By Tony Moore

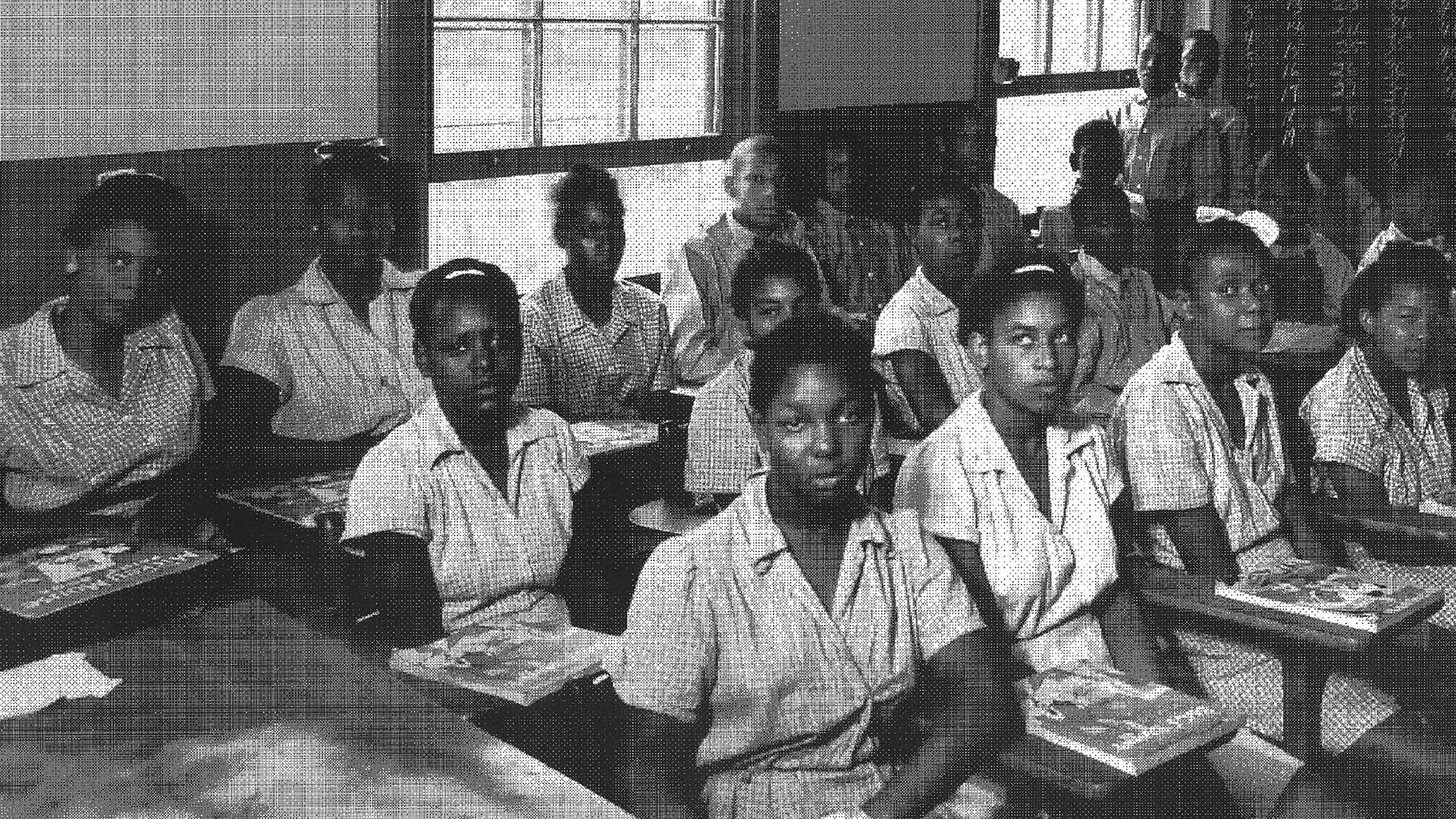

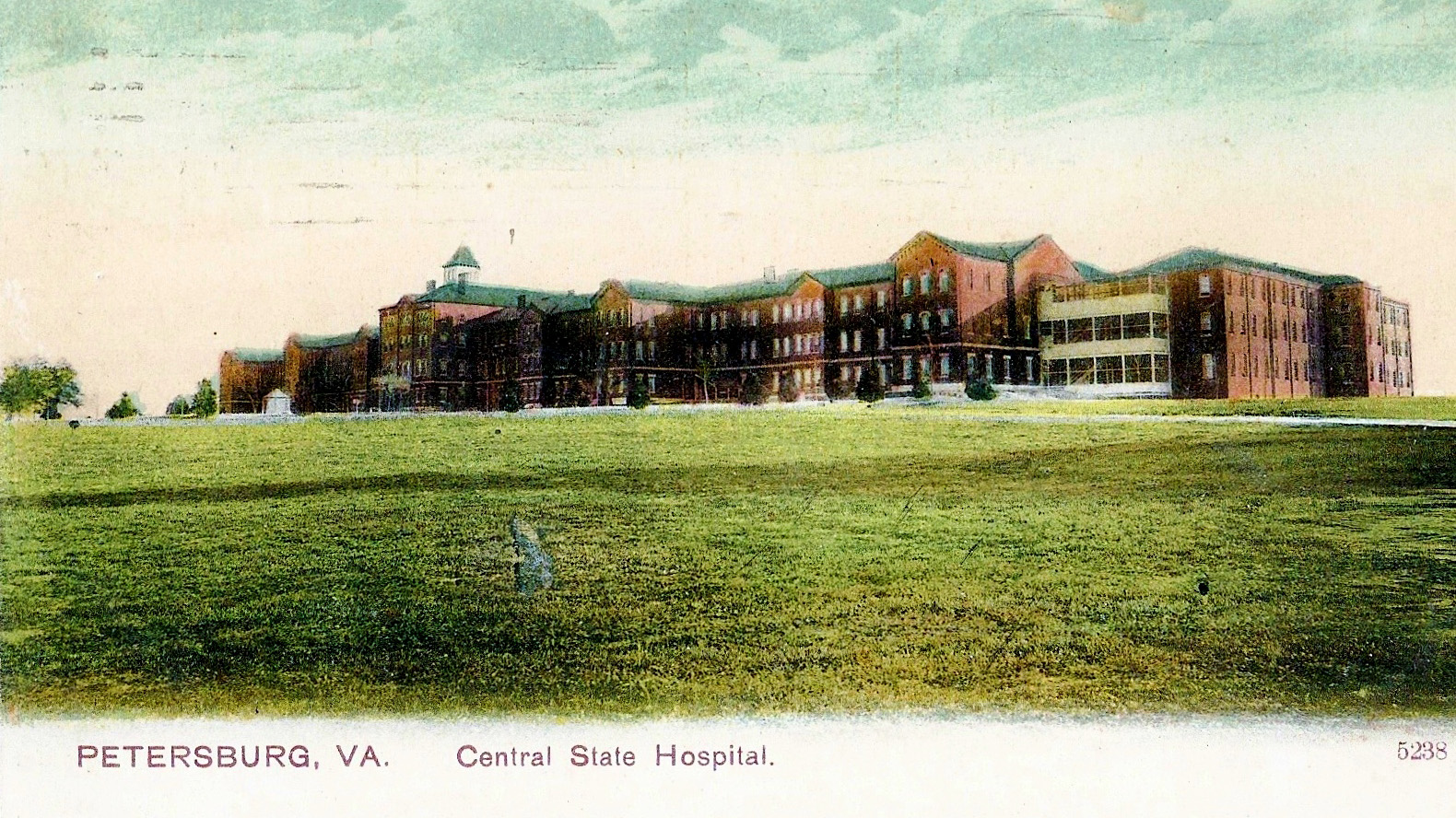

The documents were all there. Mountains of them. Tens of thousands of photographs, records and reports detailing a critical chapter in the history of African American mental health. The files sat in the Central State Hospital in Petersburg, Virginia, originally established in 1870 as the Central State Lunatic Asylum for Colored Insane. It was the first psychiatric hospital for recently freed slaves, and it had maintained stacks upon stacks of treatment records, operating policies, financial documents and more.

But there was one major problem.

The room holding all of these files lacked air conditioning. It was damp and moldy. Temperatures soared up to 130 degrees. Type was fading, pages deteriorating, images blurring. Even worse, the documents were slated to be destroyed to free up storage space. A vital treasure trove of history teetered on the verge of disappearing forever.

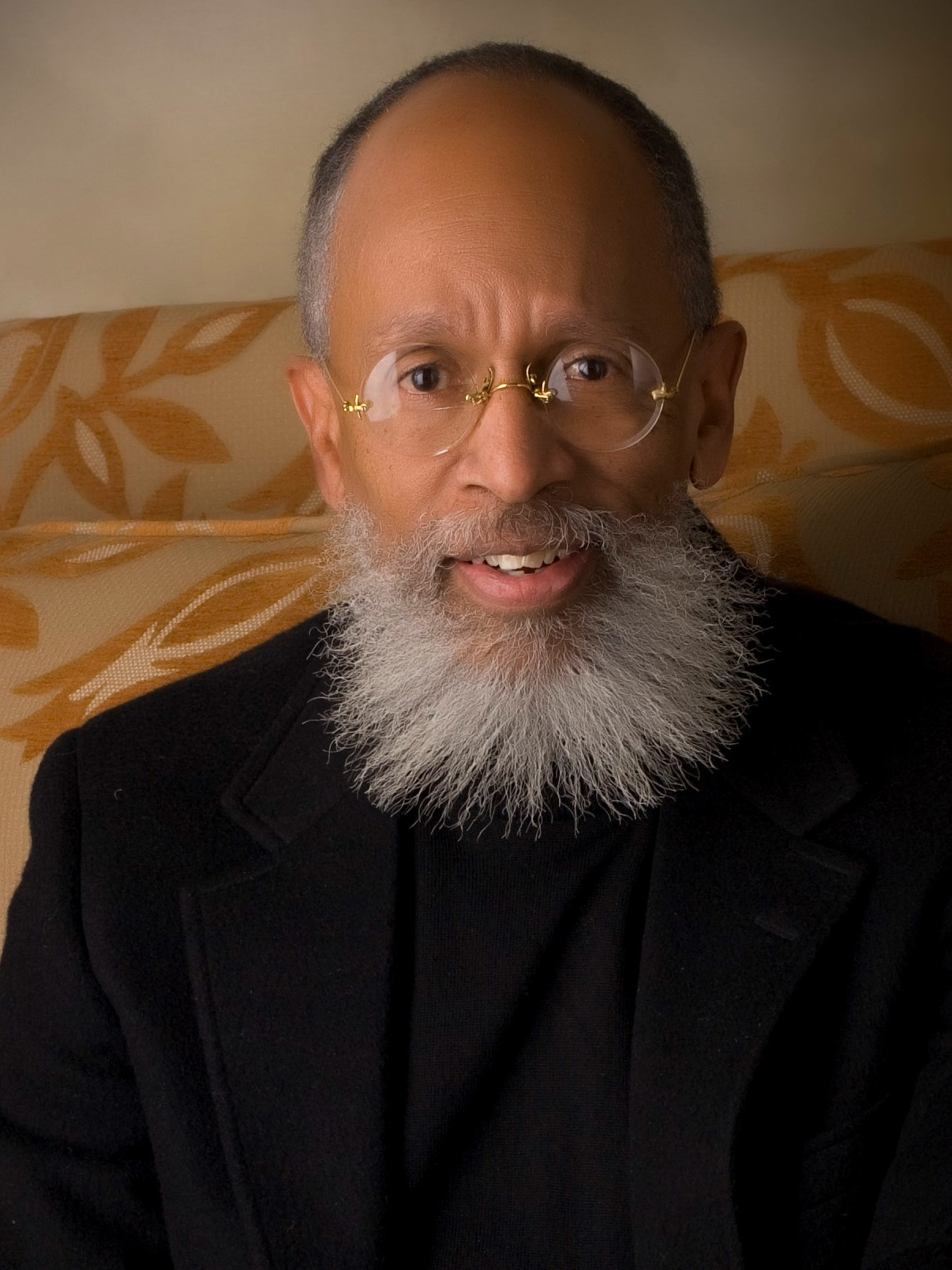

Enter King Davis, PhD’72, the Robert Lee Sutherland Endowed Chair in Mental Health and Social Policy at the University of Texas at Austin. An established leader in the field of behavioral health, Davis knew the importance of preserving these records better than most.

“This was the first institution in the world for African Americans with mental illness problems,” says Davis, who recognized how crucial this data would be for both historians and present-day behavioral health researchers focused on marginalized populations. “It would be tragic to allow their records to be destroyed.”

So Davis got to work, launching an initiative to preserve all of the hospital’s documents. But the challenges were daunting. Beyond the sheer scope of the project, Davis would have to strike a delicate balance between making the material accessible and upholding the privacy standards that come with any medical information. Not to mention, at the time, Davis was far from an archives expert.

He decided to assemble a team of professors, doctoral students, archivists, anthropologists and computer engineers, leading them on a decade-long effort to digitize the hospital’s records. Fortunately, large-scale interdisciplinary rescue projects like this were exactly what Davis had been preparing for throughout his career.

“Aside from his brilliant scholarship, Dr. Davis is a phenomenal weaver of connections,” says Vanessa Jackson, a social worker, state hospital researcher and writer whose research on African American psychiatric history has benefited from Davis’ efforts. “He has the ability to bring amazing thinkers together to work on solutions.”

Davis’ early career took a major turn when he was a graduate student working in a California state psychiatric hospital in the 1960s and got the call to join the Army during the Vietnam War. Davis entered the service as a second lieutenant and became the chief of social work at the Walson Army Hospital in Fort Dix, New Jersey, a first stop for many injured soldiers returning home from battle.

“I worked with hundreds of wounded soldiers and many grieved families who didn’t anticipate that their son was going to come back napalmed or with his legs blown off,” he recalls. “It was really traumatic.”

It was also highly educational. Just six weeks after finishing a master’s degree in social work from Fresno State University, Davis was hired to manage a hospital social work wing of 30 staff members. “The Army taught me a lot about taking risks and being willing to learn on the job,” he says.

After four years in that role, Davis decided to follow the path of his commanding officer, Joseph Bevilacqua, PhD’67, who had earned a doctorate at Heller and urged Davis to do the same. “Because he had gone to Heller, he told me all about the environment — what it would mean, how it fit well with my knowledge base and my career, and could speak to the quality of my life,” Davis says.

At Heller, Davis studied African American fundraising, focusing his dissertation on the United Way’s insufficient support for black organizations and alternatives that might better support African Americans.

“Heller more than lived up to my expectations,” Davis says. “Dean [Charles] Schottland was this extraordinary, bright, knowledgeable person. He gave me access to file cabinets filled with Social Security information — letters and policy documents — because he had been Social Security’s chief administrator. He also introduced me to people at Harvard and MIT and people in the community that I could work with on my dissertation. It was amazing.”

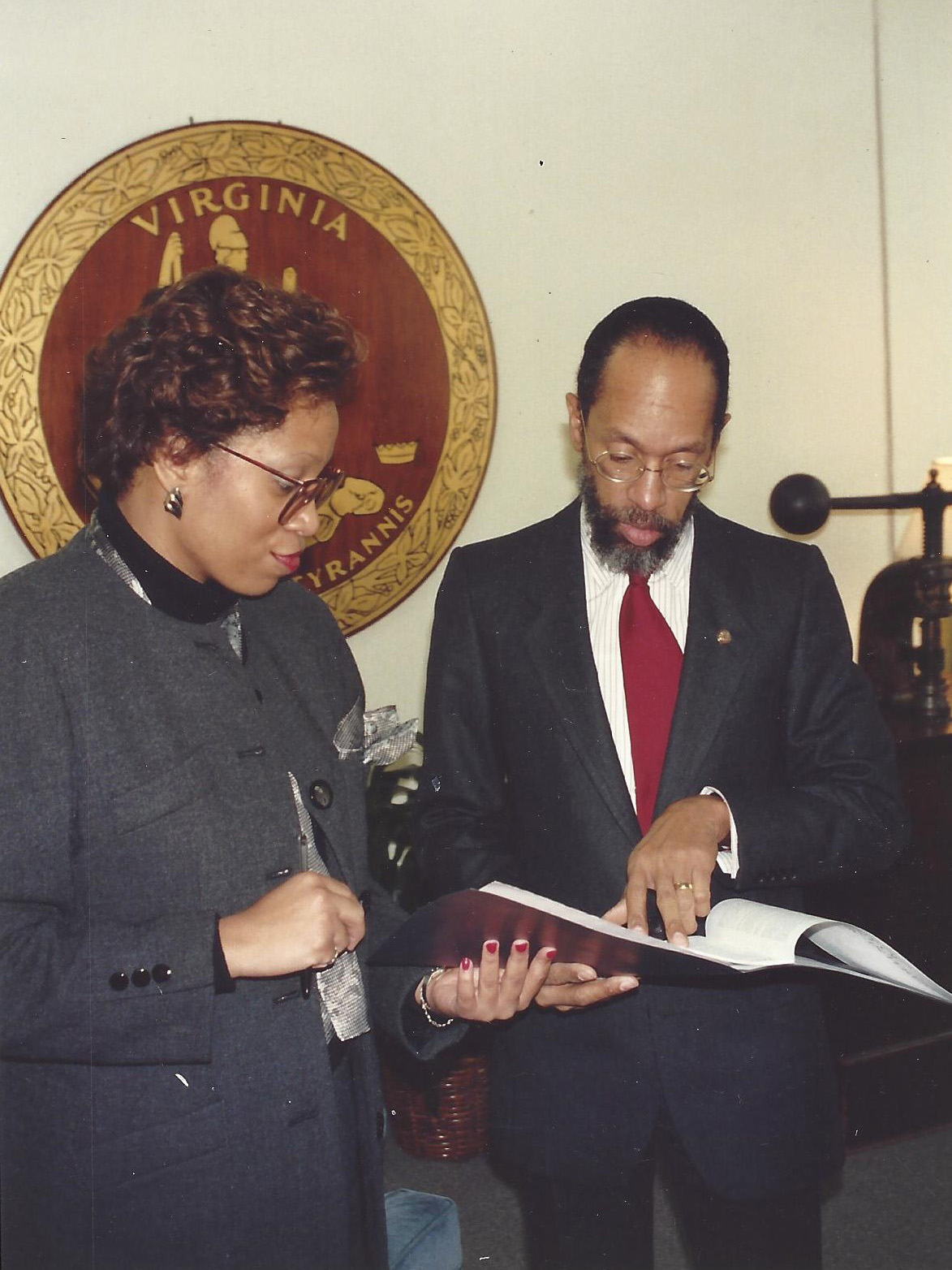

PhD in hand, Davis followed Bevilacqua to Virginia, where his former Army buddy was deputy commissioner of the state’s mental health system. Davis took a position as Virginia’s director of community mental health centers, overseeing 40 centers as the first African American in the department’s history — an experience he describes as a “bath of fire.” Virginia was then facing one of its most dire financial crises, with budgets being slashed by up to 15%. But Davis led a successful effort to transform community services, and through the challenge, he discovered his calling — balancing research and teaching with rescuing distressed public programs worth saving.

“That experience changed the way that I thought about my career,” he explains. “It convinced me that every few years I wanted to transition from being an academic to being an administrator of some program that was in jeopardy. ... I found that this was the best way to promote change. Academic work provided me with knowledge and skills that I could try out in various administrative positions. But I also learned that not everything taught in academia works or has real-world applications.”

From there, Davis carved out a nimble career, becoming the first African American commissioner of the Virginia Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services and leading university-based think tanks like the Institute for Urban Policy Research & Analysis at the University of Texas. He’s also transformed organizations such as the Hogg Foundation, which focuses on helping communities across Texas tackle mental health. Along the way, his work across the spectrum — including publishing numerous articles, books and reports on mental health, race and social justice — has earned him the University of Texas’ Excellence in Teaching Award and inspired the American College of Mental Health Administration to name its annual leadership award after him.

“Dr. Davis is always collaborative, willing to give of himself and always a font of new insights,” says William Lawson, professor emeritus of psychiatry at UT Austin’s Dell Medical School, who has worked with Davis for decades on issues related to African American mental health care. “Coming from rural Virginia myself, I struggled with the history and sometimes frank racism. King continuously made omelets out of broken eggs, giving mental health in Texas and Virginia a new dignity and perspective.”

So when Davis learned about the dire condition of those records at Central State Hospital, he went straight to work.

At the University of Texas, he connected with Unmil Karadkar and Patricia Galloway, two professors with digital archives expertise in the university’s School of Information. They helped him assemble the team to digitize the more than 800,000 documents that had been in jeopardy. They coded the new database so that family members can access private data on ancestors while researchers can access less sensitive, but equally valuable, data, like annual reports documenting length of stay, diagnoses and involuntary commitment rates.

This 10-year effort, known as the Central State Hospital Archives Project (CSHAP), earned Davis the American Psychiatric Association’s 2019 Benjamin Rush Award, which recognizes outstanding contributions to the history of psychiatry. More important, the digitization initiative has preserved and unlocked a crucial chapter in mental health history.

“I was wowed by his vision, tenacity and determination to preserve a resource most never knew existed,” says Earl Lewis, president emeritus of the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, which provided funding to complete the project. “Growing up in the Norfolk area of Virginia, I had firsthand knowledge of the facility. In the late 1960s, my maternal uncle had been a patient there. Furthermore, as a social historian, I knew how rare it was to gain access to the world of black mental illness. … I think that King’s colleagues at the APA understand how rare it is to be able to peer into the past in such a way as to better understand the present.”

Today, files from the project shed light on predictable but troubling truths. Some patients, for instance, were admitted simply for being in a neighborhood where they were unwelcome, talking back to a police officer or being insubordinate to an employer. But the data also promise to help contemporary mental health professionals improve diagnoses and treatments for minorities.

One key insight, for example, highlights how the disconnect between African American churches and psychiatric professionals can exacerbate mental health problems. CSHAP records indicate that African American populations have routinely delayed mental health care in part because they rely on pastors and other religious leaders for counseling.

“What’s missing is the connectedness between the black church and the formal mental health system,” says Davis. “We need to be able to find ways to bridge that.”

The project has also led Davis to advocate for a national policy for managing state historical psychiatric records and urge professional schools to focus more on the social and cultural context of mental health in the African American community. The findings clearly showed that since the 1800s, African Americans have been overdiagnosed and misdiagnosed with severe mental illness, but what’s even more notable is how the historical records aligned with more recent information.

“The most disturbing finding in our 10-year study is how similar our 19th-century data are to recent 2018 and 2019 meta-analyses,” says Davis, noting that much work still remains to be done to increase the understanding of mental health among African Americans.

Though receiving the Rush Award and delivering a lecture on CSHAP at the APA’s annual meeting in San Francisco may seem like the perfect capstone, Davis’ professional life continues to evolve. After a nearly five-decade career that intersected very little with digital archives work, his experience with CHSAP unlocked a new area of interest, leading him to join the School of Information as a research professor.

“Dr. Davis walks with power, humility, delight and profound curiosity, and he invites others to believe in our capacity to change society for the better,” says Jackson, who is one of many researchers who has benefited from Davis’ efforts. “His work has the potential, if heeded, to help transform the field of psychiatry into a potent force for healing, grounded in an understanding of the oppression inherent in the field and the possibilities for doing better.”