Parent-Centered Planning: A New Model for Working with Parents with Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities

Elizabeth Lightfoot and Sharyn DeZelar • March 2022

Introduction

Although people with intellectual and developmental disabilities—a broad category of conditions that includes autism, Down syndrome, and cerebral palsy, among others—are increasingly likely to become parents, formal services systems don’t yet acknowledge that reality. These systems typically focus on adults with developmental disabilities as individuals, rather than as parents or caregivers.

To address this gap, researchers have extended person-centered planning—a common approach in disability services—to support the needs of parents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Person-centered planning brings self-advocates and supporters together to determine long-term individual goals. Parent-Centered Planning does the same for people with disabilities and their children: parents with disabilities talk with family members and other supporters about the services, equipment, and support they need to raise their children successfully. Afterward, parents and their supporters create a formal plan that incorporates everyone's ideas.

Parent-Centered Planning Model

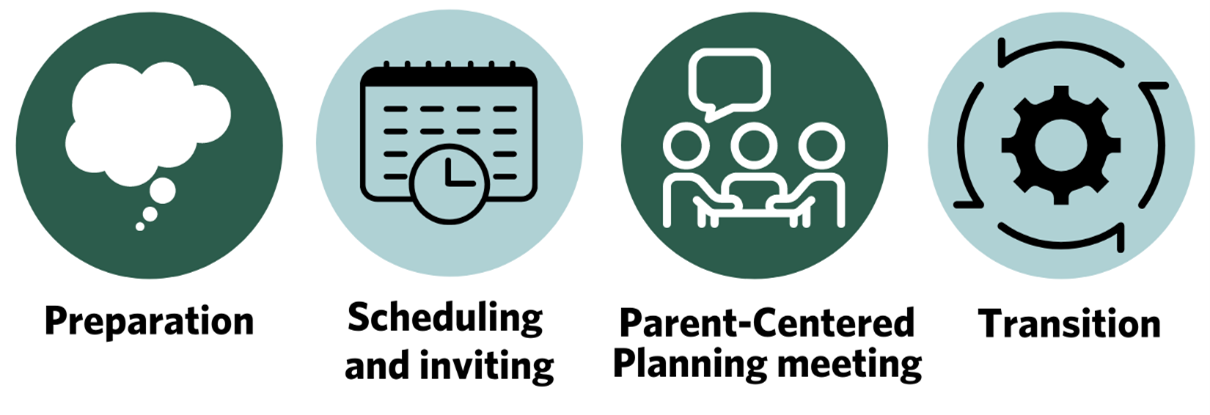

The Parent-Centered Planning model has four phases:

Phase One: Preparation

Parent-Centered Planning facilitators meet with parents—along with one or two close supporters if desired—to start working toward long-term goals.

At the preparation meeting, facilitators. . .

- explain Parent-Centered Planning and parental supports;

- help parents prepare for a Parent-Centered Planning meeting; and

- ask parents and their supporters to identify other supporters that they can invite to the meeting, using a simple relationship map to identify current and potential supporters from various contexts of parents’

Phase Two: Scheduling and inviting

Next, facilitators, parents, and supporters schedule the Parent-Centered Planning meeting and invite potential participants. Facilitators, parents, and supporters can all send invitations. Facilitators can also help. . .

- decide when and where to meet;

- ask parents whether they want their children to attend;

- explain to participants why they are meeting and how the meeting will work; and

- send reminders about the meeting.

Phase Three: Parent-Centered Planning meeting

Meetings are at the heart of the Parent-Centered Planning process. During the meeting, the facilitator uses a flowchart that helps parents break down complex goals into smaller steps. These steps include . . .

- identifying parents’ goals, dreams, and visions for their families—and any strengths or difficulties they’ve encountered as they raise their children;

- breaking down goals into attainable short-term goals for the next three to six months;

- identifying ways that supporters can help parents meet their goals; and

- determining whether parents need extra resources to fulfill their plans.

At the end of the meeting, parents and facilitators use the flowchart to develop a parenting support plan in which the participants commit to specific roles and actions.

Phase Four: Transition

In the transition or follow-up phase, facilitators meet two or three times over the next two months with parents and their supporters to help them complete the first steps of the plan. Facilitators work with parents to help them solve problems and break down steps into smaller tasks that may be easier to understand. In this phase, the goal isn’t for facilitators to perform any of the steps for parents or supporters, but to guide them in their decision-making.

Implications

The Parent-Centered Model is intended to improve the informal support that people with disabilities receive when they raise their children. Professionals who work with parents with IDD can use this model in a variety of contexts; for example, service providers or advocates could use the Parent-Centered Planning model to help a new parent get used to having a child, or to help people prepare for new stages in their children’s development. Child welfare professionals could use it with parents referred to the child protection system, too.

Only through further research, however, can we learn whether Parent-Centered Planning is feasible or effective, or whether it leads to better social supports for parents.

This information is intended to provide a brief summary of the model. For a more detailed description, please see:

Lightfoot, E., & DeZelar, S. (2020). Parent-Centered Planning: A new model for working with parents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Children and Youth Services Review, 114, 1-5.

Lightfoot, E., & DeZelar, S. (2020). Parent-Centered Planning for Parents with Disabilities. No. 36. Center for the Advanced Study of Child Welfare, School of Social Work, University of Minnesota. https://cascw.umn.edu/portfolio-items/parent-centered-planning-for-parents-with-disabilities-pn36/

Credit

Adapted by Finn Gardiner and Miriam Heyman, from Lightfoot, E. & DeZelar, S. (2021). Parent-centered planning: A new model for working with parents with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Children and Youth Services Review.

Disclaimer and Funding Statement

The contents of this brief were developed under a grant from the National Institute on Disability, Independent Living, and Rehabilitation Research (NIDILRR grant number 90DPGE0001). NIDILRR is a Center within the Administration for Community Living (ACL), Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). The contents of this brief do not necessarily represent the policy of NIDILRR, ACL, or HHS, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.