Residency Differences Between Fathers With and Without Disabilities in the United States

Samantha Shortall and Miriam Heyman · January 2024

Summary

This study examines the residential status of fathers by their disability status and explores whether paternal residency varies by different types of disability. Using the 2011–2019 National Survey of Family Growth, the study found that fathers with multiple disabilities were more likely to live apart from at least some of their children than nondisabled fathers when adjusting for socioeconomic covariates. There was a higher likelihood of living apart from children for fathers with cognitive and independent living disabilities. The findings highlight the importance of including disabled fathers in fatherhood programs.

Background

There are only a few studies focusing on the life and parenting experiences of fathers with disabilities. About 10% of adult men under 65 years old in the United States have a disability. Overall, paternal involvement in children’s lives is associated with positive child outcomes and improved paternal health. Past studies have shown strong associations between fathers’ co-residence with their children and positive developmental outcomes for children. Fathers of low socioeconomic status have a higher likelihood of living apart from their children due to a lack of financial and psychosocial resources. Disabled fathers face unique challenges jeopardizing parental rights because of their disability, and they also experience economic marginalization. Many fathers with disabilities do not receive enough parenting support or public services; these societal shortcomings may be associated with fathers’ residential status.

Findings

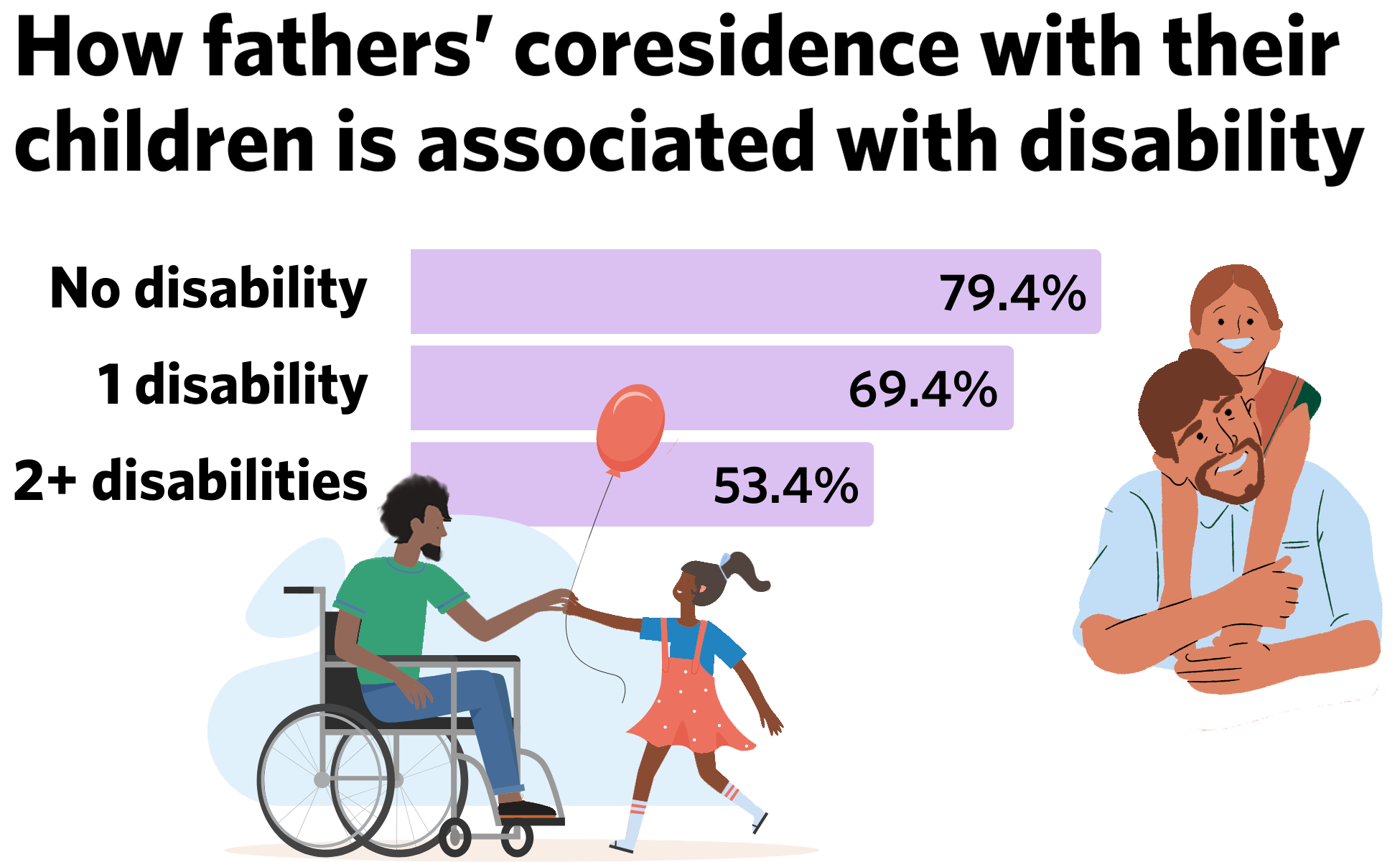

There were four major findings from the analyses. First, men with and without disabilities ages 15–44 are similarly likely to have a child aged 18 or younger. Second, disabled fathers were more likely to live apart from at least some of their children than nondisabled fathers—contributing to this disparity are higher rates of incarceration among men with disabilities. Almost four-fifths (79.4%) of fathers with no disability lived with all their children, compared to 69.4% of fathers with one disability and 53.4% of those with multiple disabilities.

Third, while many differences were no longer significant after adjusting for covariates, fathers with multiple disabilities had a higher likelihood of living apart from their children, even when adjusting for demographic and socioeconomic covariates. Finally, disparities persist after controlling for covariates for fathers with cognitive and independent living disabilities. This may be related to higher risk of incarceration and higher termination rates of parental rights among these disability groups.

Implications

There is still a gap in knowledge surrounding fathers with disabilities and their unique challenges and support needs, so further research is needed. It is important to provide social, financial, and community supports to enable fathers with disabilities to stay physically close to their children. It is also important to reduce the biases associated with disabled fathers in the criminal justice system and to provide supports to previously incarcerated disabled fathers. Further research needs to examine the factors contributing to non-residence status among disabled fathers, especially the effects of welfare laws penalizing disabled people for marrying and living with children, and the impact of discrimination and biased attitudes in the child welfare system. In addition, further research needs to investigate the differences in residential status by type and extent of disability.

Methods

This study used nationally representative data from the 2011–2019 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG). This study used a sample of 6,477 fathers ages 15 to 44 years in the United States, and this sample was based on a heteronormative perspective, assuming that each family would have one mother and one father. There were three categories of the men: no disability, one disability, and two or more disabilities. There was also a binary variable (no disability vs. any disability), as well binary variables (yes/no) for each of several types of disability. Finally, there was a residency variable. The study used Stata 16 for bivariate analyses and multinomial logistic regressions to examine differences in residency status.

Reference

Namkung, E. H., & Mitra, M. (2023). Residency differences between fathers with and without disabilities in the United States. Family Relations, 72(5), pp. 2917–2941. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12835