By Sarah C. Baldwin

Harm reduction has been a primary focus of the Heller School’s Opioid Policy Research Collaborative (OPRC) since it was launched in 2017. Harm reduction refers to evidence-based, human-centered and stigma-reducing measures that are designed to protect the health of people who use drugs and their communities, such as overdose prevention sites, needle exchange programs and free naloxone kits.

In early December 2024, Traci C. Green, director of OPRC, and colleagues presented a report titled “Harm Reduction in the Commonwealth” at the Massachusetts Health Policy Forum. The report offered an analysis of various harm-reduction responses to the opioid overdose crisis. Among its 10 recommended strategies was the statewide authorization of community drug checking, enabled by testing technologies that reveal what is in an illicit substance. “Information about the drug supply is the single most important data point to calibrate our response to the opioid crisis,” the authors wrote, “yet it is virtually a black box.”

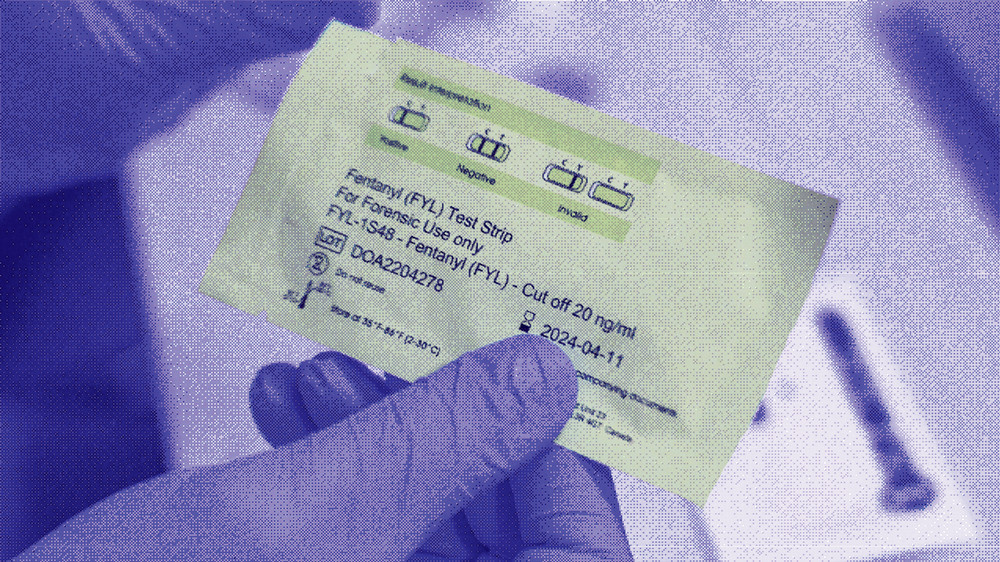

With additives like fentanyl and the animal tranquilizer xylazine, the composition of street drugs changes rapidly and, often, dangerously. Testing provides vital insight into the drug supply in a given area — data that are shared with the public — and enables individuals who use drugs to avoid risks, hospitalization or even death. Yet in many places, possession of products to test controlled substances has for decades been illegal.

Three weeks after the forum, on Christmas Eve, Massachusetts Gov. Maura Healey signed into law a bill that removes that barrier by providing blanket legal protection of public-health and harm-reduction personnel who perform drug checking — and, crucially, of individuals who seek drug checking themselves.

“Until now, legal protection was through local arrangements that were cobbled together,” Green says. “This bill enshrines those protections for our staff, the staff of our community partners and anyone in Massachusetts who’s worried about the drugs they’re using. It’s going to have a huge impact.”

Knowing what’s out there

Of the more than 105,000 people who died of a drug overdose in the U.S. in 2023, more than 2,125 of them were in Massachusetts. Then, in 2024, opioid-related deaths in the state declined by 36%. Green is currently scrutinizing the drug-supply data at the community level to better understand what’s driving that decrease. Policies that favor treatment-based approaches over legal-system responses have had a hugely beneficial effect, she says, but don’t account for such a steep drop in the mortality rate — the “flipping of the switch.” Knowing what’s in the drug supply might.

According to Green, “Community drug checking provides information to the person who is using drugs so they can have a safer experience. At the larger level, drug-checking programs gain a better sense of what’s happening in their community. Stepping back further, the state has a better sense of what the people in the Commonwealth need to be safe.”

Community partners are fundamental to the work

Green and her fellow researchers see their partners in the community — personnel at local drug-checking sites, whom they train and support, but also people who use and sell drugs, whom they consult — as fundamental to this work. “Monitoring the drug supply with our community partners means they see changes faster and can be more efficient in their response,” she says, adding, “Having a thoughtful state partnership means that investments and programming can happen, too.”

Community drug-checking programs also have a tool, created by OPRC with their input. StreetCheck (streetcheck.org) is a customizable app and website designed to streamline illicit drug sample collection, speed analysis and communicate easy-to-understand results.