By Karen Shih

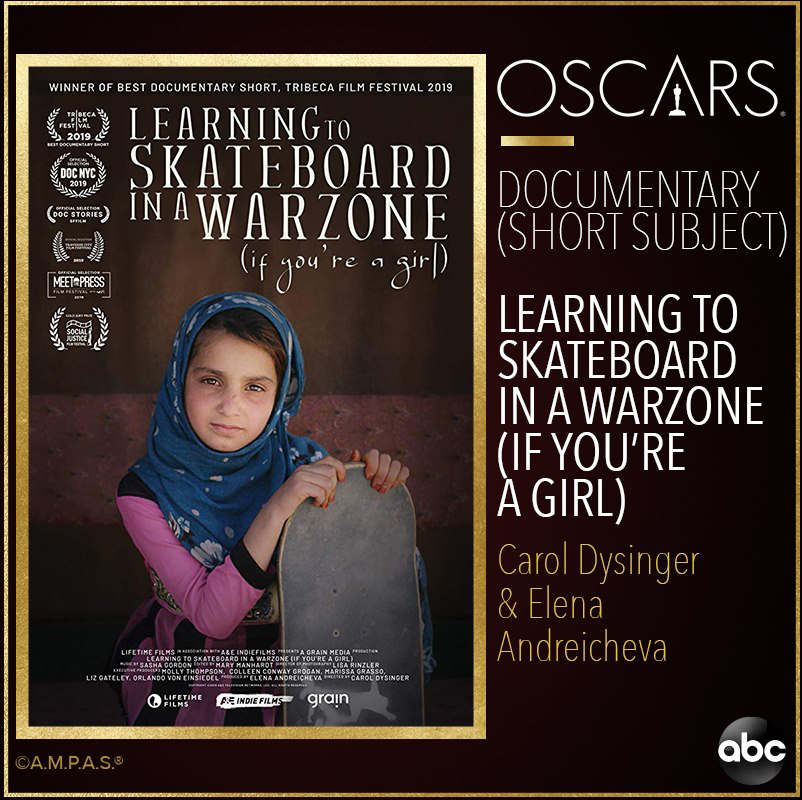

Last Sunday, the 2020 Academy Awards honored “Learning to Skateboard in a War Zone (If You’re a Girl)” with the Oscar for Best Documentary Short Subject, which features the work of Soroush Kazemi, MA COEX’21. Kazemi led the nonprofit Skateistan-Kabul as general manager for nearly four years, working with 700 children—mostly girls— to give them new educational opportunities through sports. Today, he’s studying to earn his Master’s in Conflict Resolution and Coexistence at the Heller School, planning to take his new skills back to Skateistan to expand its impact.

Q: Tell me about Skateistan-Kabul and your role with the organization.

I joined Skateistan-Kabul in 2016 as general manager. It was a dramatic change for me, because I previously worked at a think tank, but I wanted to work with children and address real social challenges: poverty, the reality of 3 million children out of school. All children deserve to receive education, regardless of their ethnicity, religion or language.

Skateistan was founded in 2009, the first indoor skate park in Afghanistan with an education component. The mission is to support street-working children—who polish shoes, wash cars, sell tea, gum and snacks, for maybe $1 USD per day—and the Skateistan goal is to get them back to school through the program.

At Skateistan, skateboarding is the hook. Once the children come to skateboard, we enroll them in education programs and classes, leadership activities and other sports, like climbing and volleyball. These activities aren’t just about sports and fun—we’re building their self-confidence. In our back to school program, we enroll street-working children in our program for one year. We cover three grades, from first to third grade, and we provide everything: free shuttle buses, lunch, snacks, and activities. We also teach them about the environment, human rights, so they can learn how to become responsible citizens. After one year, we enroll them back in public schools and track them, to make sure they continue their lessons and education.

It’s so challenging to get parents to agree to send their children to our school. The first question they ask is, “How much do you pay?” Our social workers go and talk to them about the future and the importance of education, to convince them to join our program.

Today, we serve about 700 children per week in Kabul, and even more in northern Afghanistan, Cambodia and South Africa.

Q: Why did you want to help make this documentary happen?

When I first joined in 2016, many factors were against this movie. Some colleagues believed it would interrupt class sessions, and there were challenges to film shooting inside the government compound where Skateistan is located. We worked with the government to get their permission to allow film crews who drove armored vehicles, and we had to talk to government guards every time the film crew entered the compound.

But I told our colleagues at Skateistan headquarters in Berlin, “It is the very right time to send a very different message to the world.” This is a message of hope and peace and love. That Afghanistan and Kabul are not just about explosions, suicide attacks, where females and women are second-class citizens. It is a country where people are trying very hard for change.

I worked behind the scenes to make the arrangements for shooting the film, asking for government permission. It was so challenging. The two main characters, the girls, and some instructors and teachers didn’t want to be filmed. I talked and encouraged all sides to be supportive and let the filming happen, because it was for their good and the organization.

We never thought about the BAFTAs, or Oscars. But now it’s happening! Skateistan is 10 times more famous.

Q: How did you first become interested in working for human rights?

I grew up in Mazar-e-Sharif in Northern Afghanistan. During primary school, my family and many others were forced by the Taliban to leave our homes and flee to one of the neighboring countries. We went to Iran in the hope of having a better life and to continue my studies. But soon I realized that I was not allowed to study, and I was not treated like others since I was a refugee family’s son. I didn’t give up, I started self-studying, reading newspapers and working during the day, selling pens on the street, in order to take and afford a night shift English class in a private educational center.

In the aftermath of the Taliban regime collapse we returned to our homeland. I went back to school and while I was in high school, I established a monthly paper with support of my friends. I remember that we were saving our pocket money to afford the printing cost. We wanted the youth to be heard and have our own independent voice.

We questioned social challenges, like why people don’t have equal access to education; why there was child and forced marriage; and environmental problems like air pollution and solid waste management. That led me to my first job, with the Civil Society and Human Rights network. That’s when I realized everything I was doing and talking about were all about human rights, even though I didn’t know the theories and never heard the terms human rights, democracy and so on. In that job, I traveled to each province of north and northeast of Afghanistan to launch awareness campaigns, producing radio programs and facilitating debates on human rights.

Q: What brought you to the Heller School, and what are your plans for after graduation?

I worked for 10 years in nonprofit organizations, focusing on promoting human rights. In 2014, my wife, Alia Sharifi, MA SID’16, came to Heller to study and I had the opportunity to visit her. Alia took me to some classes and I met some of her friends, including Seema Rajouria, MA SID/COEX'16, who was doing a SIDCO dual degree [MA in Sustainable International Development and MA in Conflict Resolution and Coexistence] and she introduced me to Sandra Jones [then the associate director of the COEX program]. I thought, “This is the right place for me.” I applied and received admission and a generous scholarship from Heller in 2016, but my visa was rejected three times. I never gave up, and finally, in summer 2019, I was able to secure the visa and finally joined Heller.

I love the diversity at the Heller School and Brandeis. Here, I’ve learned that it’s not only Afghanistan facing these challenges—there are other classmates from other countries in the same boat. They are all working hard to bring changes to their countries. I’ve learned a lot from my classmates and the experiences they’ve shared, which will enrich and enhance my knowledge for when I go back to the field and start stronger than before.