the workers’ wages. Dean Weil’s research provides the context for how to address and resolve these issues.”

Though this study is focused entirely on wage norms, Weil also hopes that what they learn might illuminate other kinds of norms—and ways to change them. He says, “In the long term, I’d like this research to help us understand other workplace norms. How do we convince workers that they have a right to complain when their rights are violated? Or to intervene when someone in their workplace is sexually harassed or faces racist behaviors? Norms are powerful, and they reflect what people view as fair, but we know very little about how to change them. If we understand how workplace norms evolve, we can contribute to building fairer workplaces for everyone.”