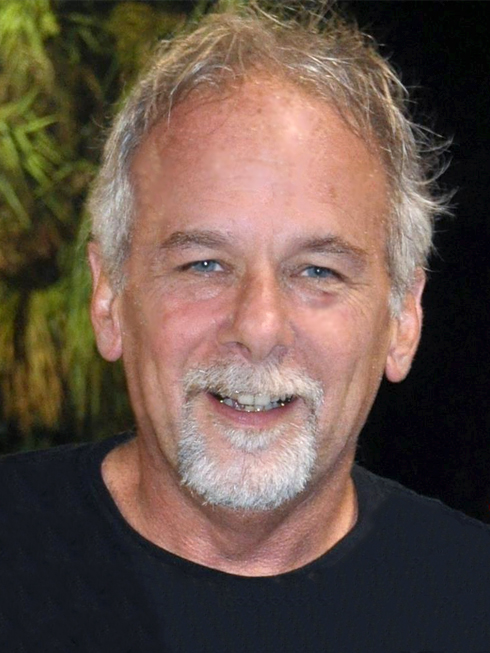

Bill Traynor, MMHS’84, is one of 15 alumni to receive a 2020 Florence G. Heller Alumni Award. He is a cofounder and partner at Trusted Space Partners in Lawrence, Massachusetts and has 30 years of experience in community development and as a community organizer. At Trusted Space Partners, Traynor facilitates grassroots change by strengthening relationships and building trust among local institutions, housing communities, and community-based organizations in Lawrence.

Earlier in his career, he helped to grow and lead the organizations Lawrence Community Works and Coalition for a Better Acre (CBA), Inc. Throughout his career he has also worked for national foundations and intermediaries, helping local grassroots organizations navigate issues of community organizing and community building. He was nominated and interviewed by friend and fellow award winner, Heather McMann, MBA’12.

Heather McMann: I nominated you for this award partially because of what I learned from you about community organizing and community building through your work at Lawrence Community Works, so thank you.

But let’s start with a big picture question: Throughout your career, would you say there's one big question or problem that you are trying to solve?

Bill Traynor: I think I've always tried to solve the problem of how to create environments where regular human beings can be their best selves with each other. What I mean by that is, to feel safe and to feel like things are fair enough so that you can relax and be generous and productive. So many of the rooms that we create are really not good for human beings: they’re dusty, badly lit rooms with bad food and bathrooms that are horrible.

We need to provide an environment where people are more willing to participate and lean in with their own agency, especially people that come from tough circumstances. It's not shocking that people don't come into these spaces and bring all their great energy to them because they're terrible spaces!

I think that was the hinge of going back to Lawrence and being part of Lawrence Community Works. I’m trying to bring a different way of thinking to that problem from the standpoint of, I would call it, network-centric or human-centric design and thinking. We need to bring more human-centric behavior and practice into those spaces. That's really the solution, but it's not easy to do it consistently and to do it well.

HM: How did attending the Heller School influence your thinking on this?

BT: I had never really picked up a calculator before going to the Heller School. I was a community organizer, an English and Sociology major in college, and as far as I knew, none of us knew what we were doing in terms of managing these organizations. That first summer at the Heller School was basically accounting boot camp.

It was not cool to be in the progressive circles that I was in, Marxist circles, and go to management school. That was an unusual choice and people looked at me differently because of that, but I went because I did want to learn how to manage these organizations.

The organization I was working for was going out of business. It was a powerhouse organization and so, I was like, “How does this happen? How does it happen that you lose this organization almost overnight?” I was motivated to learn what the “enemy” knew about how to run organizations.

I also realized that I'm a clarity junkie: I love to understand systems. I love to understand how things work, and a bunch of the classwork that I did, operations management, some of the other classes, were really eye-opening for me and really gave me something that I had been looking for, which is a way to understand with some logic model: What are we doing? How are we doing it? How can we tell if it's being done?

So, it was fascinating to me and it really gave me a deep curiosity with how we run these organizations. How do we think about community organizing as something that you can quantify and understand, build some predictability into and accountability into? It's become more common to have people with management backgrounds in those jobs now, but back then, not so much. I got a ton from Heller and it really changed my life in many ways.

And for the first 20 years probably of my career, I was running on: how do I create clarity in this murky world of nonprofits and community engagement? And how do I build organizations that really run well? It wasn't until later that I realized that wasn't enough—we can run these organizations well, but the practices were designed in the early part of the last century and they don't work anymore. That’s where a network-centric thinking came from. Now that we can run these organizations better, we can understand that they don't do the job they're supposed to do very well when it comes to engaging people in decision making and change and so on. We do it really poorly and we need a different way to think about how to do that. So that became phase two of my career.

HM: What advice do you have for Heller students today?

BT: I guess my advice is to get the skills. Lean into the stuff that you don't know. What I appreciated about Heller is it’s a better interface for people like us, whose goal is to do good things in the world.

I still use the accounting thinking that I learned at Heller in early July of 1982. And I think the logic models of thinking that allow you to break down a process, intentionally and automatically breaking that down into operations management parts. And that kind of thinking is so valuable.

I've spent a lot of time walking into an organization in New Orleans or Detroit or wherever and my job is: I need to size up that situation very quickly and understand all the dimensions, the programmatic dimensions, the management, the funding. I need to understand that person's life and their environment and without, I think, that deep immersion at Heller where I learned those systems and got that logic built into my head, it would be really hard to do that well. And I've seen it done poorly often enough to know the difference. There's a lot of people who do this work and they really don't do it well. So, if you're learning the skills, you can make a big difference.

HM: How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the work that you do?

BT: COVID has made me think a lot about the need to build an environment where people trust each other, and trust information. I do some work for the Federal Reserve Bank and a little while ago they brought in a guy that studies disasters and disaster response. And he said that the most important thing, especially at the beginning of a disaster, is trusted information. That's what you need, beyond water, food. If people don't trust information, they make bad decisions, and that makes a disaster worse.

With COVID, trusted information is the thing that we didn't have at the beginning. This network-centric way of thinking is really about building trusted spaces and trusted information so that more people can make a good decision in that moment, whether it's about their mortgage or their job or something that's happening in the neighborhood. With COVID, that stuff is needed so much more because the bad decisions that people are making are life-threatening decisions.

There are so many implications to people not trusting each other, not being willing to give up their health information to contact tracers, or to the people who manage their building. We need to be doing so much more of this trust-building work at the local level.

HM: What is your biggest career accomplishment?

BT: Well, it has to be going back to Lawrence and trying to create a different approach to the work in a real place with real people that I really cared about. I would say that the legacies of Lawrence Community Works and Coalition for a Better Acre are what I'm most proud of.

One of my big things is: strip away the delusions about what you think you know. All you really know is what's going to get you to the next set of choices that you will have. Staying close to the present moment, staying close to the moment of opportunity I think is a liberating way to be, it’s a liberating way to live, it's a liberating way to manage, it's a liberating way to have an organization act. I like that I've had the chance to explore that in real places with real people with real consequences and it hasn't been an intellectual exercise.