By Karen Shih

The political, military and religious leadership of a country ravaged by genocide and civil war. A cohort full of idealistic students nearing the end of their first semester in graduate school.

What could the two groups possibly have in common?

A complex, thought-provoking simulated society exercise that’s half a century old, says Alain Lempereur, director of the MA in Conflict Resolution and Coexistence Program (COEX) at the Heller School and an internationally-known negotiation expert.

“I don’t know any society where you don’t have people at the bottom of the ladder and leaders at the top,” he says. This exercise “brings us back to the reality of these inequalities.”

Called SIMSOC, the simulation can temporarily render the powerful powerless and turn the most progressive minds to self-preservation.

“This tool is anchored in sociology,” says Lempereur. “Negotiation often overemphasizes individuals’ free will and psychology. SIMSOC shows that people’s behaviors are also determined by where they start—whether they are rich or poor, which impacts the way they negotiate.”

In SIMSOC, participants are split into four groups, roughly representing different economic classes. They must find a way to work together to create a functional—even thriving—society where people are not only fed, but working productively to improve the economy and investing in public welfare and the environment.

Lempereur has taken the simulation around the world, and believes nearly everyone could benefit from the exercise, from children in elementary schools to leaders in Fortune 500 companies.

“The dream is to mainstream this kind of tool,” he says. “It creates awareness and empathy with others, and forces people to get creative in terms of finding solutions to work with the other side and act responsibly.”

What is SIMSOC?

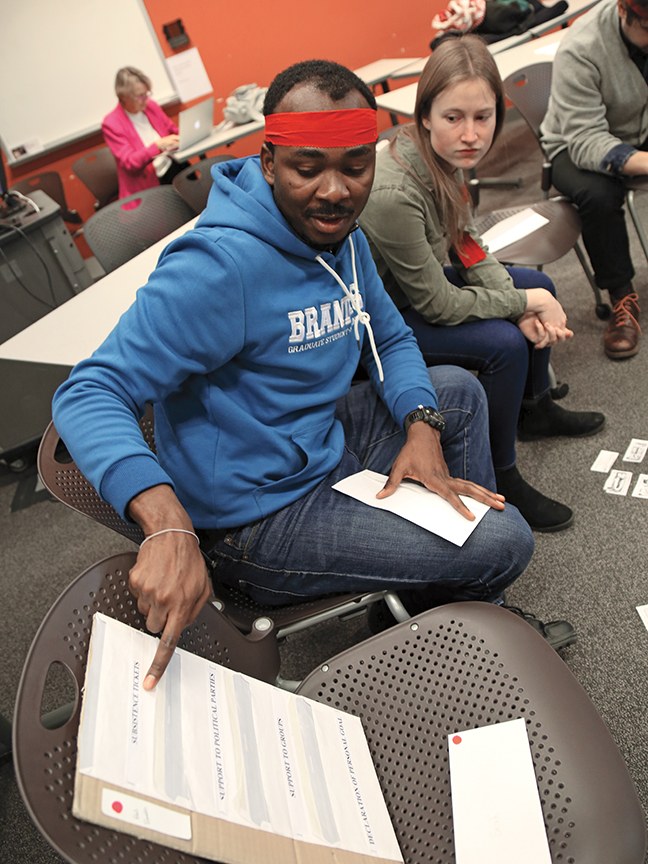

SIMSOC begins with a flurry of colors and acronyms, as participants are quickly given an overview of the rules before being dispatched to separate rooms to work within their regions.

Typically, the green region is the richest, with a high concentration of heads of society’s important institutions, like a political party, the mining industry, a non-governmental organization and the judiciary, as well as plentiful food tickets. (Every organization is given a nickname or acronym, like “MASMED” for mass media, “EMPIN” for the employees’ union or “BASIN” for basic industry.) The blue and yellow regions refer to the middle classes, with a few institutional leaders and some food tickets. The red region, the poorest, has no institutions, no food and no way to communicate with the other regions. Members of each region are deliberately sequestered, allowed only to interact with people from other groups if they have a travel pass.

Over three or four rounds, the region members must find a way to work together. The minimum requirement at the end of each round is for participants to have food, through a subsistence ticket, which can be obtained directly from someone who has one or through employment—otherwise, people eventually “die” within the exercise.

“Inevitably, some of you will do better than others in achieving your goals, but unlike some games, SIMSOC has no clear winners or losers,” writes SIMSOC creator William Gamson,* a professor of sociology at Boston College, in the rulebook’s introduction.

Even if one group successfully creates a productive industry and feeds and employs all its members, if the other regions are left behind for too many rounds, the whole society collapses—and the game ends.

Questioning Global Leaders

Since Burundi gained independence from Belgium in 1960, an estimated 400,000 people have been killed, another 800,000 forced to flee the country and tens of thousands more have been internally displaced, due to the Hutu-Tutsi ethnic conflict in the small, land-locked African country. In 2000, after years of negotiation, both groups signed the Arusha Accords, which signaled the possibility of a peaceful future under a new power-sharing agreement.

But warring parties have signed treaties all over the world—and many go right back to fighting “It can all fall apart in the implementation,” says Lempereur. “We knew that if we didn’t follow up top-level negotiations with leader training, it wouldn’t work.”

He was part of a team assembled by former U.S. Rep. Howard Wolpe to support the Burundi Leadership Training Program. From 2003 to 2007, they successfully trained more than 8,000 leaders through a series of retreats during that crucial time of transition. They had three major goals. One, to create unlikely meetings between former enemies that could build or rebuild relationships. Two, to provide frameworks and tools for more effective communication during the peace process. Three, to address the pressing problems of the moment, such as physical and administrative rebuilding of the country’s key structures.

Wolpe and Lempereur sought to reflect Burundian society in the trainings, working to include every political faction, people from far-flung provinces and the diaspora, as well as women and youth.

“SIMSOC was one of the cornerstones of these retreats,” says Lempereur, who was introduced to the simulation by Wolpe. “We would split the Hutu and Tutsi among the regions. And we’d put the rich and powerful—military leaders and bishops—in the poorest regions. For them, this was a moment of awareness: Whether you have power or not, you need to work on your contribution to society. Even if you have all the money and power, it’s all at risk if you don’t empower the most vulnerable. And if you’re the most vulnerable, violence isn’t the way to accomplish what you want.”

Lempereur and Wolpe later took their leadership retreats to the Democratic Republic of the Congo—which faced the same ethnic clashes, exacerbated by its larger size and greater natural resources—but found they didn’t have the same impact.

In Burundi, Lempereur was able to work with those at the highest levels of government, including the president and his Cabinet, as well as trainers in military and police academies, who could spread the concepts to a new generation. Their work reached a “critical mass,” while in the Congo, unfortunately, the retreats didn’t reach some leaders who needed it the most.

“High-level leaders are not questioned, and they’re not questioning themselves,” he says. “SIMSOC is a great questioning tool. We are never finished learning how we can do better.”

“Idealistic but Still Reactionary”

Take a group of Heller COEX students—many of whom have served in the Peace Corps, worked for NGOs and learned plenty about negotiation and peacebuilding during their classes—and drop them into SIMSOC. Surely, of all people, they’ll be able to create a functional simulated society, right?

“Heller students are among the most progressive crowds I’ve ever met with,” says Lempereur. “You can’t say these people don’t want to do good. But they fall into the same trap.”

Those on the green region, for example, become patronizing as they decide how to distribute resources, while those in the poor red region become frustrated and angry with the lack of communication.

He’s been doing SIMSOC with his COEX students at the end of their first semester since he came to Heller in 2011, calling it an effective way to pull together everything they’ve learned.

Some cohorts are more successful than others. Last year’s students benefitted from a tech wizard who wrote a program to dramatically boost the productivity of one of the industries, spreading riches throughout their society. This year’s students neglected economic development in favor of distributing food aid directly, leading to the first societal collapse Lempereur had seen in his 14 years of using the exercise.

But no matter the outcome, it’s a chance to learn essential lessons without any risk to real people in conflict areas, before the students take their skills into the real world. After a long, tense day in December 2017, students reflected on their experiences.

The simulation reinforced “the importance of the media to shed light on problems we didn’t know were happening,” said Isaac Cudjoe, MA COEX’18. With limited travel tickets, most participants relied on communication from the game’s designated head of mass media (who could visit any group at any time) or reports from their own region members to figure out what was happening down the hall.

“I realized how powerful it is to travel to other regions and see what is on the ground in other areas,” said Kate Fahey, MA COEX’19.

Because of the haphazard nature of travel and communication, participants’ intentions were often lost. “Paranoia runs high in this game,” said Lempereur.

The situation became particularly fraught between the green and the red regions.

“We came with a human approach to give you jobs and food. You just needed to sign up for our political party and NGO,” said green region member Hauke Ziessler, MA COEX’18, to the red region. “But the moment I entered your room everyone tried the grab the food tickets. Later, when we found out only one person signed up for the NGO, we thought you guys had stabbed us in the back and made a deal with someone else.”

Every group succumbed to regionalism, prioritizing the immediate needs of their members to the long-term prosperity of the society.

“SIMSOC showed us how hard it is to change systems,” said Marine Ragueneau, MA COEX’18. “We were idealistic but still reactionary when we had the chance to create our own society. It’s discouraging but invigorating.”

A Global Teaching Tool

From the Gaza Strip to primary school classrooms in France, Lempereur believes SIMSOC can help create lasting change.

“People want to know about these methods,” he says. “Let’s give them tools to negotiate a better way out of a situation that can incorporate social development and political cohesion.”

The simulation has a visceral effect on national leaders who can immediately connect it to their current context, forcing them to rethink how they treat those in need or how they react to violence in underserved communities. But Lempereur believes SIMSOC, through nonviolence and coexistence tools, could do even more good if people learned its principles earlier. He has advocated for it to be part of the French school curriculum, and he’s used it with undergraduate and graduate students, hoping it will inspire the next generation to build bridges and create equitable societies.

Many of his former students still email him, years after they graduate, about how they’re applying what they learned in the simulation to their work.

Ultimately, the main question of SIMSOC is: “Can you reconcile self-interest with the interest of everyone?” says Lempereur. “For overall social change to work, it’s not enough to have great leaders at the top. Change must come from all key actors throughout society.”

-

Note: SIMSOC was created by William A. Gamson with the first edition of the Manuals published in 1965 by The Free Press. With revisions included after each edition, the fifth edition was published by Simon & Schuster in 2000.