By Bethany Romano, MBA’17

In the winter and spring of 1979, when most of his friends were in their senior year of high school in his hometown of Greeley, Colorado, 17-year-old David Weil was a thousand miles from home, loading food and supplies into trucks in California’s Imperial Valley. He had dropped out of high school and taken a job with the National Farm Workers Ministry to support the United Farm Workers, who were on strike to promote fair labor practices.

He’s slow to bring it up in our interview, but it’s clear that this experience impacted him greatly. The United Farm Workers, a labor union cofounded by activists Dolores Huerta and César Chávez, organized thousands of mostly migrant Latino farm workers to strike and bargain for fair wages and better working conditions from the 1960s to the 1980s. The unjust violation of these fundamental rights was a deeply compelling cause to young Weil.

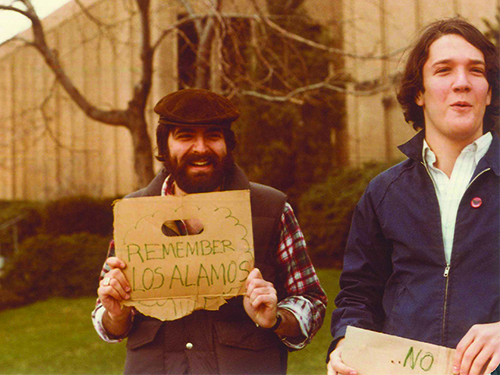

As a high school student, “I was a bit of a firebrand,” he admits, somewhat sheepishly. “Really, I was a handful. I wanted to get out of this little agricultural town I had grown up in, and there was always discussion about social issues and social policy at our kitchen table growing up. So I ended up loading trucks in southern California for six months.”

Those kitchen table conversations shaped Weil’s worldview. He speaks with great admiration about his father, a Jewish refugee from Nazi Germany, and his mother, the daughter of immigrants who fled Russia to work in New York City’s Lower East Side garment industry. “When we were young, my parents certainly represented a good chunk of the Democrats living in that part of Colorado,” Weil notes. “And my sisters and I were often the only Jewish kids in school. It’s always left a deep impression on me that this country offered my family a place to come to when they needed it most.”

Weil’s adolescent experience at the Imperial Valley farm workers’ strike brought the social justice ideals of his upbringing to the fore. “The work I did in California made it real,” he says. After the strike, he took a high school equivalency exam, got accepted to UCLA and later transferred to Cornell’s Industrial Labor Relations program, where he became interested in economics. After that, Harvard—first for a master’s degree, then a doctorate.

“My grandmother always predicted that I would be a professor, and I’d get so annoyed with that. I’d say, ‘no, professors don’t do anything, they just sit in their offices.’ But I was wrong about that, and she had me pegged,” he says, shaking his head and grinning. Weil says he’s always felt a tension between doing academic research for the sake of acquiring knowledge, and engaging with practical applications for “problems that really matter.”

Throughout his career he’s always come back to labor market and workplace issues and the industrial relations system. Weil built his career writing about and researching workplace policies. He is perhaps best known in labor policy circles for his work on the growing trend among companies to subcontract, franchise and otherwise outsource their labor to ever-more distant workers, a phenomenon he terms “the fissured workplace” and explores deeply in a 2014 book of the same name.

For example, a hotel chain may franchise its brand to individual hotel owners, who in turn contract a cleaning company to run the hotel’s housekeeping service. That service might then contract a laundering company to wash the linens. Since each actor in that chain takes a cut of the revenue from the original deal made with the hotel, there’s less and less money available to properly compensate workers. Furthermore, since the workers are often contract employees, they’re less likely to receive benefits, overtime pay or other protections.

The fissured workplace is contributing to ever-widening levels of inequality in the U.S., and its economic drivers often push employers to violate basic U.S. labor standards. Weil is interested in finding new ways to enforce labor laws that aren’t just reactive, but that root out the problem from its inception. In an ideal system, he believes, “We should prevent workers from experiencing wage theft or other abuses in the first place.”

For that reason, he says, “I always maintained an applied part of my research, whether it’s advising government agencies, like the Department of Labor, or doing mediation work,” he notes. For many years, he advised the Labor Department and other agencies on their enforcement strategies.

Then, out of the blue, a phone call from Washington, D.C.

“Someone I didn’t know, but who was working with the deputy secretary of labor, called me and asked, ‘Would you be interested in actually running this agency you’ve been studying?’ I thought it about if for about a millisecond, and said, ‘Well of course I would.’”

The agency in question was the Wage and Hour Division of the U.S. Department of Labor, which is charged with enforcing the United States’ most basic labor standards, including minimum wage, overtime pay and child labor laws. At the time that Weil was asked if he’d accept a nomination to be the agency’s administrator, the seat had been vacant for over a decade. Neither President Bush nor President Obama had managed to get an appointee through the grueling Senate confirmation process. Fortunately—despite taking an entire year, which Weil described as “tortuous,”—his appointment was confirmed in April 2014.

Leading the Wage and Hour Division gave Weil a more immediate view of the workplace policy problems he spent his career studying. “Millions of working people in this country are regularly deprived some of the most basic standards assured by our law. That was something I knew intellectually, but going around the country and actually seeing it, from the vantage point of our investigators and from the workers themselves—that was something else entirely. Meeting with employers was impactful too—some of them were flouting the law, and others were just struggling to meet those same legal requirements. It was such an eye-opener.”

For nearly three years, Weil led the nearly 2,000-member agency. Under his leadership, it began making more targeted investigations of employers in industries that are prone to violations. In 2016, the Wage and Hour Division also released a landmark new rule that would make millions of workers newly eligible for overtime pay. And throughout his tenure as administrator of the agency, Weil pushed to increase the diversity of his own workforce to match that of the populations they serve. His motto as agency administrator was direct: “A fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work.”

“That job gave me thicker skin,” laughs Weil, who left the agency at the end of President Obama’s second term in January 2017. It also taught him how to deal with very difficult policy decisions—and management decisions—in an environment with a wide array of stakeholder groups, both inside and outside the organization.

“That was invaluable to me, because it taught me new ways that you can bring a group of people together, look at very difficult problems, and come to a solution, together,” he adds. “That’s something that I certainly hope to bring to my role as the dean of Heller, but also in my work as a researcher.”

Like any distinguished researcher, Weil cares about rigorous analysis, though he regularly speaks about tempering the scientist’s itch for more data with the need to actually use data to take action. As the dean of Heller, he first intends to listen to and speak with all of the community’s different stakeholder groups. Then he wants to help bring Heller “to the next level.”

“There’s a ton for me to learn, there’s so much great stuff happening here, and I need to fully understand all of it. I believe in having an inclusive listening process and building a common vision of where Heller is and where it could go. But once we do that, I’m a big believer in actually moving, and really making things happen,” he says.

Of Weil, Brandeis Provost Lisa Lynch says, "As a former Heller dean, I hold a very special place in my heart for the school. I am thrilled that Dean Weil has been selected to lead the school in its next chapter, and I feel confident that his experience as an accomplished scholar, teacher and public official makes him an ideal fit for the job."

One of the issue areas where Weil feels Heller is ideally positioned to grow is inequality. “In a 2013 speech, President Obama described rising inequality as ‘the defining challenge of our time,’ and I think that’s exactly right,” he affirms. He goes on to point out that the U.S. is experiencing levels of inequality—across a variety of measures—unseen since the 1920s, just prior to the Great Depression.

“That’s a huge issue, and it’s not in any way a simple issue. It’s the result of multiple factors, and it manifests itself not just in wealth and income inequality, but in access to health care, differences in incarceration rates, opportunities to build skills in the labor markets, and the ability to retire with adequate savings—all of these factors, and many others, have been trending in the wrong direction for decades.” Between Heller’s 10 research centers and institutes, its seven academic degree programs and its rallying cry of “knowledge advancing social justice,” Weil believes the school is a natural convener for both national and international conversations on inequality and its solutions.

That means, in part, equipping Heller students with the skills and tools to engage with an issue like inequality: to analyze it, take it apart and examine it in a deep way. “That’s economic analysis, political science, sociology, organizational behavior,” he ticks off on his fingers. Those skills are important, he notes, but we then must decide what to do about the problem, and how to actually implement change.

“Very often, in public policy analysis, the desire is to have a bold policy solution. The danger is sometimes people don’t think a lot about how to make that happen. I learned in running the Wage and Hour Division: you have to think through those problems,” he stresses. “Great ideas stay great ideas if you don’t think about what it takes to implement them. Who are the stakeholders? How do you engage them? What are the obstacles that have thwarted dealing with the problem in the past, and how can you learn from that?“

After speaking with him for only an hour, it’s clear that Weil has high hopes—and high expectations—for Heller’s future. He speaks with great energy about the role Heller will continue to play in training the next generation of social change agents, and its potential to grow as a convener of research and advocacy around issues of social justice and inequality.

“I think Heller is a place that can uniquely bring people together to think about these issues, in creative ways and in impactful ways,” he urges. “When I had the opportunity to interview to be dean, I was really struck by this idea of ‘knowledge advancing social justice,’ and I found that in my discussions with faculty, students, alumni and staff, that it isn’t just words.”

This article originally appeared in the Winter 2017 issue of Heller Magazine.