By Annie Harrison, Rabb MS’21

Chances are you’ve seen or used 3D printed gadgets – perhaps you’ve even printed one yourself. As Fab Labs and Makerspaces spread across the globe, more communities are gaining access to the technology and skills to design, create, and share more customized materials than ever before. There is even the potential for communities to become more self-sufficient – making what they need close to home.

At the Heller School, Social Impact MBA and Sustainable International Development students are gaining real job experience with these technologies, discovering ways that communities and companies can advance a more sustainable and inclusive future.

“It bridges the digital divide between nonprofits and underserved communities and people who use tech,” says Sazia Nowshin, MBA/MA SID’22.

From building inclusive spaces and open-source ecosystems to enhancing supply chain solutions and disaster relief, digital fabrication is shaping the future of social policy and business.

What Are Fab Labs?

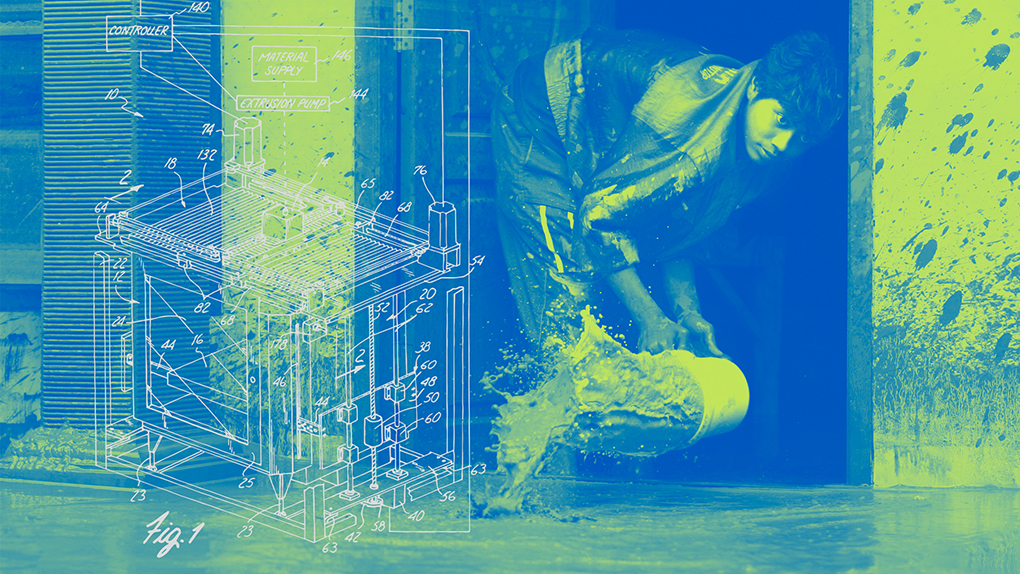

Fab Labs enable creators to bring their designs to life.

Often located in schools, libraries, or community centers, Fab Labs typically contain digital design and fabrication equipment such as 3D printers, 3D scanners, laser cutters, and other machines. They may also contain other creative equipment such as power tools and sewing machines. There are over 2,500 Fab Labs in the world and several thousand additional Makerspaces. The Fab Labs are connected through a global foundation, shared technology, and a connected community. The Makerspaces share many of the same values and technologies, but are not as tightly knit with each other.

Fab Labs began as part of the outreach component of MIT’s Center for Bits and Atoms (CBA). The first two Fab Labs were launched in rural India and the South End in Boston, both in 2002. The Boston Fab Lab was initiated by community leader Mel King and MIT professor Neil Gershenfeld, who is the brother of Heller Professor and Associate Dean for Academics, Joel Cutcher-Gershenfeld.

Cutcher-Gershenfeld and his eldest son regularly volunteered in the South End Fab Lab between 2003 and 2005 and then Joel helped launch a Fab Lab at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign in 2013.

“Heller students can learn from Fab Labs how to foster design thinking in a community, how to harness new technologies, and how to be more inclusive with technology,” he says. “We discuss Fab Labs in our curriculum as an example of decentralized, community-led forums that are shaping local and global ecosystems.”

Creating at Brandeis

Brandeis University has its own MakerLab, which was conceived to be at the intersection of a Fab Lab and a Makerspace. The Brandeis MakerLab emphasizes a social justice vision and broad access to innovation expertise and technologies.

Ian Roy ’05, director for Research Technology and Innovation at the Brandeis Library and the founding head of Brandeis MakerLab, explains that Heller students have collaborated with the MakerLab on several projects in recent years – especially around social entrepreneurship.

“The MakerLab has supported the Heller Startup Challenge for the last few years with Saturday Design Thinking sessions on early stage startup features. We facilitate a one-hour design session on ‘Knowing Where You Are and Knowing Where You Are Going’ for most of the teams on drilling down to what their essential, nice-to-have, and reach features are,” he says.

“We also do a fair amount of consulting on physical prototyping for early stage startups – or for market analysis of things that involve design or physical manufacturing.”

Roy says innovation requires both a fresh idea plus implementation to add new value to solving a problem. Implementation, or the ability to see things through, is the hardest step, he says, which Heller students are particularly good at recognizing.

“Heller School students have a global perspective that can help focus the toolsets of a makerspace for local impact,” he says. “The MakerLab at Brandeis has all these powerful design tools and innovation methodologies, and the students from Heller can help to see around corners for the next opportunity to apply them.”

Innovation and Inclusivity

As Fab Labs expand into more communities, these spaces are placing a greater emphasis on equity, inclusion, and diversity, Cutcher-Gershenfeld says. With Fab Labs in more than 100 countries, there is still a lot of work to be done to make sure the culture is welcoming and accessible for people regardless of race, gender, class, age, or physical ability.

“The conversation is about diversity on many dimensions,” he says. “Wherever you are, the goal is for Fab Labs to be exemplary and allow everyone to come together to learn and grow. Fab Lab leaders from around the world have now launched the Fab All-In curriculum, in which inclusive innovations are shared. A Fab Lab in Spain reported, for example, that their programming on robotics mostly brought in boys, but when the programming expanded to include the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals, more girls came in.”

When Nowshin was a student at Heller, she interned with Fab Foundation, an organization dedicated to expanding access to digital fabrication equipment and technology. During her internship, she analyzed diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives at Fab Labs around the world, identifying a plan to highlight “Fab Lab Champions” and their work, and authoring a series of case studies on the topic.

Nowshin, who recently started as a consultant with Capgemini, says Makerspaces and Fab Labs can be a wonderful way to increase diversity in STEM fields when the equipment is provided to the public for free and it is in an accessible location. She says when children have access to these types of facilities early on in their education, such as in public schools or libraries, they are more likely to continue pursuing STEM education and careers.

She adds that early education is key to increasing gender representation in STEM. Case studies show that when more female engineers come into schools to teach girls how to code, more female students then seek out Fab Lab and related programs.

“When you incorporate this into early education programming, that is when I think it is the most effective,” she says.

She references a case study from a Fab Lab in Chattanooga, Tenn., where the school got rid of remedial classes and instead implemented Fab Lab equipment and lessons in the curriculum. After working with the equipment for a few years, students had built strong technological skills to create their own digital fabrication agency.

“First you educate, then they innovate, and eventually they invent something of their own,” she says.

Community-Centered Manufacturing

Community is at the forefront of Fab Lab culture, Cutcher-Gershenfeld explains, and these spaces are playing an increasing role in local economies. He says Fab Labs have demonstrated in recent years the potential to help make communities more self-sufficient, improve digital literacy, and fill gaps in the supply chain. This is the focus of an article on “The Promise of Self-Sufficient Production” that he co-authored in 2021 with both of his brothers, Neil and Alan Gershenfeld, in the Sloan Management Review.

If it weren’t for her experience with the Fab Lab community, Isabella Kaplan, MBA/MA SID’21, doesn’t think she would be working on economic sustainability issues at the World Economic Forum.

Kaplan’s time at Heller fueled her passion for sustainable and community-centered business. Before graduation she also interned with e-NABLE, a community organization that creates free 3D-printed hands and arms for people in need of upper limb assistive devices. She assisted in strengthening coordination in e-NABLE’s decentralized ecosystem, streamlining the onboarding process and organizing information into an easily navigable website.

Fab Labs and Makerspaces should be accessible, and teach people how to use machines and customize products, Kaplan says. Introducing more people to new technologies will provide them valuable skills and allow them to access job opportunities in the manufacturing field.

“The distributed model of manufacturing that is possible with Fab Labs and Makerspaces lowers the barrier to entry for a lot of people, including people with disabilities or people with limited skill sets,” she says.

Kaplan explains that although the term “manufacturing” is often associated with big production, it can also refer to customization or smaller batches of items. When communities are able to manufacture and customize items for their own environment, such as creating their own clothing and devices, they are able to create more local jobs and opportunities for upscaling businesses.

As a platform coordinator with the World Economic Forum in Geneva, Switzerland, Kaplan now focuses on distributed manufacturing governance, meaning that instead of a top-down approach, smaller groups have decentralized autonomy. She explains that decentralized models – like those found in Fab Labs – are important for a number of reasons, especially in terms of sustainability.

“A distributed manufacturing model allows for use of local resources and less energy cost in the transportation of services in and out of a community,” she says.

Disaster Relief Solutions

This model of distributed manufacturing can be especially beneficial during times of disaster relief, Cutcher-Gershenfeld adds.

“There is a movement in the disaster response world called localization,” he explains. “Rather than bringing supplies in, can we build capacity? If you need 10,000 buckets, do you ship in 10,000 buckets, or do you help a local producer shift their focus to create the buckets?”

Cutcher-Gershenfeld acknowledges that there are challenges to this approach, such as ensuring Fab Labs have access to electricity and raw materials, but there are organizations that are working to make this a reality.

Centering community needs during times of crises is crucial to making sure people get materials that are best suited for their needs, Kaplan says.

“Sometimes the resources provided to the community are not best suited for the community,” she says. “So this model will provide tools, and people can customize it for what they need.”

Distributed manufacturing is not limited to Fab Labs or Makerspaces, Kaplan continues. More organizations are expressing interest in pursuing decentralized, community-led models of manufacturing, but aren’t sure how to proceed. Having localized hubs for manufacturing can make supply chains more resilient.

“I think a lot of organizations will be looking at Fab Labs as a model for the future,” she says.

Open-Source Ecosystem

Working with the Brandeis MakerLab and e-NABLE helped Ali Elliott, MBA/MA SID’22, shape her own social entrepreneurship endeavors.

“It’s like creative engineering – you need the technical, creative, and math skills,” she says. “It was interesting working with e-NABLE coming from a different background and being able to absorb what they are doing and share it with chapters all over the world through various events.”

e-NABLE is a distributed open-source community. Their members create designs to 3D print prosthetic arms and hands. The community volunteers their time and resources to make prosthetics for individuals in their communities. These assistive device designs are created and shared openly with the goal of making the information more accessible and equitable. As Elliott progressed through her program, she developed an appreciation for how open-source ecosystems provided students and other beginners with expert advice and community resources.

She took this approach back to her own company, Farmer Foodie, where she has published more than 200 free and accessible plant-forward recipes and promotes sustainable organic food.

Elliott said her experience in the Social Impact MBA program, combined with what she learned with the Brandeis MakerLab and e-NABLE, gave her the knowledge and skills to take her business to the next level. Through Farmer Foodie, Elliott launched her first dairy free cheese product, “Everything Cheeze,” shortly before graduation in May 2022. Everything Cheeze is a shelf-stable “cashew parm” made with fair trade organic cashews.

“In March 2022, I was in the Brandeis Innovation Spark program and I decided to pivot from a boxed vegan mac and cheese product to a line of cashew parm products free from dairy, gluten, and soy,” she says. “I went from an idea on March 10th to an actual product on May 17th."

The open-source approach to sharing information has inspired Elliott to continue to seek that community as an entrepreneur. She knows she can rely on the connections she built through Heller to continue learning from her peers as well as contribute her own expertise.

The Future Is Here

As for how makerspaces can play a role in creating more equitable and inclusive spaces in communities, Roy quotes science-fiction writer William Gibson: “The future is here. It’s just not evenly distributed.”

“Makerspaces can give a glimpse of a future of abundance where fully-realized humans can explore and create,” Roy says. “Just as someone once opened the door for us, it is our obligation as makers to empower others to reshape the world, and there are excitingly more and more models for mapping a Makerspace to the local culture of communities around the world – whatever their values are.”

Roy says the Brandeis MakerLab encourages people from all backgrounds to come together to develop solutions to complex problems, because the collective experiences of a team can help them see around corners and find new paths forward.

“In order to create the richest solution possible,” he says, “we want the artist sitting next to the business-person sitting next to the scientist – all colliding and seeing different aspects of the same problem and pointing that out to each other.”