By Bethany Romano, MBA'17

In the world of elite mountaineering, Daniel Mazur, PhD’00, is a celebrated alpinist and trip leader. A veteran climber, he’s summited virtually all of the world’s tallest peaks and has led 12 expeditions to Mount Everest. In addition to these accomplishments, he’s known for having rescued several fellow climbers on Everest, including a high-profile incident in 2006 that landed him in newspapers across the country.

Over the decades, he’s become deeply involved as a philanthropist in the Everest region, supporting critical sustainable development projects alongside indigenous people in the area. His top philanthropic goal today is to construct a solar-powered biogas facility to treat the thousands of pounds of human waste left on Everest each year.

“I got into the social aspect of my work,” he says. “I wanted to take the concept of giving back that I learned at Heller, and bring a certain amount of study to it, to identify needs and look at policy. I started to spot areas where maybe I could do something helpful, collaborating with local people to work toward common goals. I do a lot of that now. And that’s all because of Heller.”

Social Work Beginnings

Growing up in the flatlands of suburban Illinois, Mazur’s earliest exposure to mountains and wilderness was through his grandfather’s stories. “My grandfather was my hero,” says Mazur. “He homesteaded in Montana in the 1920s, and he was a Boy Scout for 50 years. I always just thought he was the greatest guy.”

Though Mazur’s grandfather passed away when Mazur was just 10, those stories of homesteading in the shadow of the Rockies inspired him to attend the University of Montana, where he began climbing mountains and glaciers.

He also earned a bachelor’s degree in social work, citing his upbringing as inspiration. “My parents were both PhDs and were active in their community, so I learned about the importance of public service and education from a young age,” says Mazur. The world of social work intrigued him enough that he quickly sought a graduate degree in the field.

“I was interested in what causes social issues, what contributes to them. So I started looking at graduate schools, and Heller popped out as a really cool option,” he says. “I was really impressed with the people, the teachers and students I met at Heller.”

As a doctoral student in the 1990s, Mazur pursued questions around affordable housing for the elderly. He was interested in the importance of extended family and in policies that could foster affordable housing in the U.S. for grandparents as they age. His classmate Howie Baker remembers him as a “thoughtful and non-judgmental person, always very positive about our work.”

But earning a PhD is not a quick endeavor — and the mountains were calling. “Summers I would go away and climb mountains, first in Alaska with friends, and then just bigger and bigger mountains every year, until eventually I ended up climbing Everest,” Mazur says.

Partway through his doctoral degree, he took several years off to seriously explore his options as a professional mountaineer. He moved to England and split his time between university classes and climbing. Eventually, he had a “lightbulb moment” in a class in England. “I discovered how the British manage affordable housing for older people, and I decided I wanted to weave their idea together with U.S. housing policy. That idea really intrigued me — enough that I had to get back to Boston right away.” He rushed back to Heller and completed his dissertation within three years.

Professional Summit Guide

After earning his doctorate in 2000, Mazur turned to professional climbing as his full-time job. “I saw that I could take other people up there and share my love of it. I got into leading these expeditions and earning my living at that, paying all my bills,” he says. For the last 16 years, he’s been an expedition leader for Summit Climb, guiding groups to scale mountains like Everest and K2 every year.

Though his home base is Olympia, Washington, his work regularly takes him to Tibet, Nepal, Pakistan, India, China and more. He describes his work as his passion, but he’s quick to add that “the responsibility is huge, and it’s stressful. It’s great to be with people who are on vacation, but it’s a risky and dangerous thing. I don’t want to discount that or take it for granted.”

Mazur’s climbing adventures have been chronicled by many news outlets, from National Geographic and The New York Times, to NPR and NBC. He’s lived through avalanches and earthquakes, injury and frostbite. He’s known many climbers who have died, and he’s had a few close calls himself. The first time he ever climbed Everest was on an unplanned trip with someone he barely knew — a Russian climber who neglected to inform him that he had only one lung (he collapsed and had to be rescued on the descent, but survived).

The most famous of Mazur’s adventures is the 2006 rescue of Australian climber Lincoln Hall, whom Mazur discovered at 28,000 feet after Hall had been left for dead the night before by his own party. Mazur and his team radioed for help and sacrificed their own chance to summit Everest, sharing their oxygen and supplies with the disoriented Hall and eventually getting him back to base camp for medical care.

When asked about the climbers Mazur has rescued over the years, he expresses characteristic humility. “If I see someone that needs help, I was always someone that couldn’t walk away. But everybody’s different. We’ve all been in a car driving down a highway and seen a car in a really bad accident. Sometimes you stop and sometimes you don’t. Sometimes traffic is bad, or you see an ambulance already there; it looks like it’s covered. It’s hard to know if you can actually help. It’s tricky.”

In fact, despite having led 12 expeditions to Everest — many of them successful — he’s only summited once himself. “Every time I go up there, I keep getting involved in looking after our own team members and members of other teams, rescuing people, and helping people who are not feeling well to get back down,” he says. “I keep saying I will go to the summit, and then I get sidetracked helping people.”

Fostering Development in the Everest Region

There are two throughlines in Mazur’s career: summiting the world’s tallest mountains and helping the people he encounters along the way. In addition to rescuing fallen climbers, he’s deeply involved in supporting long-term sustainable development projects in the Everest region.

Mazur notes that his initial efforts at philanthropy weren’t his most successful. He recalls donating computers to a government office that issues climbing permits whose equipment was sorely outdated. He succeeded in procuring and installing some used laptops, and then promptly received a sharp rebuke from the Sherpas he was working with.

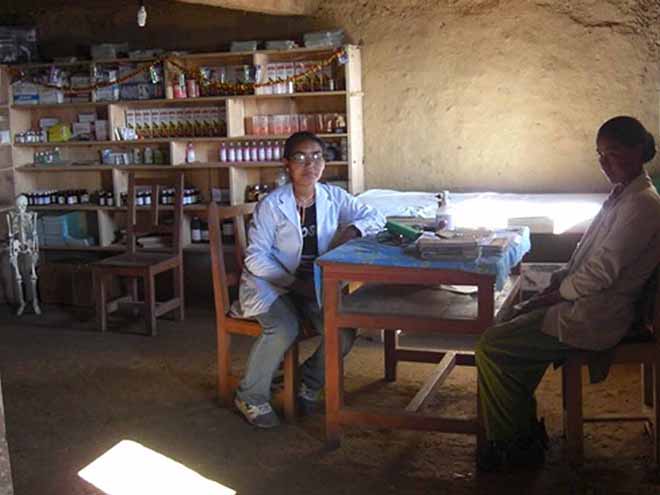

“They were like, ‘What are you doing? The people in our village don’t have any health care. There’s nowhere for them to go when they get sick. Why don’t you work on that instead?’” he remembers. “So I went to visit their village, which I’d never been to, out in a very remote area, and there were 4,000 people living there with zero access to health care within a two- or three-day walk.” Mazur worked with his Sherpa colleagues to drill down to the main issues and devise solutions: raising funds to bring in medical supplies, training local people to become health workers and getting doctors to make regular visits to the village.

“That’s how it all started,” he says.

In 2003, Mazur and that same group of Sherpas founded the Mount Everest Foundation for Sustainable Development (MEFSD), a registered nonprofit in Nepal. “They do tons of different projects. They have the knowledge on the ground, local skills, knowledge of the local government. They can get stuff done,” he says. Mazur brings ideas to the table as well as his capacity as a fundraiser: He regularly gives slide shows and talks around the U.S. and U.K. to raise awareness and funds for MEFSD projects.

He also raises awareness through his day job as an expedition leader, making sure that tourists and climbers are aware of the health care and education needs of the local mountain communities, and providing an opportunity for them to give back. Of his clients, he says, “When you see a problem, I think it can be really hard to know what to do. And as a tourist, you’re only visiting for a short time, or the problems may not be obvious to you, or you’re on vacation and that’s just not why you’re here.

“But I think all of us have the ability to help others, inside ourselves. And all of us have the ability not to help others. We just have to make the ability to help others come to the fore, and pop out.”

The MEFSD and Mazur have implemented many projects in the region, including developing schools and clinics in rural areas, providing free Sherpa climbing training programs and renovating cultural sites such as the Deboche convent, a historic and culturally significant building that was severely damaged by an earthquake in 2015.

Today, Mazur’s priority is the Mount Everest Biogas Project, a much-needed treatment plant to manage the massive problem of human waste deposited on the mountain every year. He’s partnered with Kathmandu University, Seattle University and Engineers Without Borders to develop a design, secure government permits and conduct site visits. At the moment, he and his partners are fundraising to secure resources to implement their design.

For these and other philanthropic projects in the region, Mazur was presented the Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Medal in 2018 “for remarkable service in the conservation of culture and nature in mountainous regions.” The medal is awarded by Mountain Legacy, a Nepali nonprofit dedicated to the stewardship of mountain landscapes, ecosystems and communities.

“Like [Sir Edmund] Hillary, Dan Mazur has been able to marshal an impressive array of resources, through a combination of tireless off-season speaking engagements and a variety of service treks,” says Seth Sicroff, project director of the Sir Edmund Hillary Mountain Legacy Medal.

“Although I continue to climb professionally, the facets of what I learned at Heller have always stayed with me,” Mazur says. “I’ve become more and more focused on giving back to indigenous mountain peoples living on the slopes of the peaks we climb, where local families can benefit from health care and education, cultural and environmental preservation.”

“I just love what I do. There’s so much need out there, sometimes I feel like we’re not even scratching the surface, but I’m going to keep going. And that’s what I loved about my time at Heller: that enthusiasm and care, and the way we all shared in that.”