The Big Question

In 2007, as George W. Bush was wrapping up his second term as president and the economy began to careen toward the crash of 2008, journalist and professor Robert Kuttner started pondering a frightening question: Will unchecked global capitalism continue to skew income inequality and economic opportunity to such a degree that it undermines democracy itself?

“My lifetime project as an intellectual,” Kuttner says, “is to figure out how you marry an efficient economy to a socially just society to a strong democracy.”

He had begun working on a book — at the time, his eighth — on the question of global capitalism and democracy, then set the project aside for several years to write three other volumes. “What finally caused me to move this book to the front burner is that some of the things I had been worrying about started coming true,” he says.

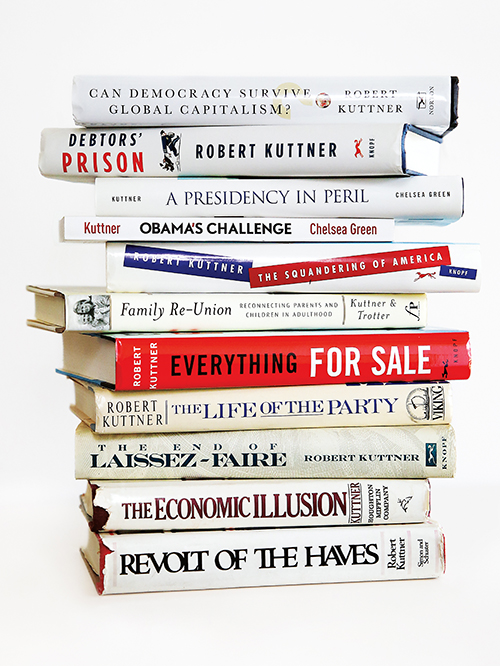

Over the years, as free market capitalism continued to surge, Kuttner saw the last vestiges of a socially just economy slip away. Far-right nationalist politicians began to gain power in countries once considered strongholds of Western democracy, such as Great Britain, France and Austria. By the time Donald Trump won the Republican nomination in July 2016, Kuttner put aside his other work to finish what he had started years before. “Can Democracy Survive Global Capitalism?,” his 11th book, was published in April.

The rise of President Trump and his political counterparts in Turkey, Hungary, the Philippines, Egypt and even Western Europe has fueled rampant speculation on the future of democracy. In Kuttner’s view, that conversation is incomplete without a thorough examination of free market capitalism.

“What you have is a double assault on democracy,” he says. “It’s being pummeled on both sides: first by global capitalism, and then by the reaction to global capitalism.”

The Fortress of Journalism

From an early age, Kuttner located himself at the intersection of political science and economics. “You really can’t understand politics without understanding power, and you can’t understand power without understanding economic power,” he explains.

With that in mind, he pursued training as a political economist. Kuttner graduated from Oberlin College with a degree in political science and spent a year abroad at the London School of Economics. From there he went to the University of California Berkeley, where he enrolled in a doctoral program in political science. “It was the chaos and tumult of the ’60s,” he says. “The civil rights movement, the anti-war movement, 1968, the Berkeley Free Speech Movement. The world was coming apart. I grew restless. So I took my master’s degree and ran to Washington.”

In Washington, D.C., young Kuttner got a job with I.F. Stone, whom he describes as “one of my absolute heroes.” Stone was an independent radical journalist and publisher of I.F. Stone’s Weekly, a popular newsletter among progressive circles. “I.F. Stone was kind of a blogger 50 years before blogging,” Kuttner muses. The position as Stone’s assistant was his first foray into journalism, and he was hooked.

Kuttner became a prolific writer, working at points in his career for The Village Voice, The Washington Post, Businessweek and The New Republic, as well as on assignments as a freelance journalist in radio, television and print. He published the first of his books, on the taxpayer revolt, in 1980. Other than a three-year stint on Capitol Hill as the chief investigator for Sen. William Proxmire’s banking committee, Kuttner has focused primarily on journalism, complemented by intellectual activism.

In 1986, Kuttner teamed up with friends who were dissatisfied with the imbalance of political think tanks in Washington. “There was the Brookings Institution,” Kuttner says, “which people thought was a liberal think tank, but it really wasn’t. Meanwhile, there was a proliferation of well-funded right-wing think tanks: the American Enterprise Institute, the Heritage Foundation, the Cato Institute, and so on.” Together, Kuttner’s group founded the Economic Policy Institute (EPI), which he calls the “first truly progressive economic think tank.”

A few years later, spurred by yet another Democratic loss in a presidential election when George H.W. Bush succeeded two-term President Ronald Reagan, Kuttner cofounded The American Prospect with health policy expert Paul Starr of Princeton and fellow political economist (and eventual Heller professor) Robert Reich.

“The conventional wisdom was that liberals hadn’t learned from the success of conservatives, and needed to become more like them,” says Kuttner. “I and a kindred group of people disagreed. We said the problem is that liberals had lost credibility with working people, the kind of people who put Roosevelt into office.”

The goal of the magazine is to put forward progressive ideas and connect policy to politics with in-depth explainer articles. “Mike Harrington, the great anti-poverty crusader, used to talk about the need for ‘politics on the left edge of the possible,’ and that’s us,” says Kuttner.

Today, Kuttner remains co-editor of The American Prospect, serves on the board of EPI, and continues to write regular opinion columns in the Huffington Post, and occasional pieces for The Boston Globe, The New York Times and The New York Review of Books. “When you publish an article that interprets something complicated to a larger audience in the form of narrative analysis, that has real people in it and that draws from different fields — that’s a real high,” he says. “I prefer my fortress to be journalism and make incursions into academia, rather than to have my fortress be academia and make incursions into journalism.”

Paying It Forward

Somehow, among his myriad responsibilities, Kuttner finds time to teach at Heller, where he’s been the Meyer and Ida Kirstein Visiting Professor in Social Planning and Administration for six years.

“Heller is the only public policy school I know of that advertises itself as a social justice graduate school. That means there’s a self-selection on the part of students: They’re not just here to get a credential, but to gain a deeper set of insights so that they can do social justice work more effectively. That’s what I love about teaching here,” he says. He teaches two courses per year: a module whose topic has varied, and his core semester class titled The Political Economy of the American Welfare State.

He brings the spirit of pragmatic idealism that drives The American Prospect into his teaching philosophy, pushing his students to consider not just the policies they want to see in the world but also the political feasibility of their ideas. “In three hours, my class could define a great set of policies that would carry out the welfare state in the United States. That’s the easy part. The hard part is figuring out who is going to support it, and how you’re going to get Congress on board, and how you get a broad public consensus behind your ideas,” he says.

Kuttner feels strongly that he owes a great deal to his roots in journalism and activism. “I’d like to think that each part of my career nourishes the other. The fact that I’ve been in the trenches, I think, makes me a more interesting and better-informed teacher, and the fact that I’m a teacher and a scholar creates some depth to my journalism.

“If there were more hours in the week, I would do more of all of it.”

A Phone Call From Steve Bannon

In August 2017, Kuttner and his wife, both fans of classical music, rented a home in the Berkshires for the Tanglewood music festival. It might have been the last place he’d expect to get an email from Steve Bannon’s assistant with an invitation to the White House. It turned out that Bannon had read Kuttner’s recent piece on U.S.-China trade policy, and loved it.

Kuttner suggested a phone call instead, explaining he had very little in common with the White House chief strategist and that he was on vacation. Ten minutes later, the phone rang. Thirty-five minutes after that, Kuttner had the biggest scoop of his life.

“Bannon is a personally weird guy, a far-right white nationalist but also an economic nationalist and a populist. And he’s looking for allies wherever he can find them,” Kuttner says. Throughout the conversation, Bannon trashed his colleagues and his enemies in government, openly disagreed with the administration’s stance on North Korea, dismissed the far right as “irrelevant” and “clowns,” and explained he was using identity politics and racism to “crush” the Democrats.

“I had taken the trouble to record the call,” Kuttner says. “And about five minutes in, I realized he’d never bothered to say if any of this was off the record. The ground rules are, if a high government official calls you and doesn’t say it’s off the record, it’s on the record.”

Kuttner consulted with his colleagues and board chair at The American Prospect, and put out the story the next day. “Then the phone started ringing off the hook. Every network, every newspaper,” Kuttner says. He found a studio an hour away at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and stayed there all day doing interviews.

“I’d never experienced anything like this. Then, of course, 24 hours later, Bannon was fired.”

The funny thing, Kuttner notes, is “I’ve been doing this work for over 40 years, and people who may not have read my serious work all of the sudden know who I am because of some cheesy piece of luck that made me a celebrity for three days. It shows you how random life is sometimes.”

The Future of Democracy

As a journalist, Kuttner’s role in Steve Bannon’s downfall is a highlight — but it is more the product of luck than any strategic move to create systematic change. While “Make America Great Again” motivates Trump-style white supremacists and populists, Kuttner takes a much different view of our nation’s history.

“Can Democracy Survive Global Capitalism?” grounds itself in the historical patterns of the U.S. political economy. For a unique three-decade period after World War II, the West, led by the United States, enjoyed an era of efficient, managed capitalism that delivered broad prosperity and reinforced democracy. That achievement, Kuttner argues, was undone by a restoration of elite power using globalization as the instrument.

“I think the most alarming echo is the 1920s,” Kuttner says. “When you have a prolonged period of time where the economic security and living standards of ordinary people drop, dictators gain credibility and democracy loses credibility. That was the story in Nazi Germany and other countries in Europe, and it led to war.”

If the 2018 and 2020 elections break the trend of rightwing nationalism, Kuttner says, there may be an option to avert disaster. Even so, he views a Roosevelt-style recovery as a long shot. “In the 1940s, the stars were in alignment. We had a government with an immense amount of prestige from having cured the Depression and won the war. We had a public willingness to have very high progressive taxes. We had an administration that was willing to put tight regulation on finance. And people believed in the government. None of that’s true right now.”

Still, Kuttner refuses to leave it at that. He’s already writing a sequel on what it will take to redeem a strong democracy. When asked if he’s an optimist or a pessimist, he quotes the Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci: “Pessimism of the mind, optimism of the will.”

Meaning, “Based on what you know, you have to be a pessimist. But based on your hopes and dreams, you have to be an optimist. I like to translate that a little differently. I see it as ‘pessimism of the mind, optimism of the heart.’ I think if I have a credo, that’s my credo.”