By Tony Moore

This article appears in the Winter 2016 issue of Heller Magazine.

Let’s say you want to find out about the indigenous communities of Mexico, and you’ve narrowed your focus to those of Quintana Roo, a Mexican state located in what’s known as the Mayan zone. Quintana Roo, like the entire Mayan zone surrounding it, is known for its long and rich cultural history and its indigenous communities, people who have inhabited the region in small enclaves since the 10th century.

With this in mind, you might be surprised to see what your first Google search turns up: Photos of beaches lined with hotels and resorts, a landscape jammed with tourists sipping cocktails under beach umbrellas stuck in the sand like flags on the surface of the moon, establishing ownership. And then, as you lean in a little and take a good look at one of those photos, you catch a glimpse of someone from one of the indigenous communities you’re hoping to learn more about. Somewhere between the hotel and the pool, he’s frozen in time, delivering drinks to cabana 12.

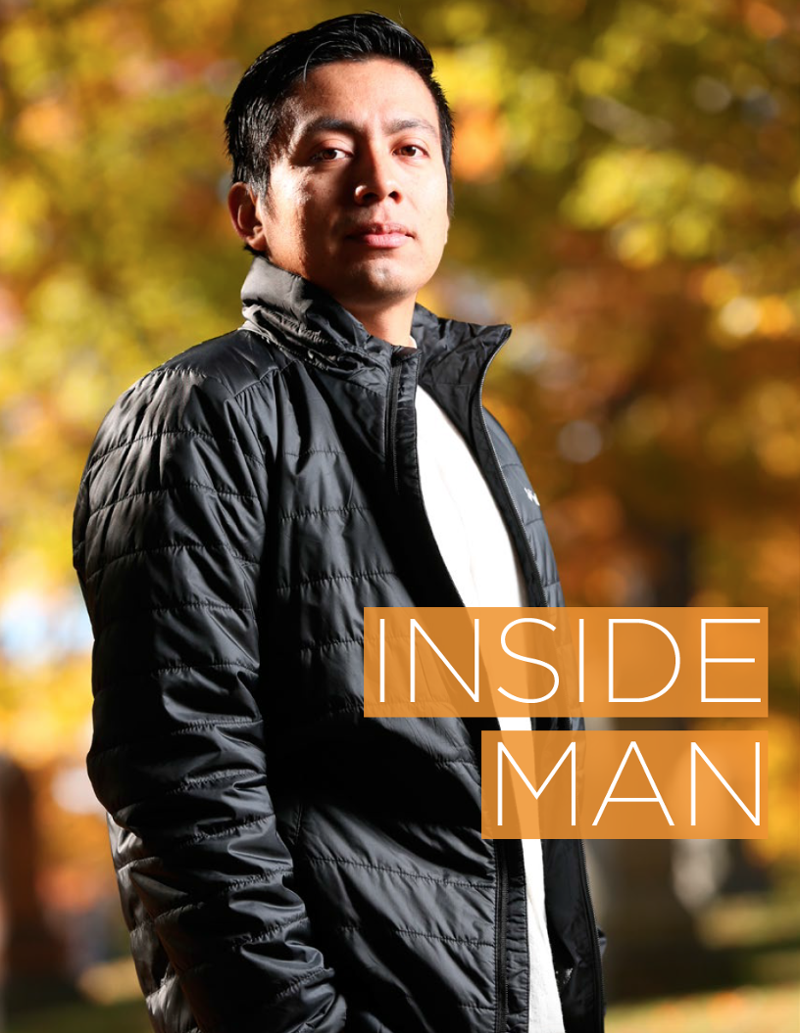

Like many communities in the Mayan zone, Quintana Roo has become a tourist destination, a place where those headed to Cancún or Cozumel only see indigenous people who have relocated to these resort towns for jobs. Briefly, right after graduating from high school, Edwin Pool, MA SID’17 was one of those people, working as a chef’s assistant on the Mayan Riviera. It was a life-changing experience, one he felt taking hold right away.

“I didn’t want to spend all my life working in a place where I felt like cheap labor,” says Pool, who grew up in a small community near Cancún. “I wasn’t a human but an object.” In response, Pool decided to go to college and explore his own language and culture, which he saw becoming overshadowed by tourism and the commercialization of the land he called home.

Change Agent

Indigenous peoples around the world—and there are more than 350 million of them in nearly 100 countries—face ongoing threats from a variety of outside forces: mining exploration, deforestation and the general expansion of other cultures at large, to name a few. In many areas of Mexico, the threat comes in the form of the ever-expanding world of tourism. And as Pool found out soon into his higher-education program, the situation was worse than he imagined: The language and culture he hoped to connect with were not just obscured, but slipping away, lost in an economic cascade that begins with a substandard educational system and ends at resort jobs that come and go, leading nowhere.

“And then I knew what I wanted to do with my life,” he says. “Stop recreating the same social pattern and be something else: a social and cultural change agent.”

Pool attended the Intercultural University Maya of Quintana Roo, where he worked with local people creating and implementing community development projects based on Mayan culture and language. Projects such as holding linguistic revitalization workshops and working toward the recovery and strengthening of a Maya ceremony called Ch'a'acháak (a rain petition ritual devoted to the Maya god Cháak) were driven both by Pool’s own need to connect with his heritage and the needs he saw in those communities.

“When I was a child I witnessed many Mayan rituals, and I loved them,” he says. “There was a full respect behind these rituals, a harmonic respect between humans and nature. But I did not want to create and implement a project by force. I saw how many governmental projects had failed by not taking into consideration the people’s necessities.”

Complex Elements, Intertwined

After graduating with a degree in language and culture, Pool worked for more than two years with Quintana Roo’s Department of Culture, where he designed cultural and artistic projects, implemented monitoring and evaluation tools and served as a liaison to the department’s federal government donors. And then he was off to graduate school, enrolling in Heller’s Sustainable International Development (SID) program, where he says he found what “sustainable development” was really all about—and crystallizes it for the uninitiated.

“I used to think that ‘sustainable’ was only about the environment and global warming,” Pool explains. “However, this term is very broad and complex, encompassing many other elements—such as inequality, gender, education, management, policies and rights—and these embrace other elements, making them even more complex.”

Pool—fully named Edwin Ivan Pool Moo, with both surnames deriving from Mayan words—says he fell in love with the SID program immediately and through it has been studying indigenous rights, Latin American regional development and technological innovations that can be deployed for development. With a concentration in environmental conservation, a field that can be applied to every corner of the world, Pool has immersed himself in the SID program’s rich global scope.

“The SID program is very holistic and approaches problems from different directions, integrating the newest policies, laws and management plans and constantly developing a curriculum that copes with these problems,” says Pool, now in his second year. “And this program is very international, with many students from Africa, Asia and America, including Latin America. Since I like to learn about other cultures and share my culture, this was an important fact that drew me as well.”

Pool’s love of SID is an extension of both his passion for and experience with the issues at the heart of sustainable development. He’s currently addressing those issues working with two organizations, Cultural Survival in Cambridge, Mass. and Yaax Chaak (Green Rain) in Quintana Roo, both dedicated to fighting for the rights of indigenous peoples in the face of development efforts that are often anything but sustainable.

“I’ve witnessed an interesting transition in Edwin’s identity through my Indigenous Peoples and Development class, when he reflected and then proudly accepted that he was not only Mayan but part of the indigenous peoples,” says associate professor Cristina Espinosa, Pool’s thesis advisor. “He is honest to the extreme and has a great sense of irony, which I see as one way he copes with the pain of injustice.”

Living, Feeling, Seeing

Pool says the one-two punch of his first and second semesters at Heller gave him the tools to tackle that injustice, while opening his mind to an international perspective he needed to absorb. After graduation, he’ll focus his efforts on working with international organizations, an approach that will allow him to see how global nonprofits operate and then appropriate their methods to transform local organizations from the inside.

“Edwin is deeply committed to defending indigenous culture while creating opportunities for economic growth and social advancement in his home state of Quintana Roo,” says SID program director Joan Dassin. “Based on this combination of passion for social change and Edwin’s newly acquired knowledge and skills, I’m confident he’ll play an important role in bringing social justice and economic opportunity to Mexico's indigenous communities.”

And those communities have always been where Pool’s head and heart are, where he came from and where he’s always set out to return.

“My next step will be to go back home and start doing projects and partner with local NGOs,” Pool says. “I live, feel, see and suffer problems that many of my people do. So I really want to make a positive change in my community. The SID program was created to change people’s lives for the better.”