By Karen Shih

For the most frequent emergency room patients, it isn’t enough to simply treat their immediate medical problems — health systems must look at the bigger picture, addressing any housing, food, legal or other social needs that could trigger constant readmission.

That’s the key takeaway from a new evaluation of the Lahey-Lowell Joint CHART Program at three Lahey hospitals. Scientist Mary Brolin, PhD’05, of the Institute for Behavioral Health (IBH) led the evaluation, which found that the program demonstrated a gross savings of $4.5 million over the two-year pilot period, or $5,122 per patient. This is largely the result of reduced hospitalizations, including both decreased hospital admissions and fewer days in the hospital — all good news for patients, too.

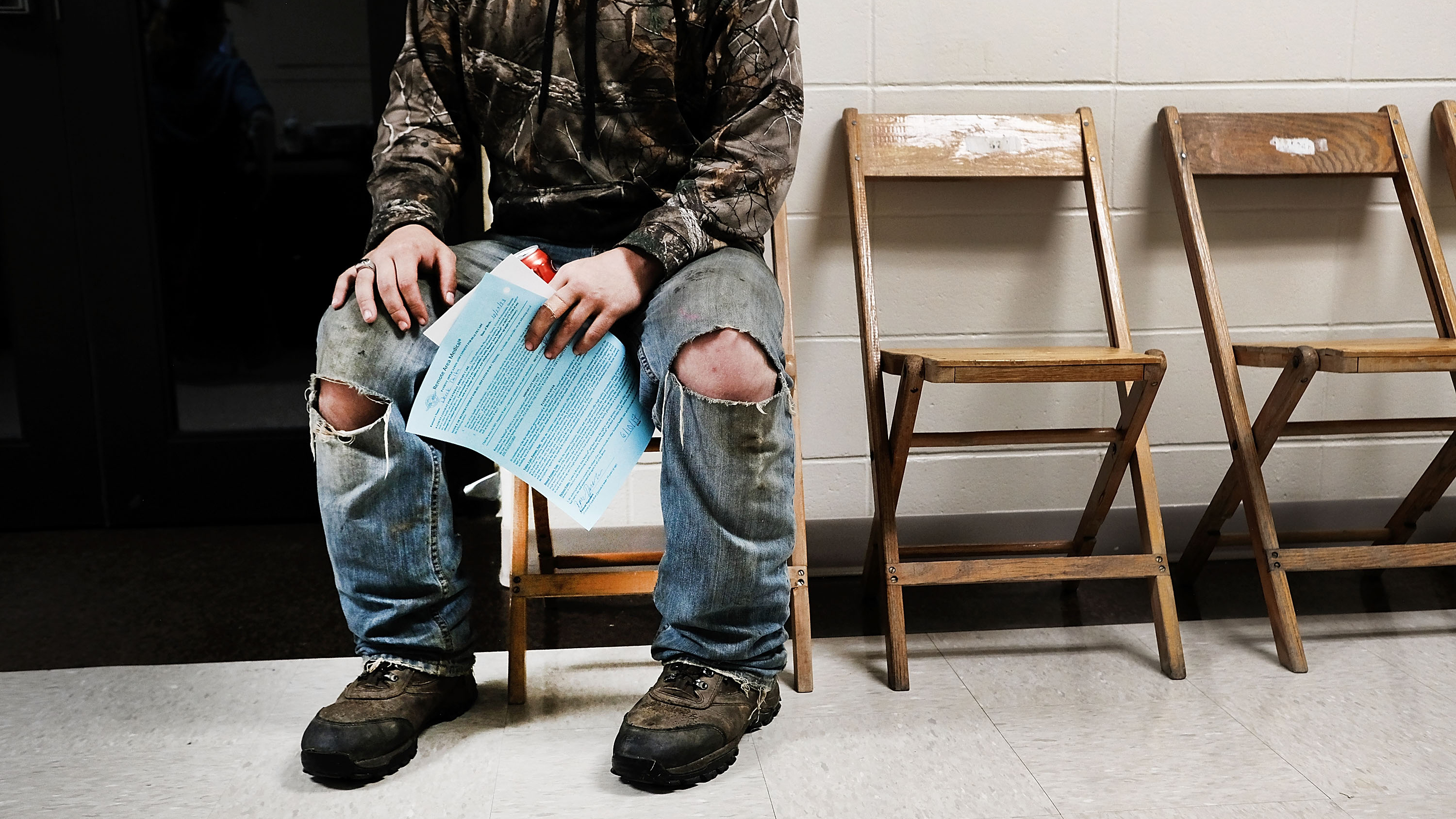

Brolin says, “Patients may come in with a broken arm or difficulty breathing, but if you talk to them, there are underlying issues: They may have mental health or substance use problems, or they may have a condition like diabetes and aren’t taking their medication properly. Social issues wrap around that: If you have unstable housing, you can’t work. It’s hard to stay healthy if you’re living outdoors. And food insecurity can exacerbate health issues.”

The CHART Phase 2 Program (Community Hospital Acceleration, Revitalization and Transformation Investment) was a two-year initiative funded by the Massachusetts Health Policy Commission from 2016-17 to improve health care delivery and reduce system costs at 25 locations across the state.

Lahey’s CHART program embedded community health workers at each hospital to work with patients who were admitted to the emergency room eight times or more over a 12-month period. In traditional medical care management, a nurse might provide a topdown clinical assessment, refer the patient to behavioral health services and discharge the patient. But through CHART, a social worker or community health worker partners with the patient on the assessment to address their needs and follows up regularly over six to 12 months to make sure the patient is accessing appropriate services in the community.

In addition to a quantitative analysis, Brolin and a team of IBH researchers also conducted qualitative interviews with CHART team members and key stakeholders, like emergency room staff, housing and social service organizations, and the police.

CHART staff highlighted three aspects of the program that made a difference. First, they transported clients to the services they needed, rather than simply making referrals. Second, they gained valuable information from home visits, such as lack of heat or food, that patients wouldn’t always share in a hospital environment. Third, they stressed the importance of having social service providers within the community — if they were too far away, patients wouldn’t use them.

Both inside and outside the hospital, CHART was a success. Emergency room staff valued the program because it allowed them to focus on medical care. In the community, CHART partnered with task forces that brought social services and police together, giving them an opportunity to work collaboratively to help their most vulnerable residents.

Ultimately, however, Lahey recognizes that although the CHART program is innovative, further interventions could be more disruptive and transformative, and is, therefore, pursuing additional pilot programs now that CHART is over.

“For real system transformation, we need bigger changes,” Brolin says. “Instead of dealing with a problem when someone is really sick, what can we do to prevent them from having that problem?”

The project described in this article was supported by a Community Hospital Acceleration, Revitalization and Transformation (CHART) Investment from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Health Policy Commission (HPC).